For this series, I’ll be placing a spotlight on some of my favorite creators in the manga industry (mangaka). We’ll take a look at their manga series (legally available in English), and some neat tidbits about the creation behind those manga, occasionally including details from the mangaka’s personal life. Let the emotional rollercoaster begin as we discuss the works of Inio Asano!

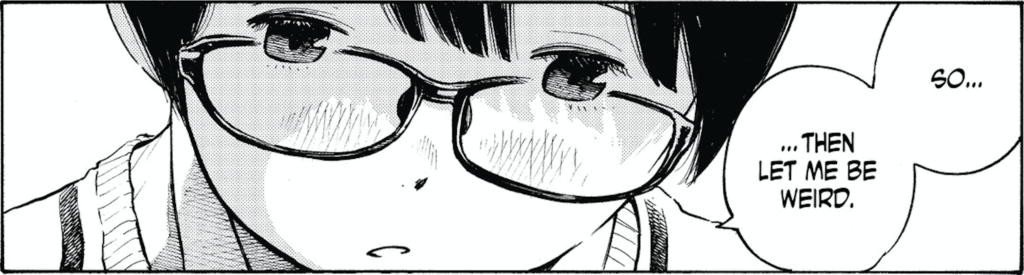

“What a Wonderful World!” (2002 – 2004)

While this isn’t the first manga Asano worked on, What a Wonderful World! is the earliest of his works to be licensed in English, so this is the one we’ll be starting off with.

Now, I know I promised depression, but this is actually one of Asano’s more inspirational and uplifting works. However, I wouldn’t expect all sunshine and rainbows. Nope, if you are currently a person that exists, you probably know that life can be really mean and unfair. But you might also know that joy can be found, and sometimes in the unlikeliest of places. Asano seems to think so, as he tackles these subjects in this manga by giving his readers a peek at the intersecting lives of several characters living in modern-day Japan.

Life can be painfully mundane, and you may feel like you’re just going through the motions. You might have relationships that have broken off or are teetering on the edge. This could be due to neglect or simply the busyness and unexpected occurrences that life throws your way. Getting to a place of joy can take effort, and maybe even a change of perspective, but if you wait long enough, some good is bound to come your way eventually, right? Asano attempts to answer this question in What a Wonderful World!.

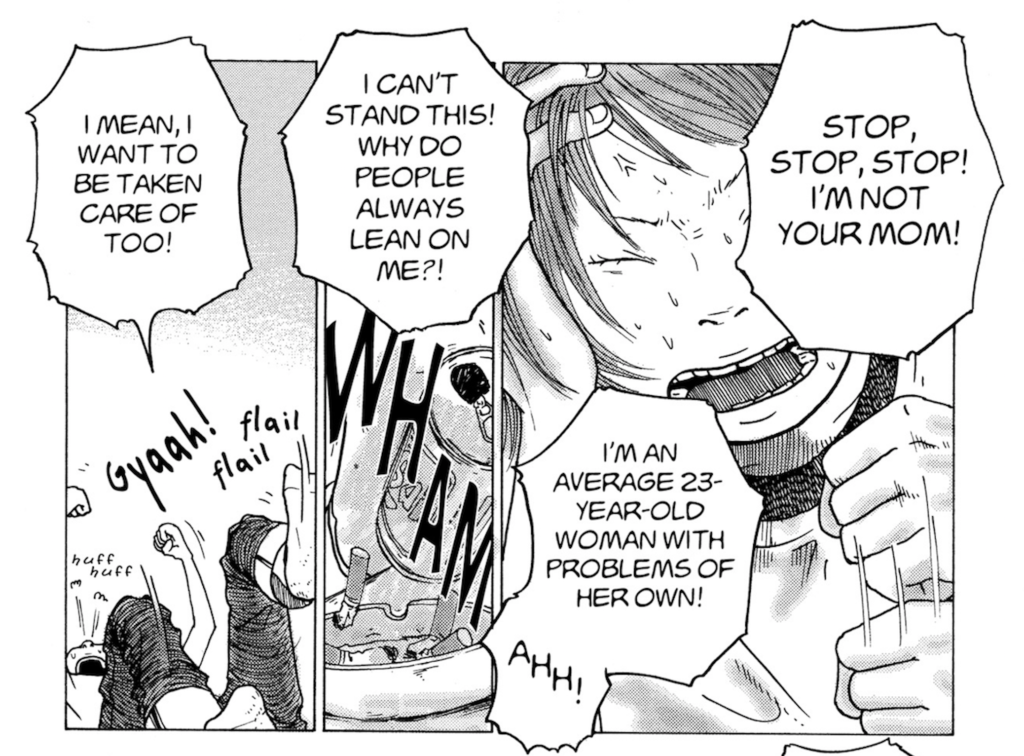

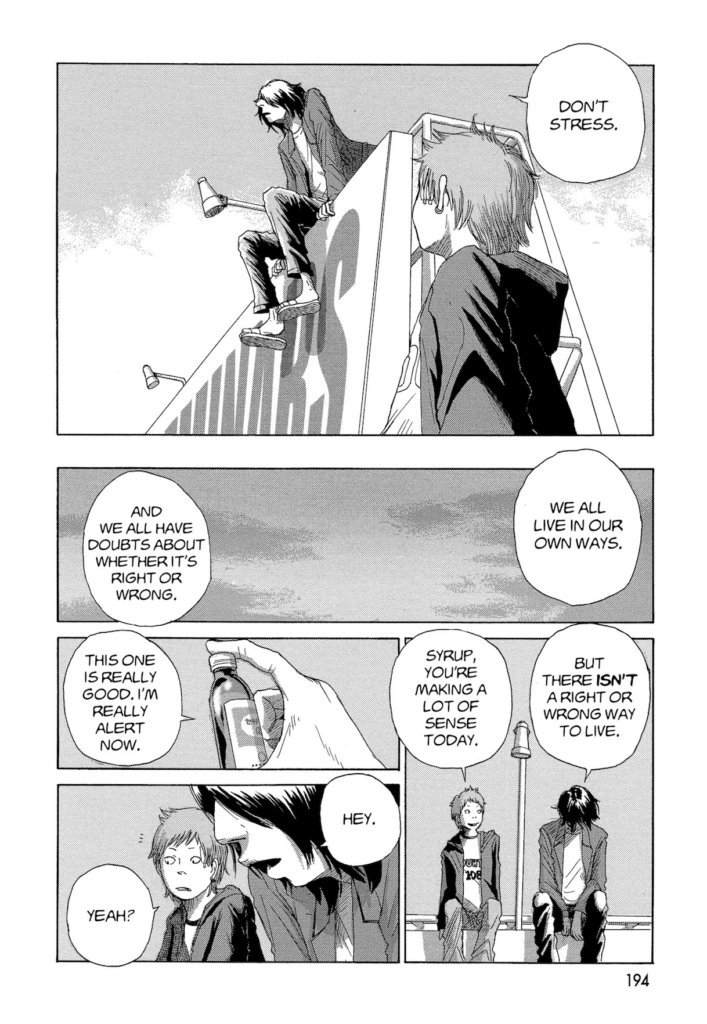

As in most of Asano’s works, there is a nice mix of characters here, old and young, male and female. Each person is in some sort of transitional period of their life, struggling with very real problems. A lot of those issues overlap, but each circumstance is different. No matter what is going on, Asano is able to effectively communicate these situations, because of his attention to detail and focus on realism. This largely has to do with how natural his characters’ dialogue is, which is no coincidence. Asano has stated that he doesn’t agonize much over the stories in his manga, but instead focuses on the dialogue of the characters and the nuance behind it.

So, when he writes a scene where a girl is venting to her older sister (because she’s living with her boyfriend in a situation that isn’t financially stable), I can believe it, despite having never been in that situation myself. Or when he decides to go a little more outlandish and presents another story about pursuing your dreams and moving forward in life… using two cram school students and a homeless man addicted to cough syrup who wishes to fly. And when you start thinking “that was weird,” he’ll throw in some supernatural elements to show you he can go weirder and still get you to empathize in the midst of some wacky stuff.

That said, while most of the stories in this manga have accessible themes that anyone can relate to, not every story resonated with me. A majority of the scenarios have clear stopping points (that are sometimes continued in later chapters), but Asano doesn’t always wrap things up in a neat little bow. Sometimes, he introduces things and ends them abruptly, or leaves them up to interpretation. That isn’t inherently bad, but with the offending chapters in this manga, it literally feels like he had some ideas that didn’t pan out, but decided to include them anyway. Thankfully, there are only a couple of very short chapters that have this issue in What a Wonderful World!. This is less of a glaring issue in Asano’s later series, because while there are times he keeps things ambiguous, or ends them in a “life goes on” sort of way, it’s never to the extent where you feel like something was left incomplete.

