Content warning: The screenshots featured in this piece contain blood and scenes of violence.

Spoiler warning: This piece features some spoilers for the events of The Hundred Line: Last Defense Academy. That said, while I touch on conceptual ideas and certain gameplay features, I left the explicit details of the story as vague as I could.

Takumi is an ordinary teenage boy living an ordinary life. That is, until he and his friend Karua are attacked by aliens one day. They are saved by a mysterious mascot named Sirei, who offers Takumi a red knife-like weapon called an infuser. Takumi stabs himself with the infuser and unlocks his special hemoanima powers.

Before he can ensure Karua is safe, Takumi is whisked away to Last Defense Academy. There, he must fight together with over a dozen other weird teenagers to save humanity from destruction. At least, that’s what Sirei says. But is that really the truth? What secrets are hidden behind the walls of Last Defense Academy?

Two giants

The Hundred Line: Last Defense Academy is a collaborative project by two giants of the visual novel space. One is Kazutaka Kodaka, who created the mystery thriller series Danganronpa alongside character designer Rui Komatsuzaki and composer Masafumi Takada. The other is Kotaro Uchikoshi, who contributed to the cult classic visual novel Ever-17: The Out of Infinity before finding wider success with the Zero Escape series.

Kodaka and Uchikoshi left their previous workplace, Spike Chunsoft, to form the new studio Too Kyo Games. There, they co-developed various projects including video games (World’s End Club) and anime series (Akudama Drive.) Hundred Line is the studio’s most ambitious project yet: a strategy adventure game with a hundred endings, plus a prologue as long as a typical Danganronpa title.

Hundred Line plays like what you’d expect from a Kodaka and Uchikoshi collaboration. Like Danganronpa, the game stars a large cast of absurd caricatures you grow to love. Like Zero Escape, they are trapped in a metaphysical mystery box they must solve in order to escape. In the process, they monologue about concepts like “hope” and “despair” (Danganronpa-coded) as well as pseudoscientific concepts like “cryptoglobin” (Zero Escape-coded.)

Defying expectations

Of course, there are twists. Kodaka and Uchikoshi built their careers on defying player expectations. Uchikoshi, in particular, is infamous for his final act reveals that demand you reassess everything you’ve experienced so far. Are you really playing as the character you thought you chose in the introduction? Could the game’s narrator have its own agenda? When does the game take place, anyway? Uchikoshi often reuses the same tricks, but they’re good tricks.

Kodaka, on the other hand, is more about cultivating an adversarial relationship with the player. From changing the identity of the first killer between the original Danganronpa’s demo and full release, to writing a villainous character in the sequel with the same voice actor and almost the same name as the hero from the original, his games bait your expectations before snatching them away and laughing in your face. I’d even go so far as to say that Kodaka’s games prioritize shock value over being functional mysteries.

After the prologue

Hundred Line’s most notable new addition to Kodaka and Uchikoshi’s respective formulas is its size. After its prologue, which lasts for about twenty to thirty hours, the game opens up into a massive choice-based structure with at least twenty distinct routes. These routes vary in length, theme, and content. Some are comparable to the prologue. Others go on weird tangents or take the characters into entirely different genres. A few are so frustrating that you suspect the developers included them on purpose to mess with you. Even after you’ve played through the core routes of Hundred Line, like Kodaka’s “2nd Scenario,” many surprises lie in wait.

Which raises the question: How do you keep surprising the player over such a long period of time? For one thing, it’s tough to keep somebody in suspense for over a hundred hours. That’s why most effective horror games are short. For another, games are expensive to make. Creating unique art assets to sell twists and turns requires money and time. These are qualities that Too Kyo Games did not have in large supply; in fact, the studio had to go into debt in order to finish their game.

