Ah, burnout. There comes a point when we all experience it. While many of us may feel burned out by work, I’m sure there are just as many who have been burned out by their studies. Lately, I’ve been feeling burned out when it comes to studying Japanese; every time I try to focus, my mind wanders. The prospect of studying Japanese, what once filled me with curiosity and a sense of improvement, now feels like I’m constantly throwing myself against a wall as if that’ll get me to start climbing (protip: that won’t help you climb a wall). What are we supposed to do? Continue smashing our bodies against that wall until we can just walk through it? There’s only so much one can stand. So, how should we deal with burnout?

What exactly is burnout?

Original Meaning

Before attempting to tackle our own burnout, I thought it might be useful to look at the history of the term in the field of psychology. Herbert Freudenberger was the first researcher to address the phenomenon under the name “burnout,” using observations from his time as a volunteer. Researchers Christina Maslach and Susan E. Jackson later developed a questionnaire to assess burnout. It analyzes a person’s level of burnout along three dimensions:

- Emotional exhaustion “feelings of being emotionally overextended or exhausted by one’s work.”

- Depersonalization describes an “unfeeling and impersonal response towards recipients of one’s care or service.”

- Personal accomplishment describes “feelings of competence and and successful achievement in one’s work.”

Although the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) was created with health and service workers (police officers, nurses, etc.) in mind, I couldn’t help but relate to a number of the questionnaire responses. For example, respondents experiencing burnout tended to be dissatisfied with their job growth the more emotionally exhausted they were. Those with a sense of low personal accomplishment also tended to feel like their work lacked meaningfulness. Those with high depersonalization scores were also more likely to take more frequent breaks and have more absences, along with having the desire to spend less time with people. Dissatisfaction, lack of meaningfulness, and frequent breaks? Check, check, and check.

Only Occupational?

Dissatisfaction, lack of meaningfulness, and the desire to be alone? I’ve been there too many times to count. It’s also worth mentioning that some researchers support the notion that burnout is a form of depression since some studies have found no diagnostically significant difference between the two. However, occupational burnout is not currently recognized as a distinct disorder in the DSM-5. There’s also increasing support to expand the scope of occupational burnout beyond being work-related. Thinking about it, you could become burned out on a lot of things: hobbies or interests that you want to improve on but have difficulty with; school work that leaves you drained and ceases to seem worthwhile; and taking care of loved ones who are dealing with serious mental or physical issues. You can feel burned out on practically anything, including, of course, your Japanese studies.

What is making you feel burned out?

Now, clearly, I am no expert with regards to most things. I can only speak from experience, and even then only with regards to studying Japanese. These are the things I’ve thought about for myself, and I encourage you to consider your own disposition regarding them.