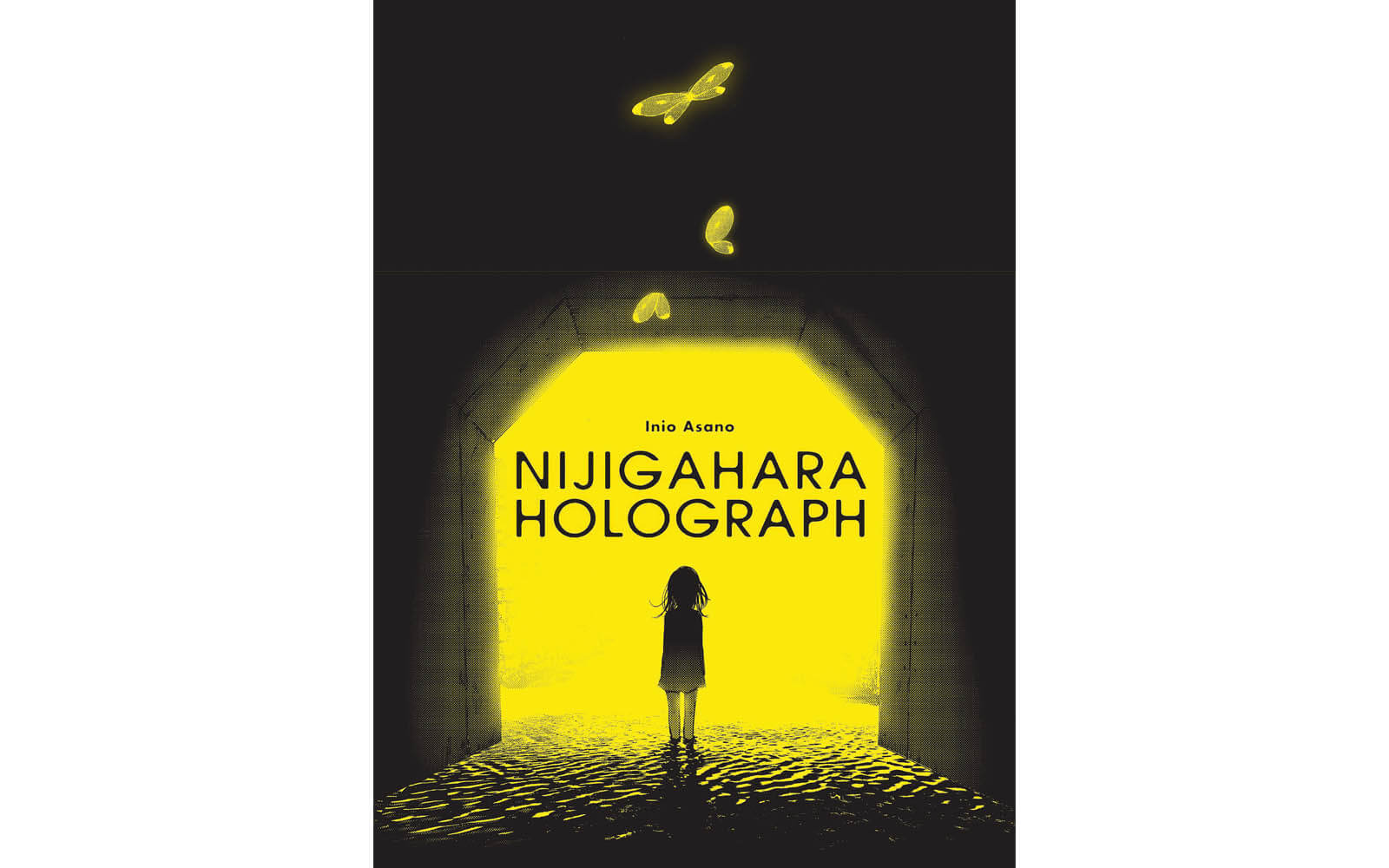

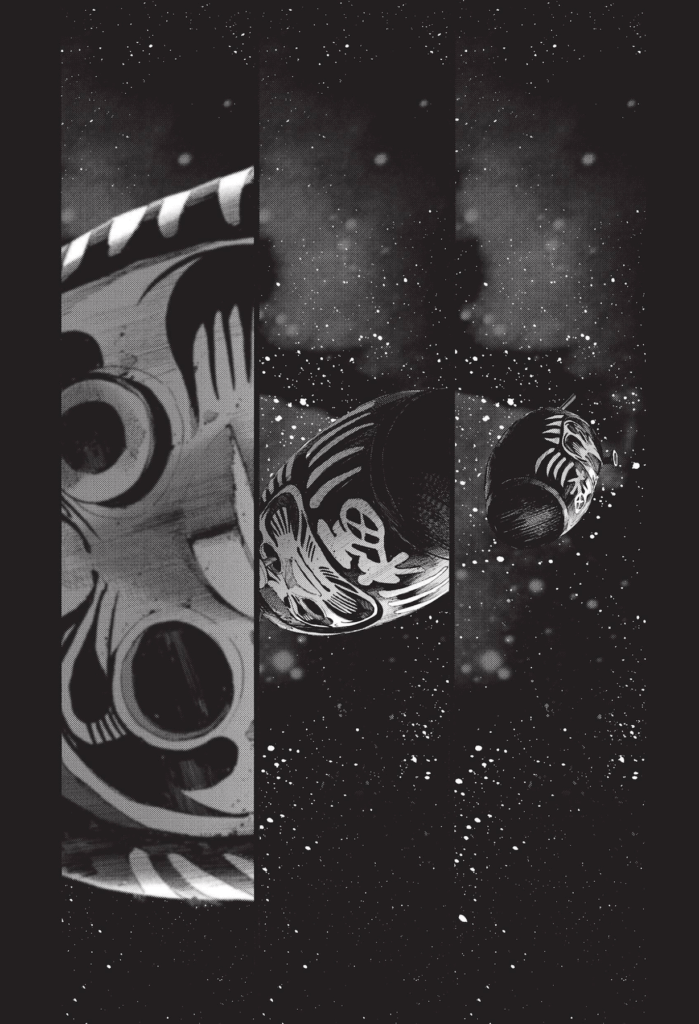

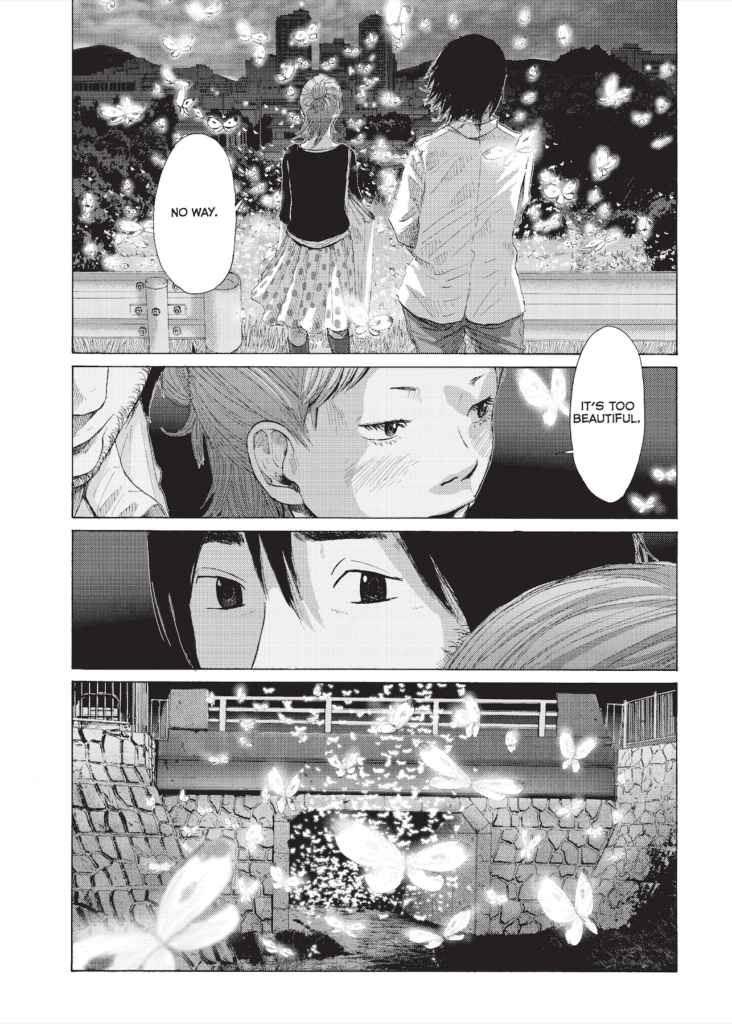

“Nijigahara Holograph” (2003 – 2005)

Speaking of ambiguity, that brings us to Nijigahara Holograph, or Rainbow Field Holograph, which is kind of ironic, because the title implies rainbows, but one look at the cover will tell you this is anything but.

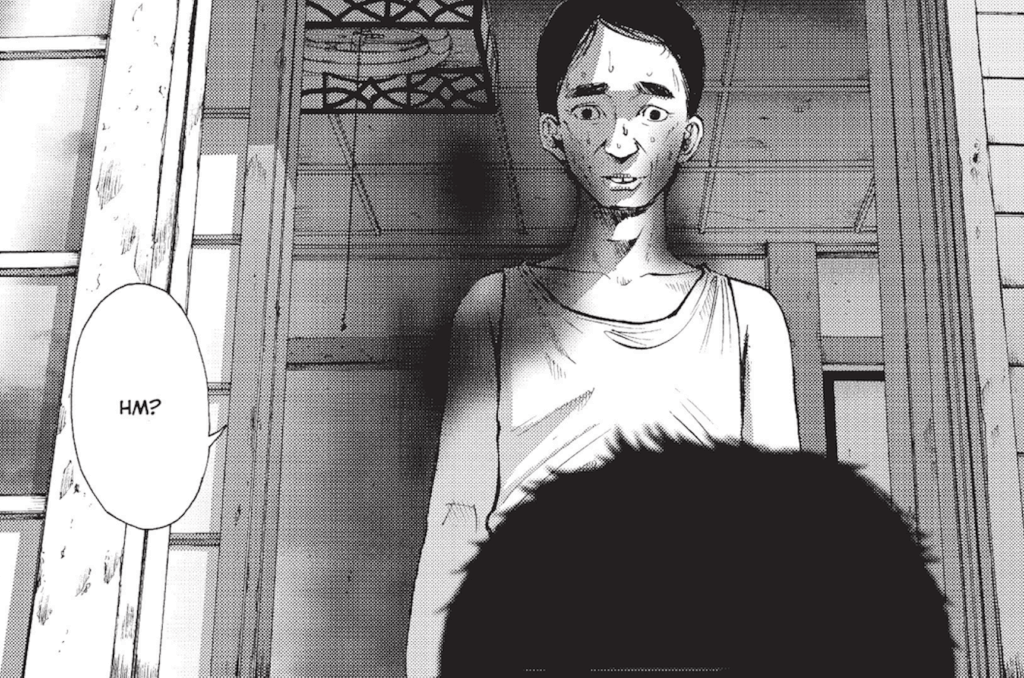

Holograph is probably Asano’s most ambiguous and experimental work to date. Instead of his usual slice-of-life drama, it has more psychological horror elements to it, something his other stories don’t really focus on. It also has a lot more supernatural stuff going on, and can get pretty violent, so if you’re looking for something almost completely different from his other manga, Holograph is a good choice.

However, this manga is one that is harder to take at face value, because the narrative isn’t as straightforward as it is first presented. There are lots of things going on under the surface, and plenty of unanswered mysteries by the end of it. For that reason, Holograph is polarizing. Some critics consider it a masterpiece, but the average reader may feel it’s too surreal and incomprehensible, especially toward the end. Whichever side they’re on, most agree that this isn’t a light and fluffy read. It requires some concentration from the reader and is better served on multiple reads, so this isn’t something you want to lie back on the couch and relax with.