One hundred days

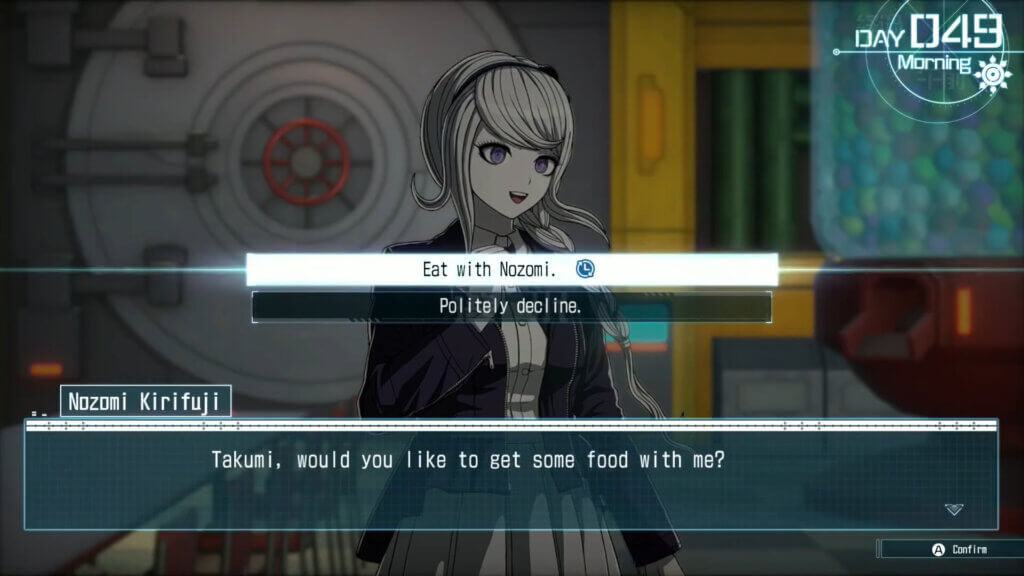

Their solution is effective, but also deceptive in its implementation: Hundred Line is built around repetition. Every “day” in its structure begins with a message from Sirei on televisions installed in each student’s room. Then, the cast meets for breakfast in the Last Defense Academy’s cafeteria. After the events of the day, Sirei gives a final message, and Takumi monologues to himself before going to sleep. Scattered among these days are story sequences, tactical battles with aliens, and “free time” segments where Takumi speaks with friends, raises his stats, or gathers resources to invest in items and special abilities.

While this structure shares similarities with the Danganronpa series, it is also clearly influenced by the Persona games directed by Katsura Hashino. Hashino’s team at Atlus grafted dating sim mechanics onto Atlus’s role-playing design. In doing so, they set a status quo that other game studios (like Falcom and Intelligent Systems) would pursue for the next decade.

Yet, Hundred Line is not just a Persona-like. Fixating on the game’s time management system misses the forest for the trees. That is because Hundred Line builds on an aesthetic inspiration that goes back not just to the first Danganronpa game, but to another medium entirely.

Stock footage

Since the production of Astro Boy in 1963, the Japanese anime industry has been defined by compromises. How do you make something as complicated and expensive as animation in time to air on a weekly schedule? Some studios limit their workload, train their employees, and give themselves plenty of time. Others ride the edge of total breakdown for the length of their production. Then, there are those who develop techniques that allow for creative expression while reducing the workload.

One of the most famous of these techniques is stock footage (or, as it’s called in Japan, “bank footage.”) In its simplest form, the idea is: Why animate a magical girl changing forms, or a giant robot using its special attack, multiple times when you can just animate it once and then reuse that sequence over and over? The resulting sequence tends to stand out from the rest of the material, and the viewer may very well notice the artifice. But the ritual nature of stock footage can be satisfying in its own way.

Dirty tricks

The other great thing about repetition is that once the audience is used to it, it becomes that much easier to shatter their expectations. For instance, a giant robot could use its special attack against the enemy; but this time, after forty-nine episodes of surefire success, it falls short. Another example: the magical girl transforms into her alter-ego, but this time you don’t want her to transform, because she might die if she does. These dirty tricks only work if you condition the audience weeks in advance.

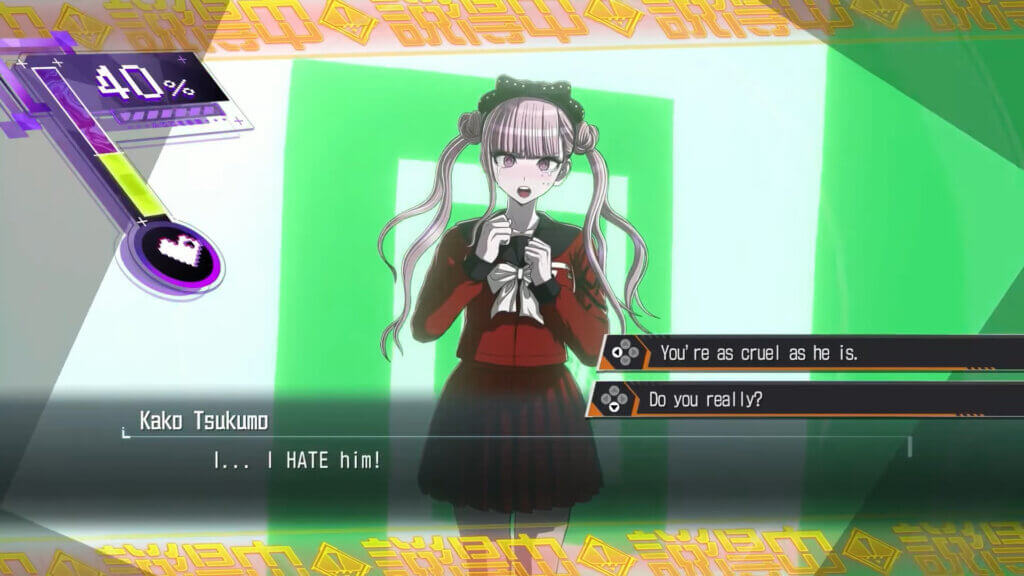

Hundred Line is loaded with the video game equivalent of “stock footage.” There’s the aforementioned time mechanic, where the structure of each day repeats itself with small variations. There’s the use of repeated cutscenes when the protagonists activate their hemoanima, or when alien invaders besiege the school. These rituals are baked into the game’s systems.