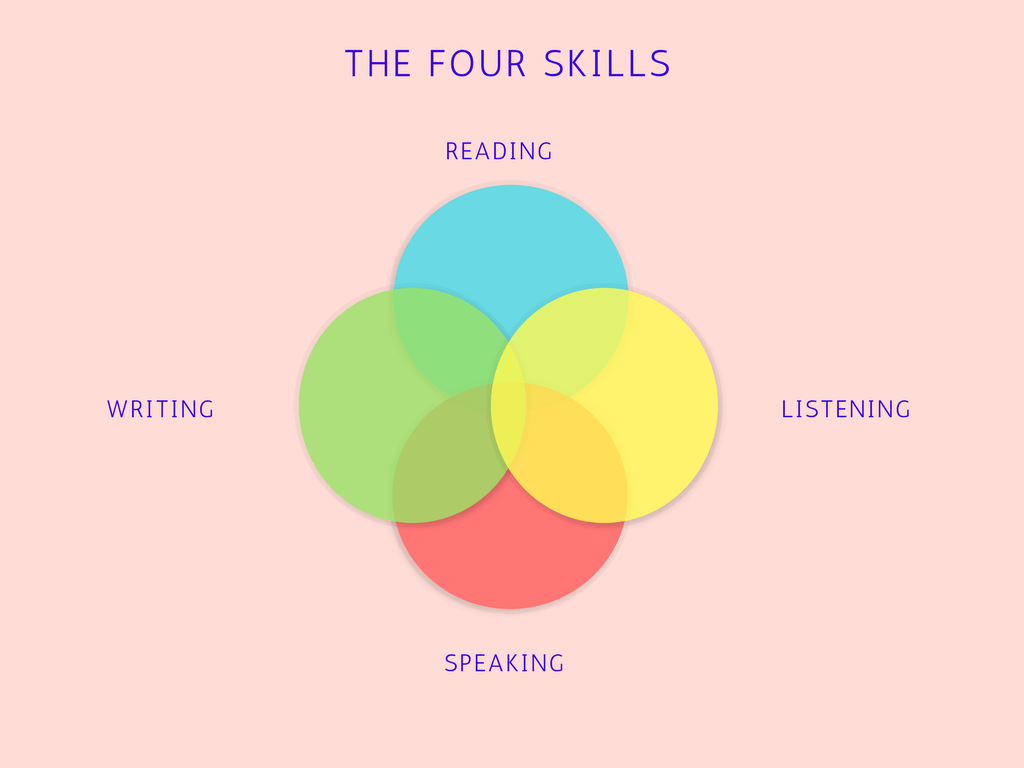

The Four Skills

When it comes to communicating in a language, there are four general skills: reading, writing, speaking, and listening. I know what some of you are already thinking: “Cindy, I suck at all of them.” While I can neither confirm nor deny that, I do understand your perspective. This is because I also think these things about my own skills. For now, though, which one is both your weakest and the one that means the most to you when it comes to progressing? This goes back to the question “Why are you learning Japanese?” Watching anime? Then listening. Reading books or manga, or playing video games? Then reading. From there, you need to get specific with your frustration: “I mix up certain kanji all the time,” “I can never remember more advanced grammar,” “Japanese people talk way too fast for me to understand,” etc. The reason for doing this is to see if we can pinpoint your frustrations to one or two very specific things. This way, coming up with solutions will seem less daunting.

“Cindy, listen. I’m so far gone that just the thought of engaging with the language is draining and unappealing.” I get it. I’ve been there, too. When you don’t even want to attempt the endeavor of studying, it can seem as if your days learning Japanese are over. But, there may still be a way to move past this blasé feeling.

Solutions (well, hopefully)

General Burnout

Let’s begin with those completely avoiding their studies. I want you to think about why you started learning Japanese. I don’t mean that you should give a laundry list of reasons. What I’m talking about is this: what was the moment for you when you thought, “Yes, I’m going to try to learn this language”? I want you to revisit the thing that sparked that thought and set you off on your language journey. My suggestion is to re-experience the thing that filled you with enough passion to start learning a foreign language.

Let me use myself as an illustration. I’ve had burnout on and off ever since taking the JLPT back in July. (I think it’s because I studied so intensely leading up to the exam.) At first, I thought I failed it again, but when the results came in, I found out I had passed. While I was happy, I still knew that I didn’t have a firm grasp on the material I reviewed before the test. It started to feel like a hollow victory after a while. Thus, I didn’t know where to go from there. (Cue all the goofing off that ensued.) One evening, though, I started listening to a bunch of Japanese songs that I had discovered when I was younger. Listening to them brought back those old feelings of when I first came across Japanese music. I still loved those songs, and I still wanted to understand the lyrics to them. I was ready to stop studying out of habit, and start studying out of passion. This was extremely vital; there’s no point in learning a language if you don’t actually feel the want to learn it.

Moving Towards Specifics

With more specific troubles comes even more reflection. Earlier, I mentioned the four general language skills: speaking, listening, reading, and writing. I asked you to pick one of those to work with when thinking of your weakest skill. The following are things I’ve considered for my own language-learning process, and they’re ones I think you should also go through:

- Look at your past study methods.

- Separate the methods you like to use and the ones you don’t like to use.

- Ones you like: did these actually help you learn and develop your skills?

- How?

- Did you stop using any of these? Why?

- Ones you don’t like: why did you add them to your routine?

- Do they benefit you in any way?

- If you’re still using these methods, why? What can you do to make them more enjoyable?

The point of all this is to see what works and what you like. Your aim is to come up with effective study methods that you enjoy doing. It’s also to get you to think about how to make the things you enjoy more effective at helping you learn. Maybe you love playing video games, but when you play them in Japanese, nothing really sticks. How are you using games as a tool? What can you change to get more out of playing games in Japanese? That’s the sort of thing you want to figure out.

This doesn’t mean you’ll never be bored when you study.

I know not every aspect of studying is going to be fun all the time. However, if you have a number of fun activities in your arsenal that help you improve, you can always whip them out whenever you start to get fatigued by the more trying times. Sick of doing flashcards? Listen to a Japanese song and work out what some of the words mean as you sing along. Tired of looking at seemingly endless pages of kanji? Hit play on a podcast about whatever subject you’re into and see how much you can understand. (Don’t be afraid to adjust the speed!) Frustrated that you still can’t understand what people are saying in a J-drama? Try reading some manga out loud so you can hear what’s being said. If you have enough variety in your studying arsenal, you can switch out activities you’re burned out on, rather than becoming burned out yourself.

What if I start to feel burned out again?

The key for avoiding burnout after doing all this boils down to continual reflection. Can you feel yourself getting bored, but you have a lot of flashcards to go through? Do them in small chunks and maybe listen to a favorite song in-between. Power-studying tends to tire people out more quickly. You’re not in this for a final test in the morning; it’s a long-haul sort of deal. You can also keep a journal with your goals for each day, along with a list of your accomplishments. Maybe reflect each week on small things you’ve improved on. Every month, reflect on larger, more general improvements. Ultimately, you want to recognize right away when your time studying is veering off course and correct it. If you keep these things in mind, it’ll be much easier to keep potential burnout in check.

How do you avoid burning out when you study? What do you do to bounce back from being burned out? Let us know in the comment section below! Happy studying~! φ( ̄ー ̄ )ノ

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page