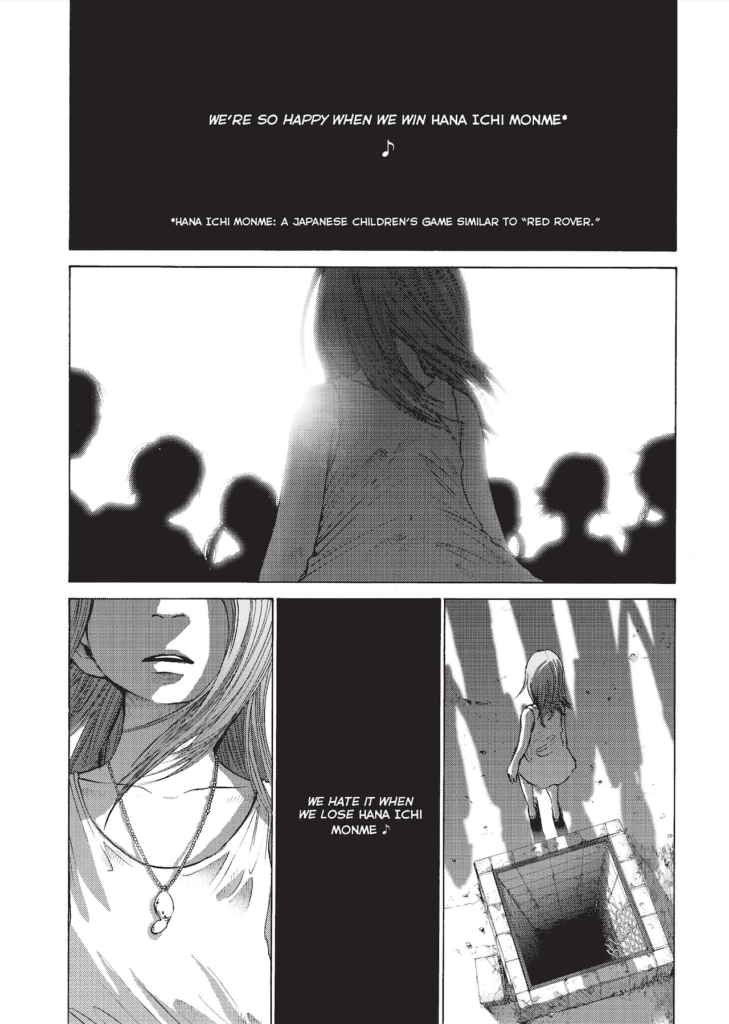

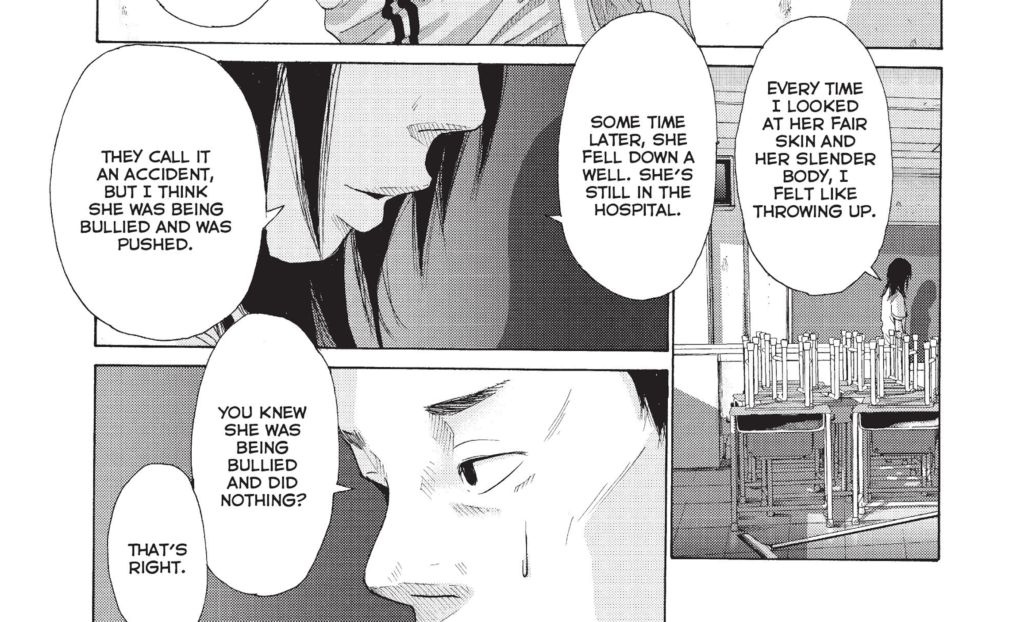

So what is this story about? Good question. Even after reading this a second time for this article and taking a copious amount of notes, I still struggle to piece this together. But at the most basic level, it follows the lives of several individuals after a young girl is pushed into a well and ends up in a coma. Some are trying to forget the past and move on, while others are still haunted by the event (both literally and figuratively). Unlike What a Wonderful World!, all of these characters are more explicitly tied together through the events that take place, and it isn’t nearly as hopeful or lighthearted. In fact, it’s kind of the opposite and shows the much uglier and selfish side of humanity.

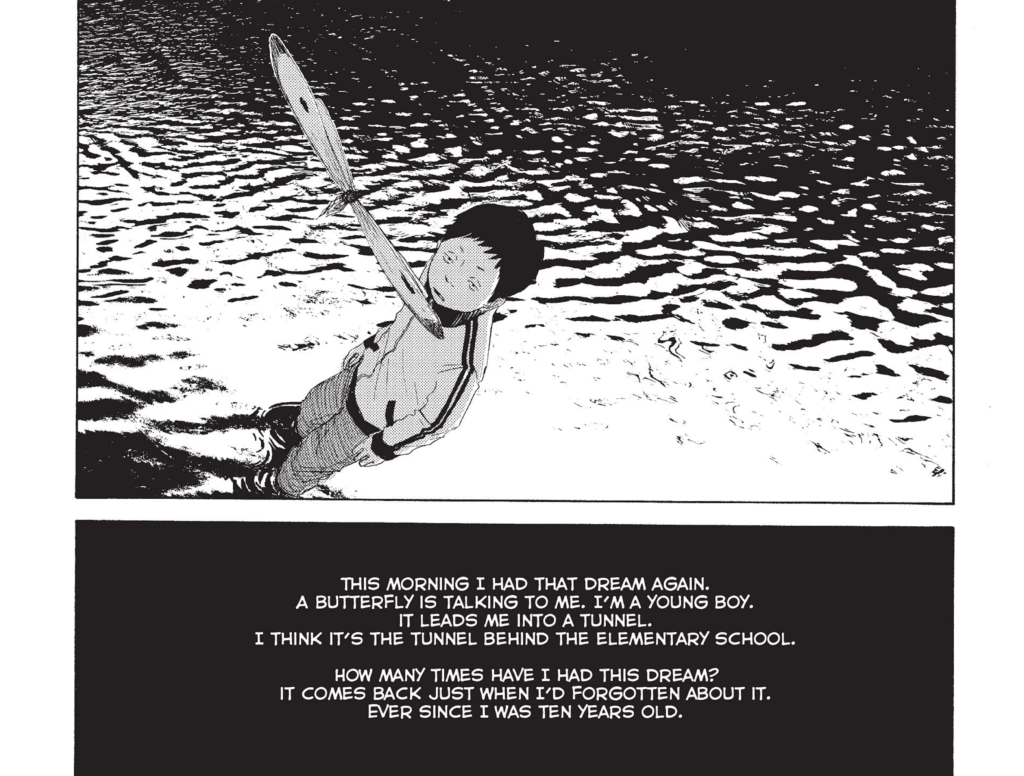

Part of what makes this a somewhat difficult read is that throughout, the manga jumps around in time frequently, so you’ll have a hard time knowing the significance of scenes or relationships if you don’t write down people’s names and keep track of the order of events and other small details. While Asano’s other manga, like Goodnight Punpun, span large blocks of time, it’s usually linear, so those works are much easier to follow. Holograph will jump forward in time to jump back in time to jump to an alternate reality or dream, to jump back to the original reality(?). The story is already confusing by the end, but coupled with these jumps, it can be even more so.

If you noticed in the headline, the original publishing date of this manga was between 2003 – 2005, so Asano started writing this a year after What a Wonderful World! started. When I realized this, I began to wonder how he was able to keep track of such a complicated story while writing an entirely different manga. Turns out, he was totally making things up as he went along. Yup.

While Asano places more emphasis in developing his characters and making their dialogue as natural and nuanced as possible, he does still plan out his stories, but Holograph is one of his exceptions. He admits that the story ended up so filled with riddles that even he forgot what was supposed to foreshadow what. When putting the serialized chapters in book form (tankōbon), he actually added 60 pages and rearranged the structure of the story.

Unfortunately, I don’t know what the original magazine (Quick Japan) serialization of the story looked like, so I don’t know if what he did clarified things or made them murkier. Either way, I was still very confused by the end, but it certainly was a unique experience that may be worth your time if you like stories that force you to dissect them and constantly theorize about the events that took place.

