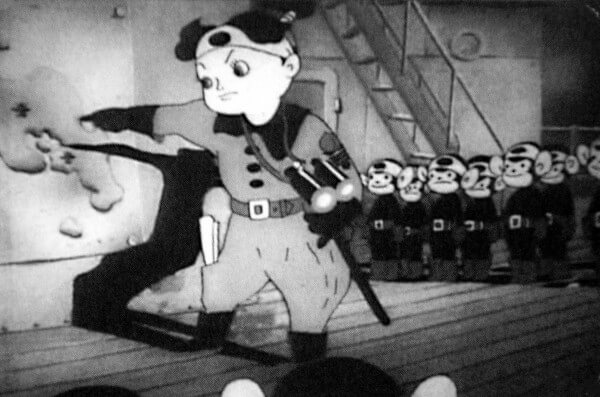

Yesterday, Funimation® Entertainment announced its acquisition of the restored edition of Mitsuyo Seo’s Momotaro, Sacred Sailors – the first feature-length animated film produced in Japan. Written and directed by Mitsuyo Seo (1911-2010), Momotaro, Sacred Sailors is a propaganda film that was produced in 1944 by Shochiku Co. Ltd. and released in 1945 during the final months of World War II. Earlier this year, Shochiku was able to restore the 74-minute, black and white film, with the financial support of Funimation and others. The restored film premiered during opening weekend of the 2016 Cannes Film Festival as part of the Cannes Classics program. Through its agreement with Shochiku, Funimation has secured exclusive rights to the theatrical, digital, and home video distribution of the film in both the U.S. and Canada.

“Mitsuyo Seo was a key figure in the development of Japan’s anime industry and we’re honored to have been part of the restoration of Momotaro, Sacred Sailors – one of his most famous works,” said Gen Fukunaga, CEO and founder of Funimation. “This wonderful black and white film was created using almost 50,000 cels and offers superb animation, music, and entertainment that is on par with any classic Disney film of the same era.”

“This digitally restored version of Mitsuyo Seo’s ‘Momotaro, Sacred Sailors’ is truly captivating,” said Mike DuBoise, EVP and COO of Funimation. “Anime fans, film buffs and animators alike will not want to miss this seminal and historic work of Japanese animation.”

Seo’s film is based on the classic Japanese tale of Momotaro, a boy who is born from the inside of a peach and goes off to vanquish monsters with the aid of animals he befriends along the way. In Seo’s movie, Momotaro and his friends are now Japanese naval paratroopers and the monsters represent the Allied Powers, reflecting the times and the desires of the Japanese government.

Backed by Japan’s Ministry of the Navy, Shochiku produced Momotaro, Sacred Sailors with a select crew of 70, including Japanese animation pioneer Kenzo Masaoka (1898-1988) as director of shadowgraph. The almost 50,000 animation cels that compose the film was achieved through a big budget at that time (¥270,000, equivalent to about ¥600M or $5.5M dollars today), making it a remarkable achievement for the period. Because most of the nation was swept up in the wartime effort, few saw the movie in theaters when it was released. Though the film was believed to be lost after the war, a negative copy was later discovered in 1983 and the movie was re‐released in 1984. In order to successfully create the restored print, Shochiku scanned a 35mm master print and internegative in 4K and restored it in 2K.

After the film was re-released in 1984, Mitsuyo Seo wrote a message regarding his creation:

I began making this film in September of 1943 when I joined a navy boot camp for paratroopers in order to carry out research for the script. I spent about a week with the unit, and was accompanied by the late great artist Saburo Miyamoto, who had been commissioned to make war‐themed paintings. My observations of activities at the base, the interiors of planes, battle maneuvers and more formed the backbone of the film.

I hit a snag when it came time to begin drawing the cels because most of the staff of “Spider and Tulip” (Kumo to Churippu), who were scheduled to work on my film, had been conscripted by the military. For that reason, I called in art department staff from Shochiku’s Ofuna studio as well as members of Shochiku’s publicity department who had art skills and gave them a crash course in the craft of animation, and these makeshift animators enabled the production to continue. We started out with a crew of around 70. They all burned with the ambition to make Japan’s first feature‐length animated film, and devoted themselves wholeheartedly to the endeavor.

The entire sound for the film was prerecorded and a triple‐level multiplane camera stand was used to shoot it’s about 50,000 cels, which were new technical approaches to animation in Japan. However, due to staff members being called up by the military during the making of the film, the production team got smaller and smaller, and only 20 remained by the time the film was completed. One animator died in combat at the South Pacific front, while one background artist was killed in an explosion at a munitions factory, and even after the war ended, the staff members who returned to Japan after being demobilized or discharged eventually passed away one after another without getting a chance to see the film, and [at the time of the film’s re‐release in 1984] only nine are still alive that I am aware of.

However, now this legendary animated film is no longer merely a legend. I’m overjoyed that this culmination of the strenuous efforts of its crew over 14 months has re‐emerged into the light to be resurrected on the silver screen.

Numerous animation legends such as Osamu Tezuka and Isao Takahata have credited Mitsuyo Seo and Kenzo Masaoka as having influenced their work. While the film is a piece of propaganda created to maintain nationalistic values during World War II, it represents a major step in Japanese animation history. Whether you agree with what the film says or not, it is one that should be seen by all fans of animation: Momotaro, Sacred Sailors is part of the time capsule that encompasses the animation revolution of the early to mid 1900s, and its influence is paramount in how Japan became just as much of a powerhouse in animation as America did with Walt Disney.

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page