Execution

The most memorable of these are the execution scenes. Most battles in the game end with a fight against an enemy commander. Defeat them in combat, and the player is given a choice as to which student will absorb their hemoanima. That student stabs them with their infuser and triggers a rain of blood, followed by the words “EXECUTION COMPLETE.” Each character has their own visual and audio gag: some are serious, others sadistic, and one even barfs after doing the deed.

The execution ritual does so much to set the tone of the game. First, because it’s extremely stylish; the sequence is stained red, and each character is rendered in black and grey. Second, because it offers a nugget of extra characterization for every member of your army, showing how they cope with violence. Third, because it complicates the simple “humans versus invaders” narrative of the game. The execution scenes are shot not from the perspective of your heroes, but from the perspective of the victims. That’s enough to make just anybody ask, “Is this really such a good idea?”

That spiral staircase

Hundred Line is certainly influenced by the NieR series of games, which also build their stories around cycles of violence encoded in recycled mechanics and art assets. But I would sooner point to another influence that I know is one of Kodaka’s favorites: the anime director Kunihiko Ikuhara. Ikuhara made his mark on the industry by contributing to the anime series Sailor Moon. Every work he has directed since has kept Sailor Moon’s use of stock footage and repetition, but interpreted by way of David Lynch’s gut-wrenching audio and visual design.

Kodaka has made no secret of his Ikuhara fandom. (He admitted as much in an Archipel interview.) The second Danganronpa game features Penguindrum voice actress Miho Arakawa as the “Ultimate Princess” Sonia Nevermind. The video game Master Detective Archives: Rain Code has the protagonist pull a “sword of truth” from the mouth of a shinigami to help solve mysteries, just like Utena pulls the Sword of Dios from Anthy’s chest in Revolutionary Girl Utena. The finale of the anime series Akudama Drive is just a more literal take on the climax of the Utena movie, where two characters escape drones on a motorcycle and leave for another, ambiguous world.

Transformation

That influence can be seen in Hundred Line, as well. Takumi’s dreams of his childhood friend Karua, for instance, borrow their blocking directly from Penguindrum. But rather than explicit plot elements or visual motifs, I think the game’s clearest link with Ikuhara’s work is its use of stock footage. Just like Utena features charismatic repeated sequences like the heroine climbing a spiral staircase, Hundred Line has its executions, hemoanima transformations, and other sequences that make up the game’s grammar.

Why repeat scenes in this manner? Well, well-made stock footage is satisfying to watch. The audience anticipates it as part of the storytelling rhythm. It’s also a great way of setting and then breaking expectations. It comes as a shock, for instance, when the party healer Nozomi is revealed to transform through an entirely different method than the other characters. Or when one of Takumi’s friends steals an execution without offering the player a choice. My favorite gag is when the Last Defense Academy theme music is changed up for a rock remix exclusively on the 69th day. Nice!

The risks of repetition

Hundred Line is also very good at finding creative ways to spin past assets. You thought fighting one commander at a time was bad enough? What if you had to fight two of them, and then they fused together? Then, there’s the game’s greatest debt to the NieR series: the commander introductions, which are initially voiced in an alien language the first time around, are translated into English after the prologue. Thus, every battle’s cutscenes are recontextualized without having to create new ones.

Repetition has its risks, of course. Its use inevitably generates friction. Sometimes this appears to be by design, like in routes that subject the player to several grueling battles in sequence. At other times, it comes off as a cheat; a means of making the game longer. The “free time” sequences especially kill the story’s momentum. While these are necessary to give the player a chance to decompress and level up their abilities, they also contribute to the feeling that Hundred Line prioritizes scope over consistency.

Secret weapon

What keeps the game from spinning out of control is Kodaka and Uchikoshi’s instinct for eliciting reactions from the player. Just when your interest starts to flag, any one battle, cutscene, or music track is tweaked just enough to leave you guessing what else the game might have up its sleeve. It’s a process of call and response that’s just as applicable to Kodaka’s sadomasochistic tendencies as it is to Uchikoshi’s fondness for locked room mysteries.

Hundred Line features hundreds of unique illustrations and several dozen music tracks. It is the closest you’ll find these days to a prestige visual novel in a medium where games are routinely starved for resources. Yet, I’d say that its greatest strength is not its scope, style, or range of assets. Hundred Line’s secret weapon is just how much it can squeeze out of very little. Whether or not Kodaka thinks he can (per his Archipel interview) “replicate scripts from Penguindrum or Revolutionary Girl Utena,” the game’s structure speaks for itself.

To find more information about The Hundred Line: Last Defense Academy, visit their website (warning some flashing). You can purchase the game on Switch and PC (Steam).

Article editor: Anne Lee

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page