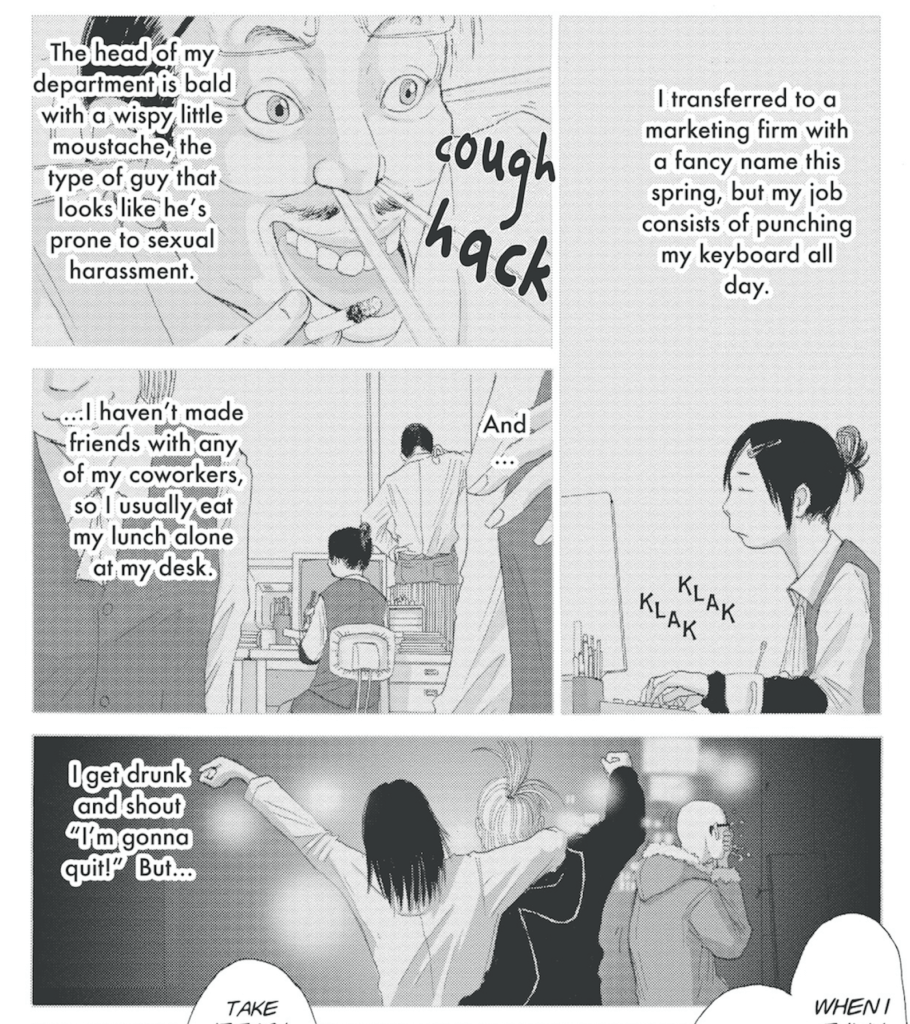

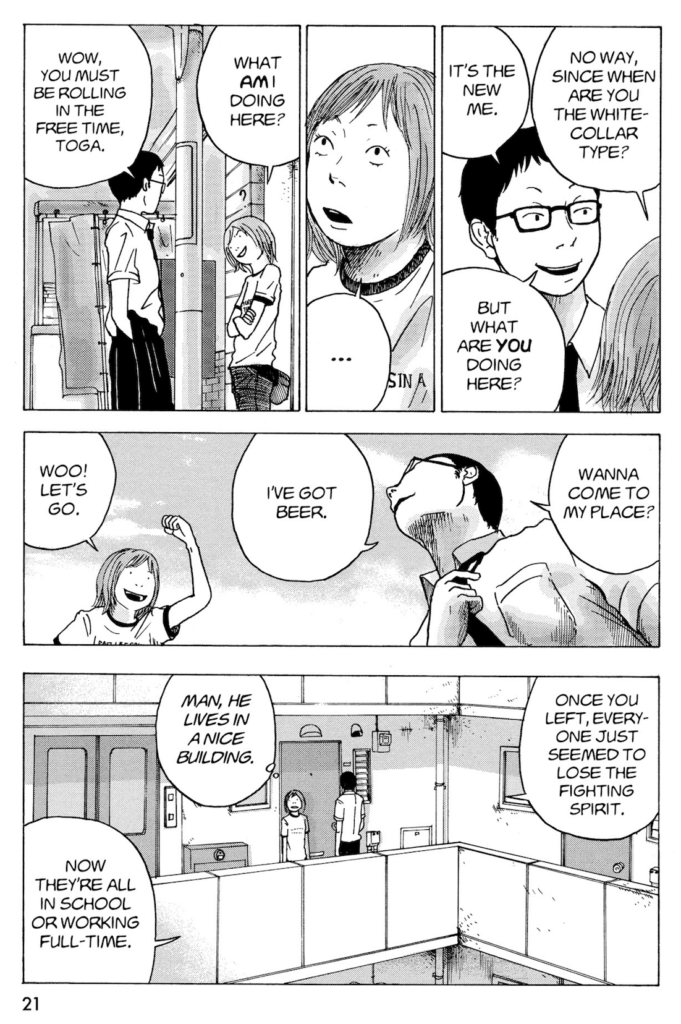

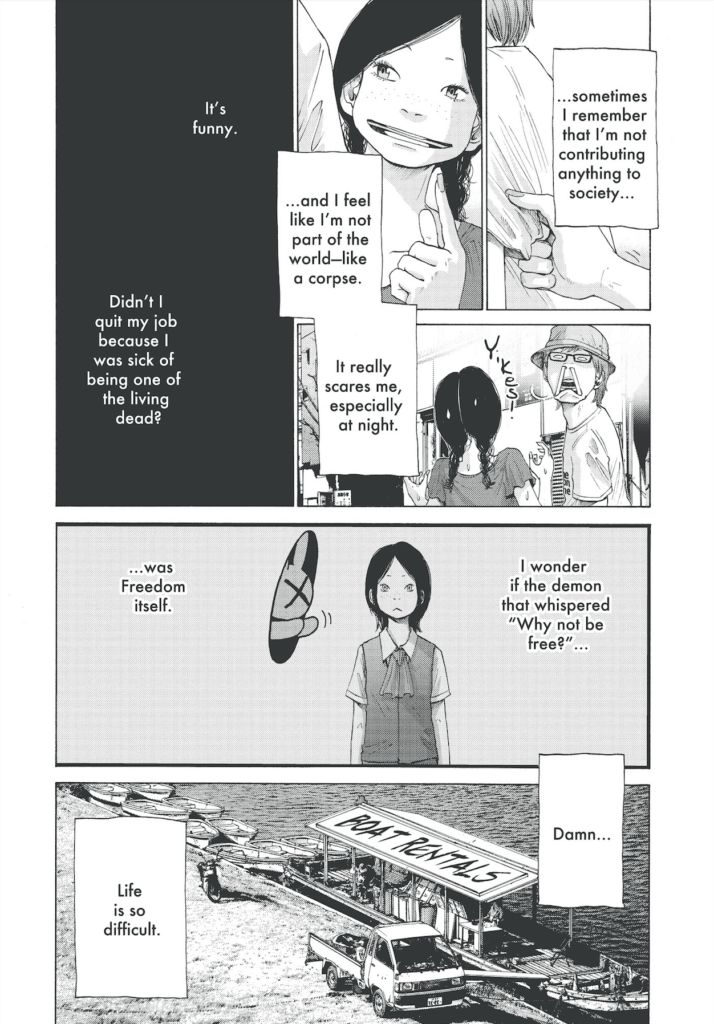

“Solanin” (2005 – 2006)

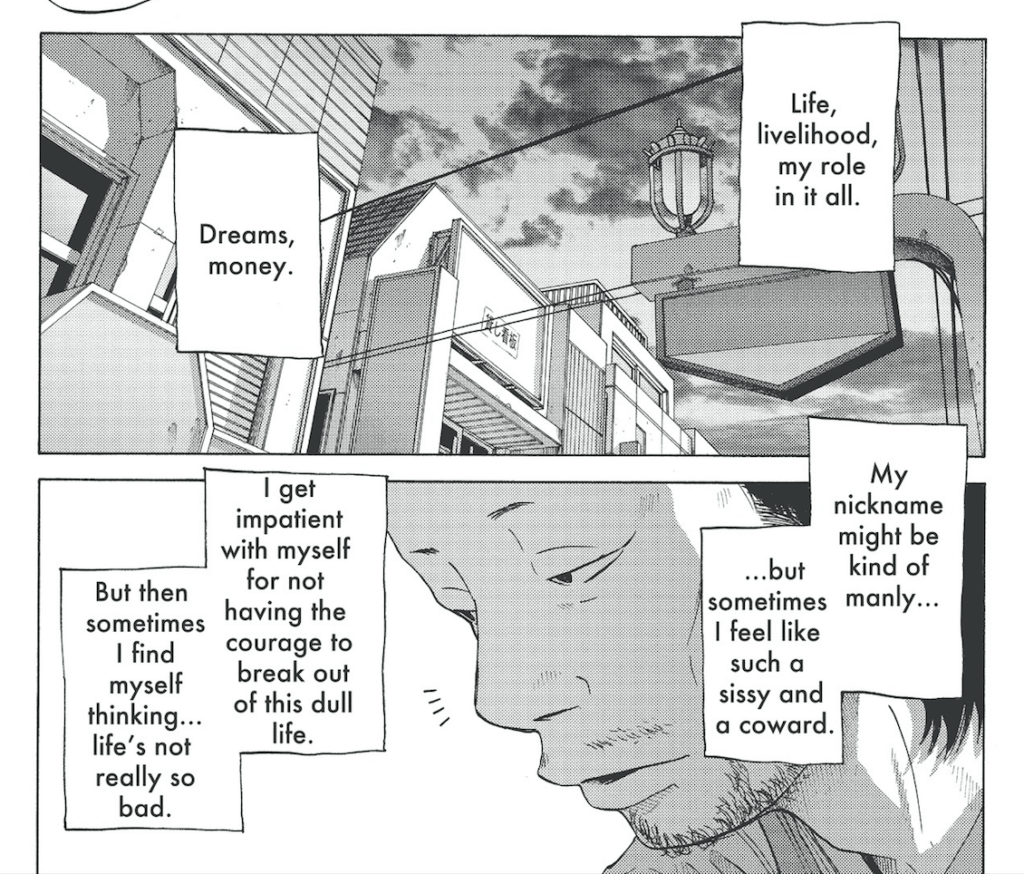

Upward and onward to Solanin! Compared to the past two manga I’ve introduced, Solanin is different in quite a few ways. For one, it ditches the vignette-style approach introduced in What a Wonderful World! and focuses on an even more close-knit cast of characters than Nijigahara Holograph. This is a more personal story about a girl named Meiko and her boyfriend Taneda, as they struggle through adulthood two years out of college. Their story focuses on getting older, escapism, and the meaning of happiness.

Asano does not hold back as he addresses these themes in the story. No, he depicts them so realistically, you’ll almost feel like he was in your head when he wrote this, loosely basing Solanin off of your life experiences or your thoughts. That’s because there are a lot of universal themes present here.

Many can relate to growing old before they know it’s happening. Realizing that in the hustle and bustle, the good times and the tragedies, the world is still moving, and that you can either go with the flow or fight it. In Solanin, some characters try to resist, but because time doesn’t wait, they find they’re just delaying the inevitable. At some point they come face-to-face with reality once more. The characters question their happiness, and they make irrational decisions in desperate attempts to create that happiness for themselves.

Despite these somewhat depressing themes, Solanin has a much more likable and upbeat world and cast of characters. It’s similar to the vibes of some of the characters in What a Wonderful World! except with less crazy circumstances. These characters are still dealing with problems, but it’s kept pared down to everyday issues that most people in their twenties and above can empathize with. That makes this manga one of Asano’s most relatable, which is probably part of why it’s also one of his most popular and well-regarded.

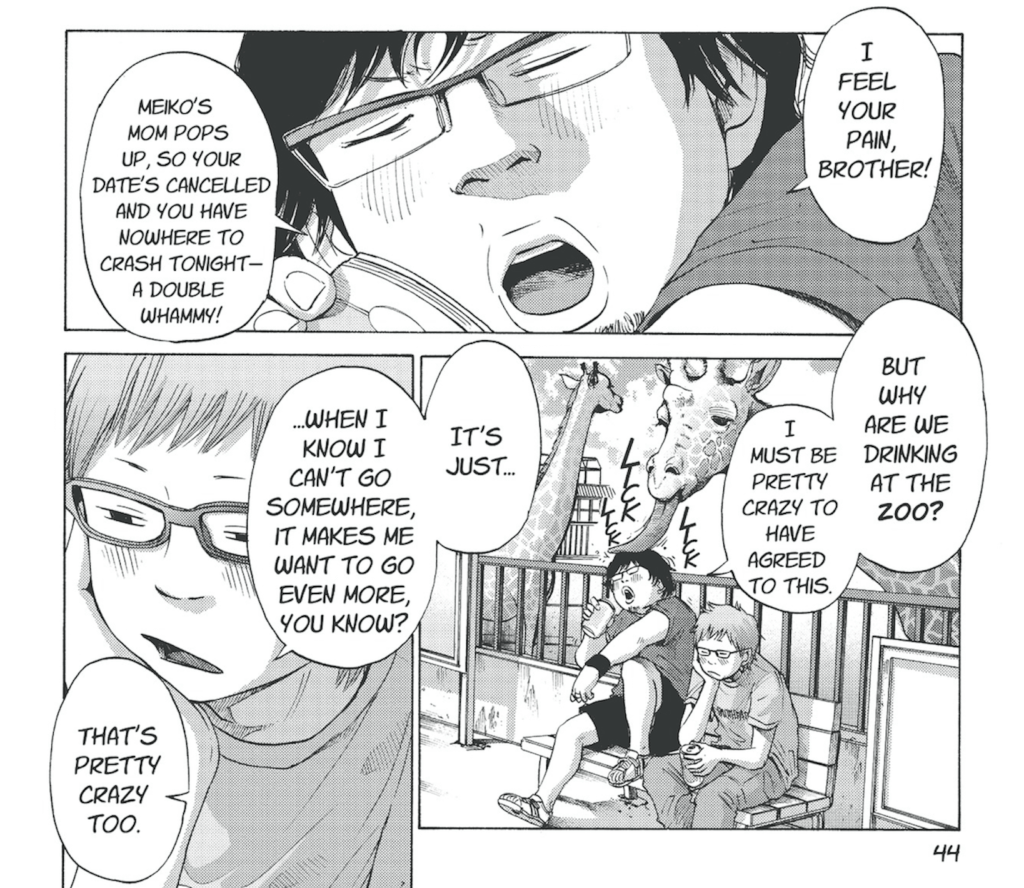

While Solanin is tagged as a slice-of-life, seinen, and drama like his other works, it’s also genuinely funny. Asano doesn’t implant flimsy situations to force humor. It naturally comes out through the way the characters think, when they’re talking about how crappy work is, or when they’re hanging out with their old college buddies and just being goofballs. Even in the midst of hard times, Asano manages to balance everything so beautifully that you never experience the tonal whiplash you might find in other works that try to do the same.

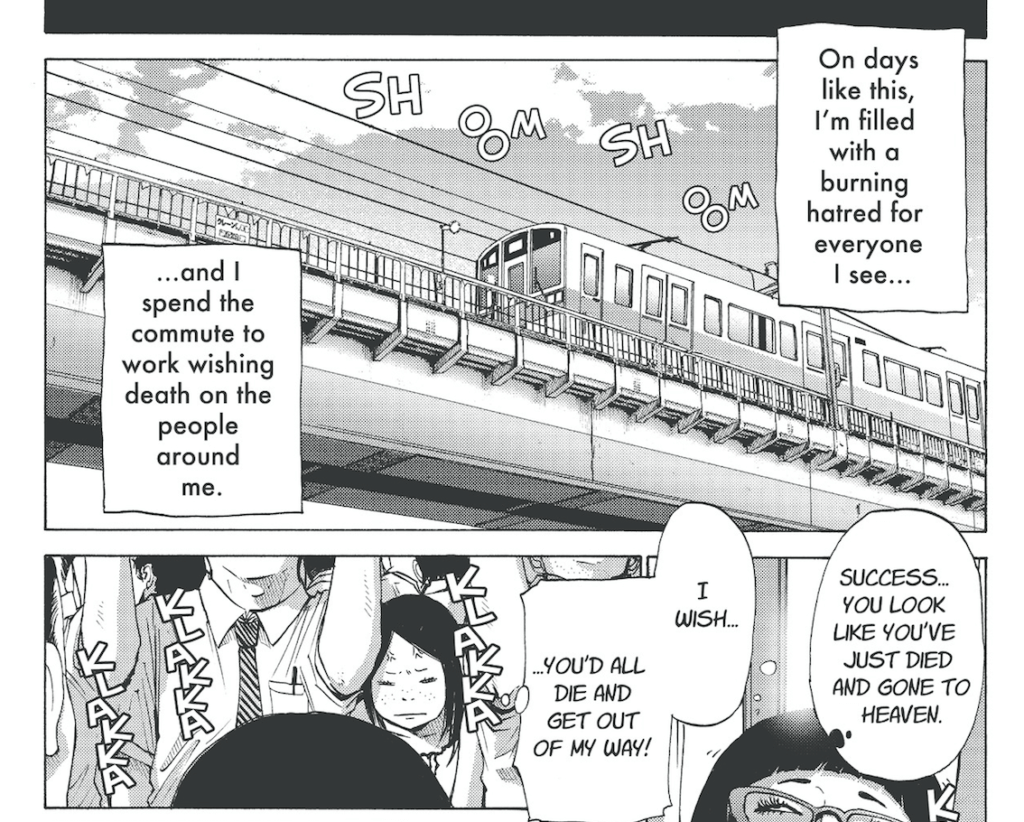

Part of the reason this manga excels is how natural the characters feel. Meiko, the main protagonist, is very relatable. She’s an office worker awaiting her special epiphany. She’s dissatisfied with society, fed up with adults, and hates how her job, her boss, and her co-workers make her feel. She never thought things would get to where they are, but unfortunately, they have, and she wishes for new opportunities to get things right.

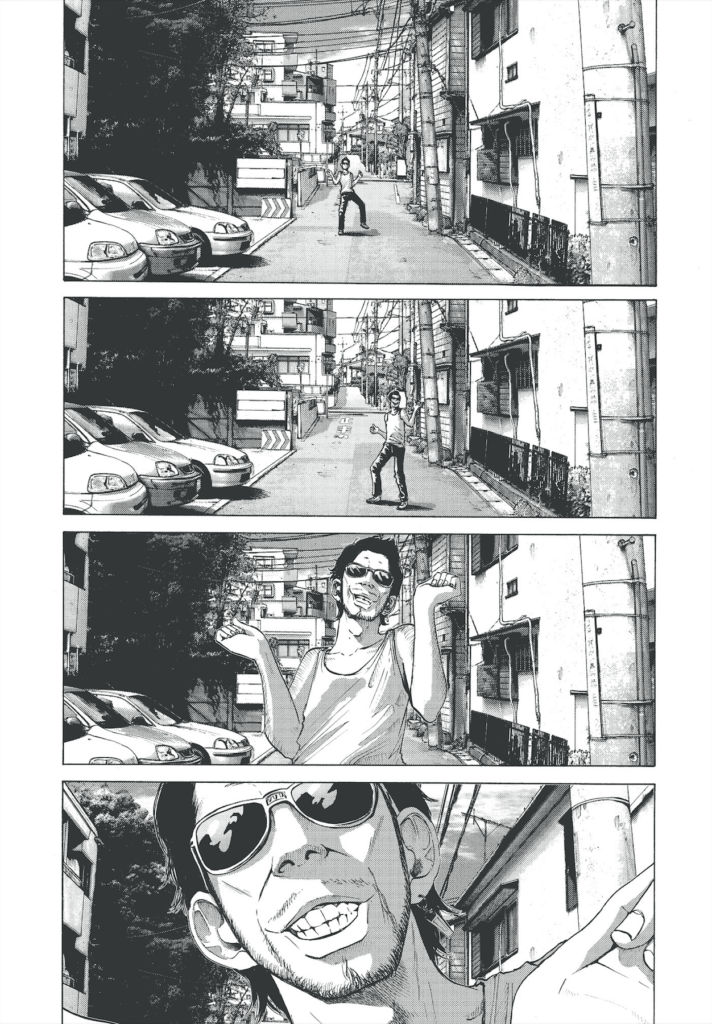

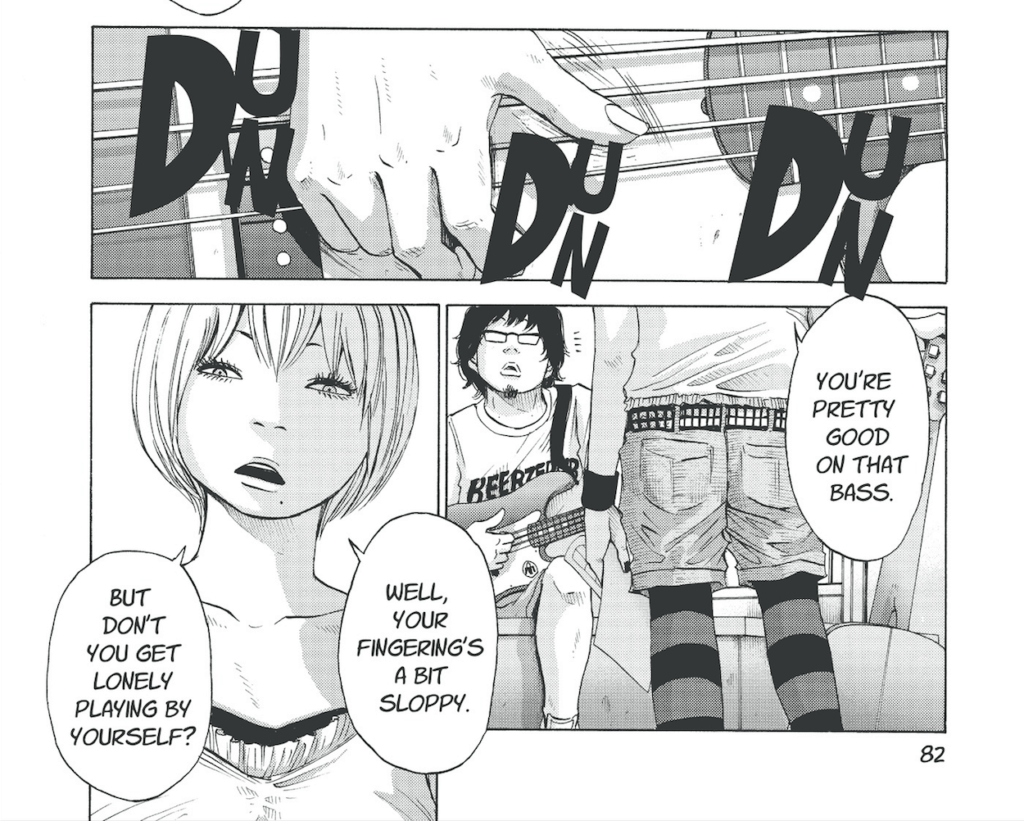

Meiko’s character feels real, and there is a reason for that. A lot of Solanin is inspired by Asano’s real life at the time. He has stated that Meiko is based on a girlfriend he had at the time of writing the story. Taneda, Meiko’s boyfriend, is the same age that he was at the time (early twenties). Like Taneda and his friends, Asano was also in a band and still plays music from time to time, which is why you see music pop up not only in here, but also in his other works like What a Wonderful World!.

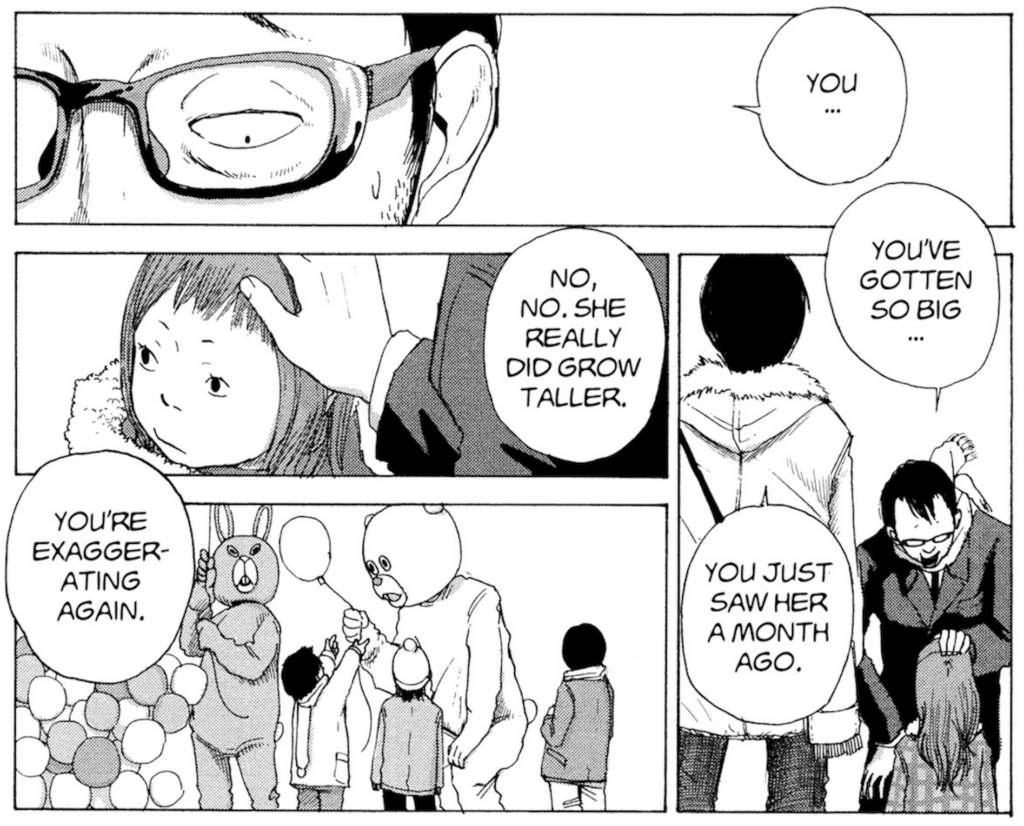

This inspired writing also explains why the dynamic between Meiko and Taneda is so powerful. The two have been together for 6 years (since their freshman year of college), and living together in Tokyo for one year. It’s the type of relationship most would be envious of, but it’s also not a perfect relationship, which makes it feel genuine. Some days, Meiko just wants to kill Taneda for some of the crap she has to deal with, but she loves him nonetheless. However, they love each other almost to a fault; In order to not stress the other out, they withhold some things, which puts an unnecessary strain on their relationship.

You can tell that several of the situations come from personal experience. With some mangaka (and anime writers), you have to wonder if they truly know how relationships work, because the medium is filled with such, quite frankly, terrible examples. But when I look at Meiko and Taneda, I can realistically see how they fell for each other.

“At the time, while I had debuted and had published work as a manga artist, my future was still uncertain. The people I was hanging around with back then were all friends I had had from college, and after graduation, we were all in a sort of “creator without a clear future” state, which made things fun from day to day, but also brought on a lot of anxiety. I put those feelings directly onto the page.” – Asano

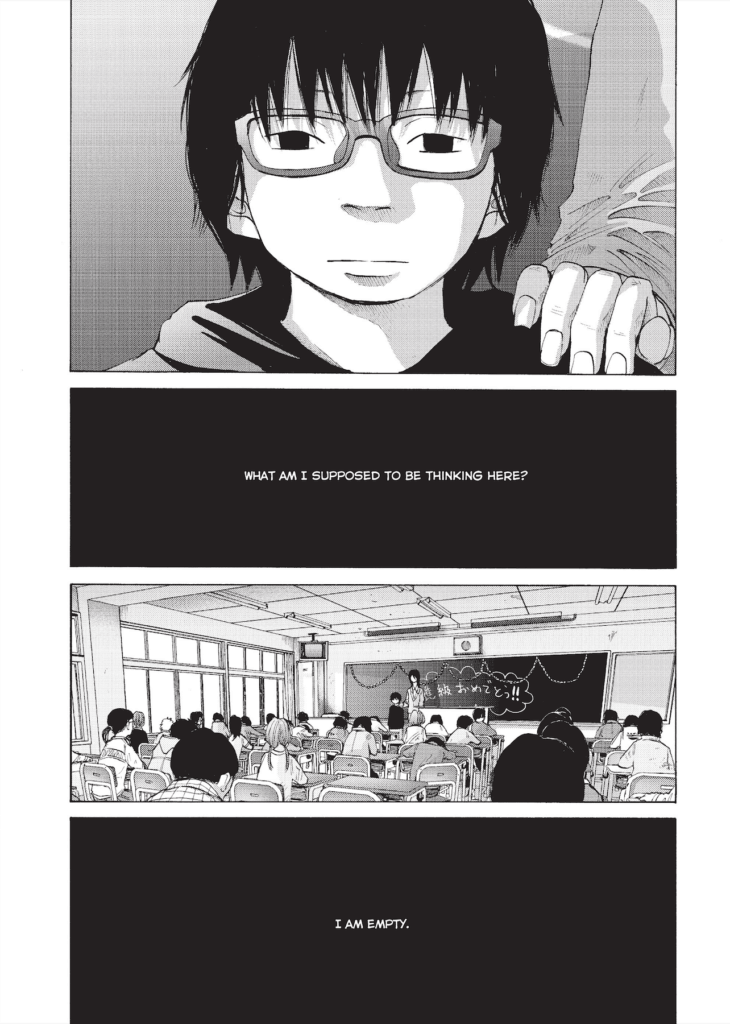

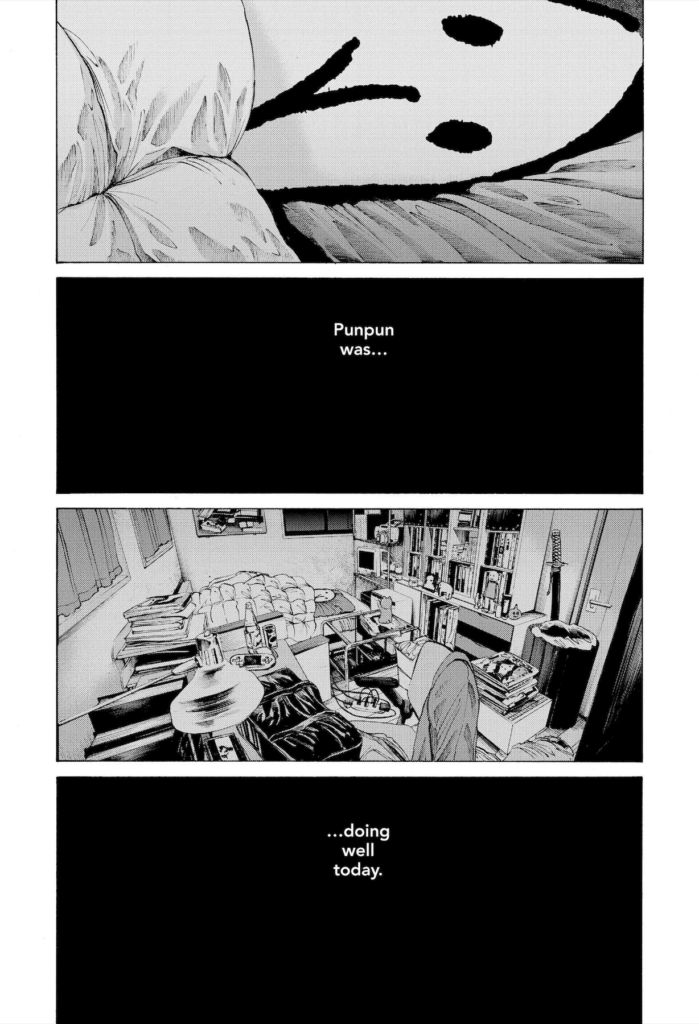

“Goodnight Punpun” (2007 – 2013)

“After I finished Solanin, when my editor started asking me what kind of manga I’d be doing next, what I always told him was that I was finished with feel-good stories.” – Asano

He wasn’t lying. Welcome to Goodnight Punpun.

Spanning 13 volumes (or 7 omnibuses for the English Viz release), Goodnight Punpun is Asano’s longest-running title to date. Staying true to his word, it’s definitely his most emotionally harrowing, as it explores several stages of its tortured characters’ lives in modern-day Japan.

If you’re drawn in by the cute little bird-shaped thing on the cover, let it be known that the cuteness ends there. Like his other works, there is hope to be found in this story, yes, but not for every character. Similarly, you’ll have to wade through some depression, abuse, self-loathing, anxiety, and more to get to it. Even then, the brief moments of respite only make the bad times feel all the more gut-wrenching.

Like Solanin, Goodnight Punpun centers on a select few characters that are more closely intertwined, with some deviation as it occasionally explores its supporting cast. However, unlike Solanin, not every character is as upbeat, and their issues are much more complex and (hopefully) not as relatable to a large group of people. Also, some characters are just plain weird (we’ll get to that later).

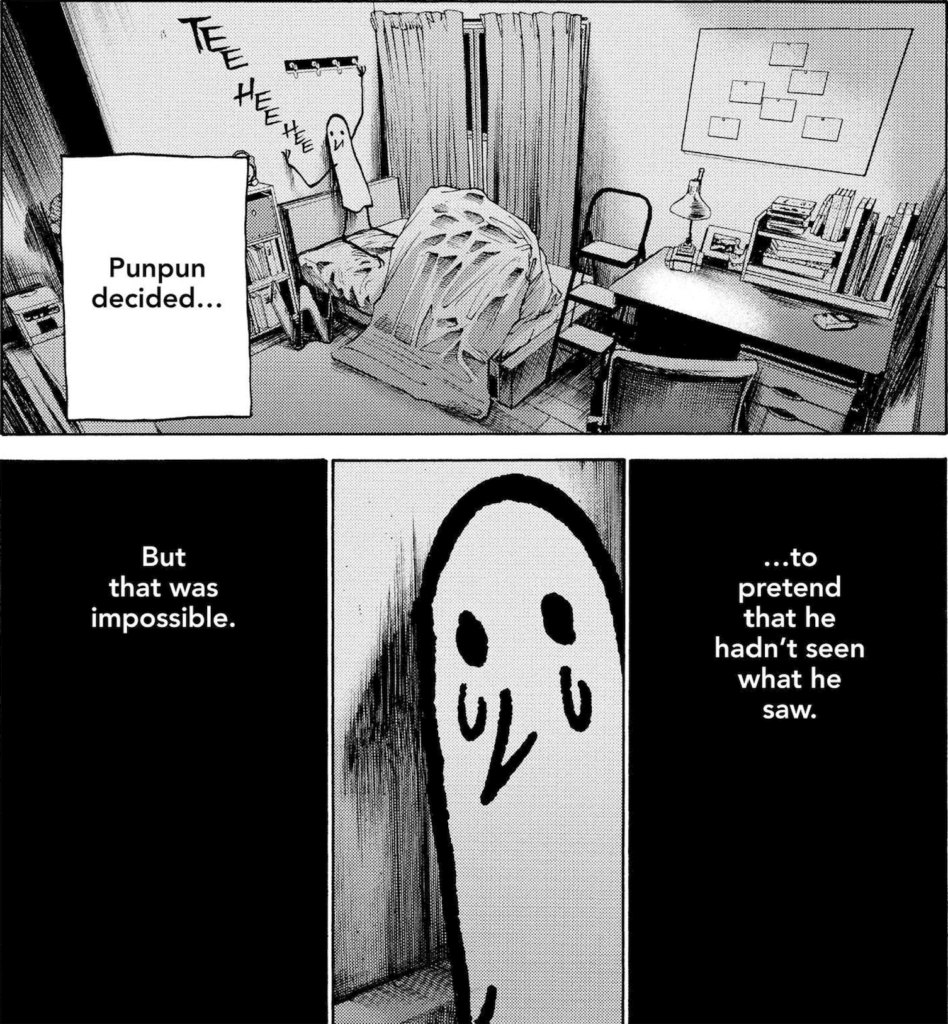

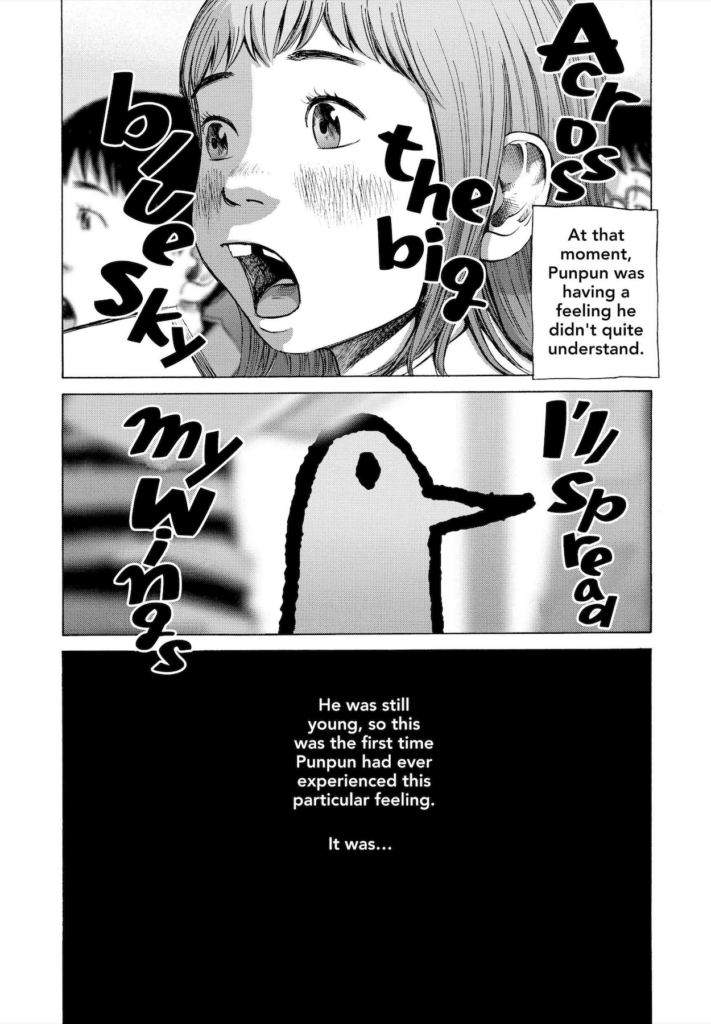

The titular Punpun is the character we see explored the most, and yes, he is that white bird-looking thing on the cover. At first glance, you might think his design would be counterproductive in telling a realistic story like Asano is known for, but you’d be surprised. As you watch Punpun experience his first crush, dream about the future, distance himself from his family and friends, and fall into depression and insecurity, you’ll find that he feels just as real as any other character Asano has written, if not more.

Goodnight Punpun is a result of Asano not wanting to be type-casted as a “feel-good” author. The manga also served as an outlet for Asano to express many of his thoughts, fears, and doubts at the time. He intentionally put scenes in the manga as a direct dialogue to his readers and the manga industry in general. With Punpun, he really wanted to destroy expectations. He even admits to ignoring the readers’ wishes at the time. Asano wasn’t trying to create a largely accessible work, like he did with Solanin. He had a very specific story he wanted to tell and he told it, as much as it angered some of his editors and readers.

Later, he’d feel slightly guilty for alienating a lot of his readers, because, as a creator, he wanted them to stick with the story to the end. However, he experienced a significant drop in sales after each dark turn in the story. After re-reading Punpun himself, he actually admitted to how messed up of a story he created, and couldn’t blame the people who dropped it. But this was the type of story he wanted to create, so he did.

Asano stated that part of the reason Punpun is drawn as a bird is to give off the impression that this is a simple manga. He wanted to pull readers in and then shock and upset them.

“People will start reading it thinking that it’s some light lecture, and then they discover that actually, Goodnight Punpun goes much further than that.” – Asano

Much, much farther. Some scenes we so unpleasant, many Japanese readers were labeling it an “utsumanga” or “depressing manga” during its release. Initially, Asano was nervous about having that kind of label slapped on his work. However, he realized some of the people saying this were still reading and enjoying it, and utsumanga was being accepted as simply another form of entertainment. To some, anyway.

Goodnight Punpun touches on things most readers will be uncomfortable with. Again, Asano purposely wanted to shock readers. He had originally planned for Punpun to be 7 volumes, but because he knew how the story was going to end, he wanted to make sure he gave the necessary time and care to his characters, so that certain events throughout would have larger impacts and resonate more.

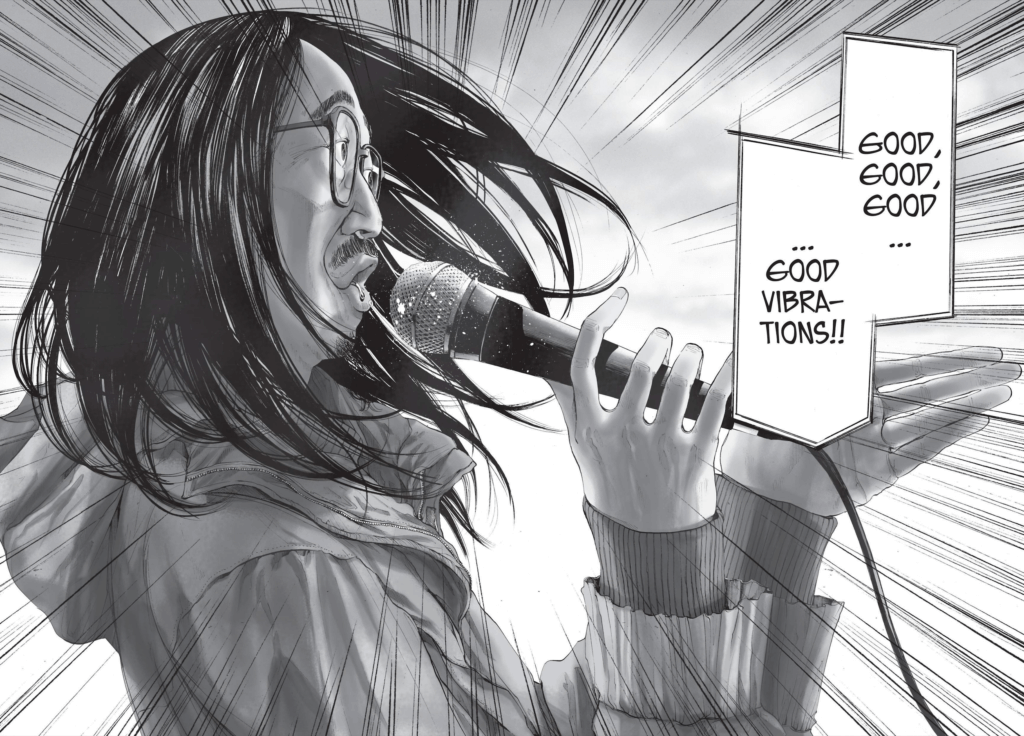

On the other end, ideas for a bunch of unplanned characters started popping up in his head too, and he felt the need to include them and expound on their stories. One of these characters is a man who calls himself Pegasus, and I have to include him in this article because, despite my personal disdain for him, Asano considers him the other main protagonist of Punpun’s story.

Pegasus is an extremely eccentric fellow who leads a super weird cult in the story. From volume 7 on, there is a whole parallel narrative around Pegasus and his cult’s existence, which ties into some key characters’ lives quite significantly. Asano considers this secondary plot just as important as Punpun’s journey.

Like some of his past works, Goodnight Punpun deals with the end of the world theme a ton, and Pegasus and his cult are a big part of that. Initially, I thought that Pegasus’ dialogue and some imagery in later chapters was mostly symbolic, but Asano has confirmed that most of what was happening was literal, and he knew a lot of readers would not be able to make sense of it. I won’t go into details here, because it would be spoiler-y, but the reality was quite the reveal for me.

Regardless of the Pegasus b-plot, the heart of the story is still Punpun. And Punpun is a character you’ll either empathize with on some level or be infuriated by. He’s not hopeless, but as the story moves on you begin to hope less for his character. He’s a really sensitive kid that has to put up with a lot of crap. Sadly, he doesn’t make things easy for himself, as he is easily swayed by the things around him. He is driven a lot by his emotions and his primal brain, so he makes a ton of poor decisions throughout the story. Asano admits that he doesn’t believe Punpun is ever in the right, and does not condone his actions in the story.

The manga is filled with characters like this. I barely scratched the surface with this section of the article, but the gist is that Goodnight Punpun is a story about the lives of unhappy people who are either mentally ill or morally gray. It’s about love and hate, life and death, promises and regrets, and all of the little nuances in between. Tread with cautious optimism or just straight up caution.

“A Girl on the Shore” (2009 – 2013)

Asano says that if Goodnight Punpun was drawn based on impulse, A Girl on the Shore is about him “regaining his balance.” He expected some people to be annoyed by Punpun, so with Shore, he wanted to provide a story that was a little more satisfying from a reading perspective (y’know, not so intentionally trolling).

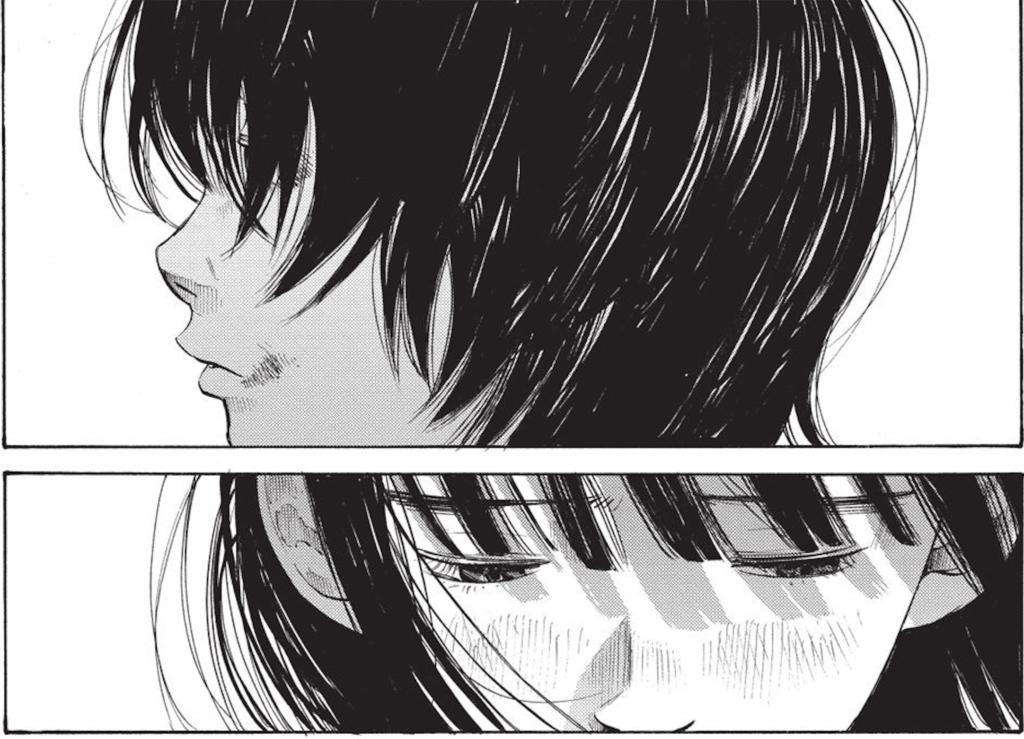

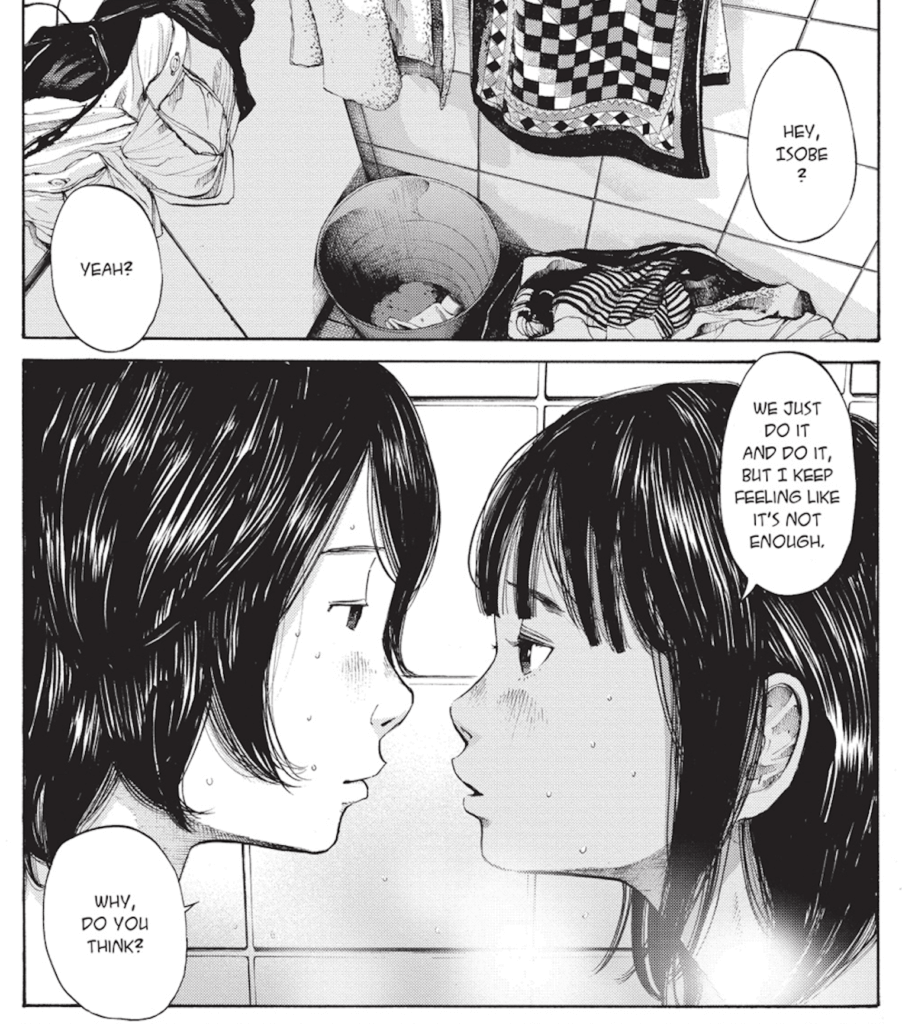

If Goodnight Punpun left me emotionally exhausted, then A Girl on the Shore left me feeling isolated and numb. And that’s because the couple that you follow in this story give off those same feelings. They’re empty and trying to find something long-lasting in a thing that only provides temporary pleasure: sex. For them, it’s what brings out any sort of emotions, but once that ecstasy dissipates, they’re left just as hollow as they were when they began. And yet they repeat the process again, and again, and again…

“At first I’d intended to make it a very innocent love story about a couple of kids in their early teens, but as I was making the rough draft, I just couldn’t get a handle on the story, so I decided to make it a love story in reverse.” – Asano

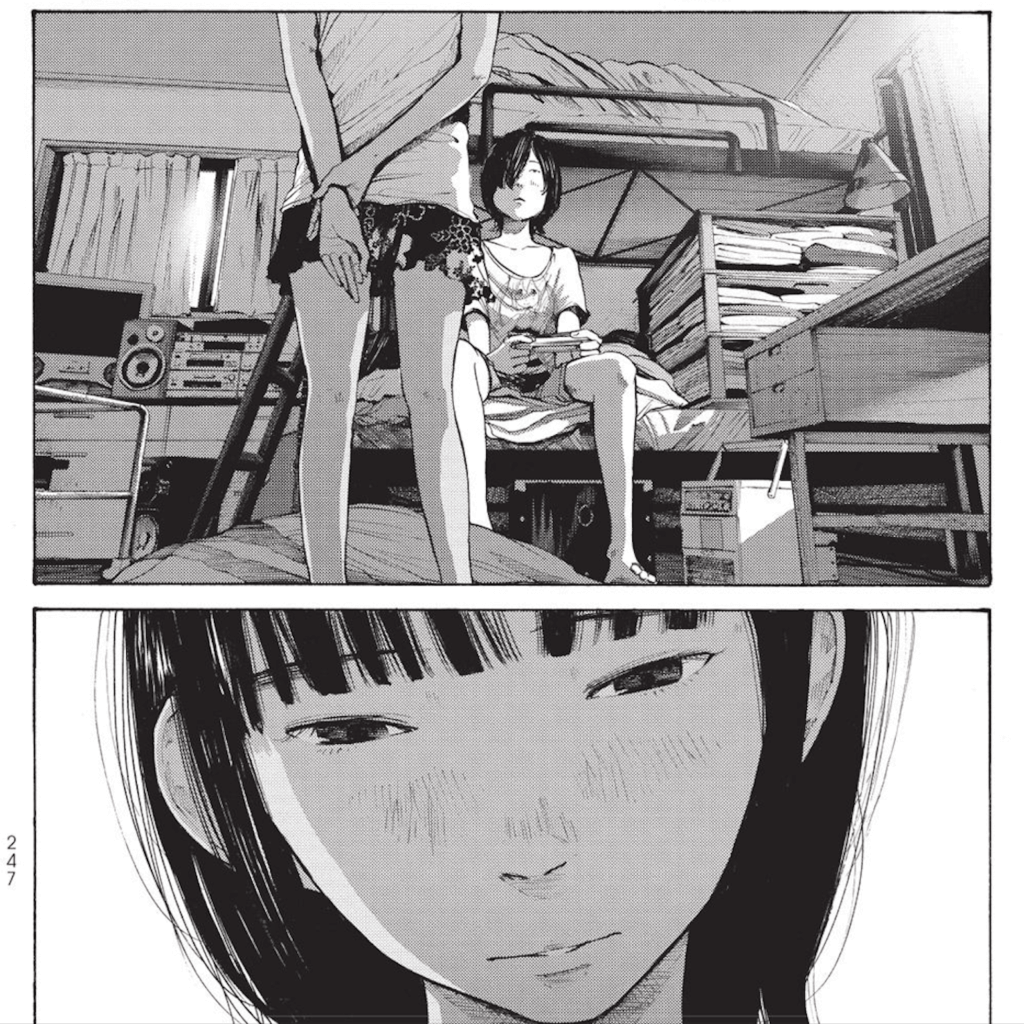

In other words, a love story about two highly dysfunctional teens who continue to selfishly use each other, because it’s the only sense of normalcy and consistency that they have in their lives. Unlike the innocent love story that Asano initially wanted to go for, he ended up crafting another story about depression, teen sexuality, suicide, and heartbreak.

“But wait, John, did you just say teen sexuality?” Yes. I have to establish that there is a lot of uncensored sex in this manga, and it is between younger teenagers. If you didn’t like what was going on in other manga like say, Scum’s Wish, this goes a bit farther than that. In some cases, but not all, it even goes farther than Goodnight Punpun.

That said, this isn’t a hentai and the sex isn’t for titillation; there is narrative purpose for it in this manga. For example: when simple, brief, casual sex no longer satisfies, the characters do it more frequently, and experiment with different locations, positions, and methods. It’s like a drug addict forever trying to achieve that next-level high. You can be dismissive and say it’s Asano being weird or pervy, but I’d have to argue and say that simply isn’t true.

On that subject, Asano gets a lot of flak for the sex in his manga. He has said so himself. However, he has expressed many times that sex is a normal part of life, and he wants to make sure it appears just as naturally in his manga.

“What bothers me is the question of why you can’t put sex scenes in a normal manga, since it’s the most normal thing in the world. But that’s why I think it’s going to be harder and harder to put those scenes in my manga, because editors and readers don’t expect or don’t want to find some kinds of content in a story when they think it’s going to be something different.” – Asano

That is a very huge double-standard, not just in the manga industry, but in life in general, and one which Asano has always tried to contest with his work. The unfortunate reality is that, despite trying to create a more satisfying story with A Girl on the Shore, he may have sadly done the opposite, and alienated even more readers due to the subject material. It truly is an uphill battle…

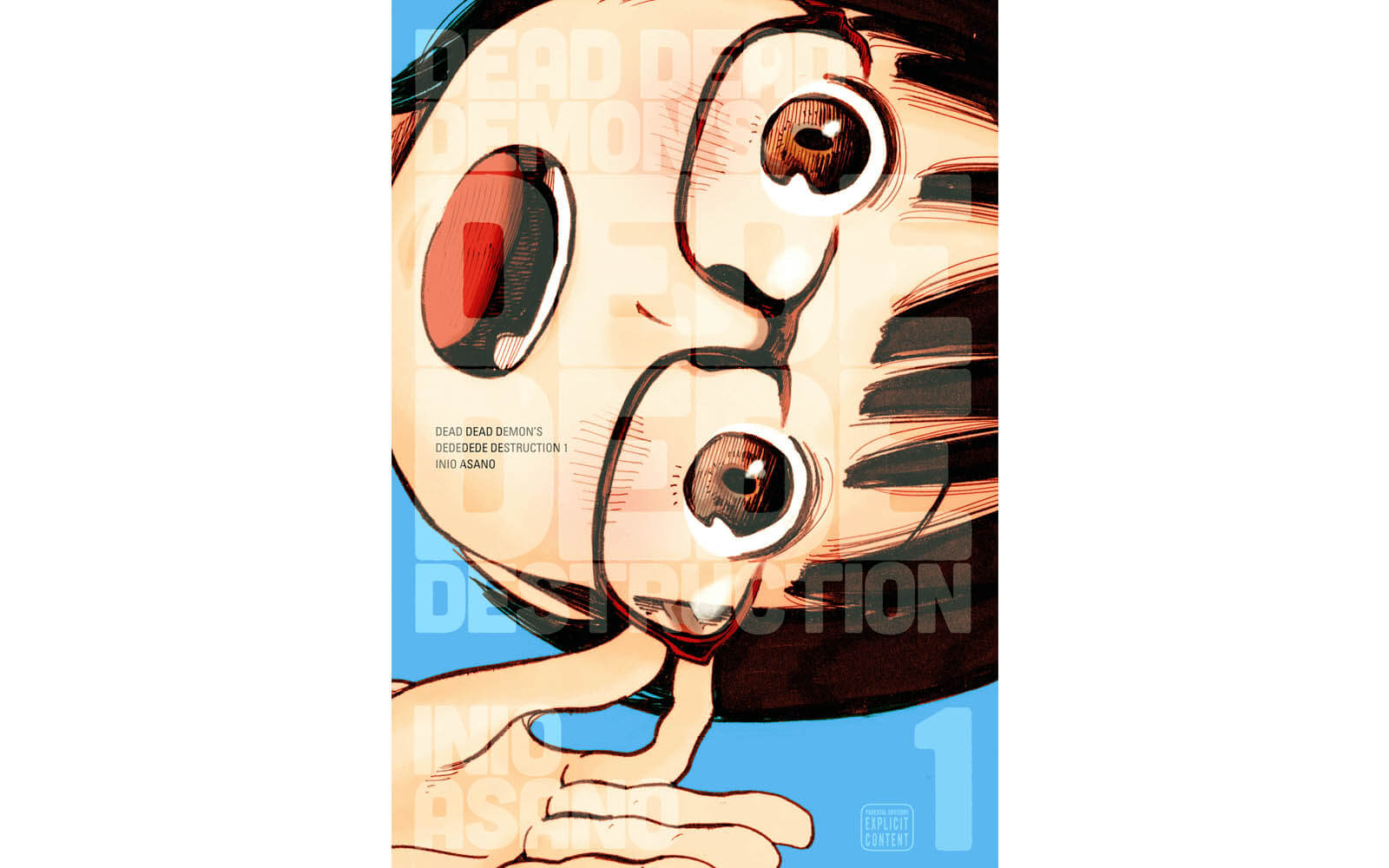

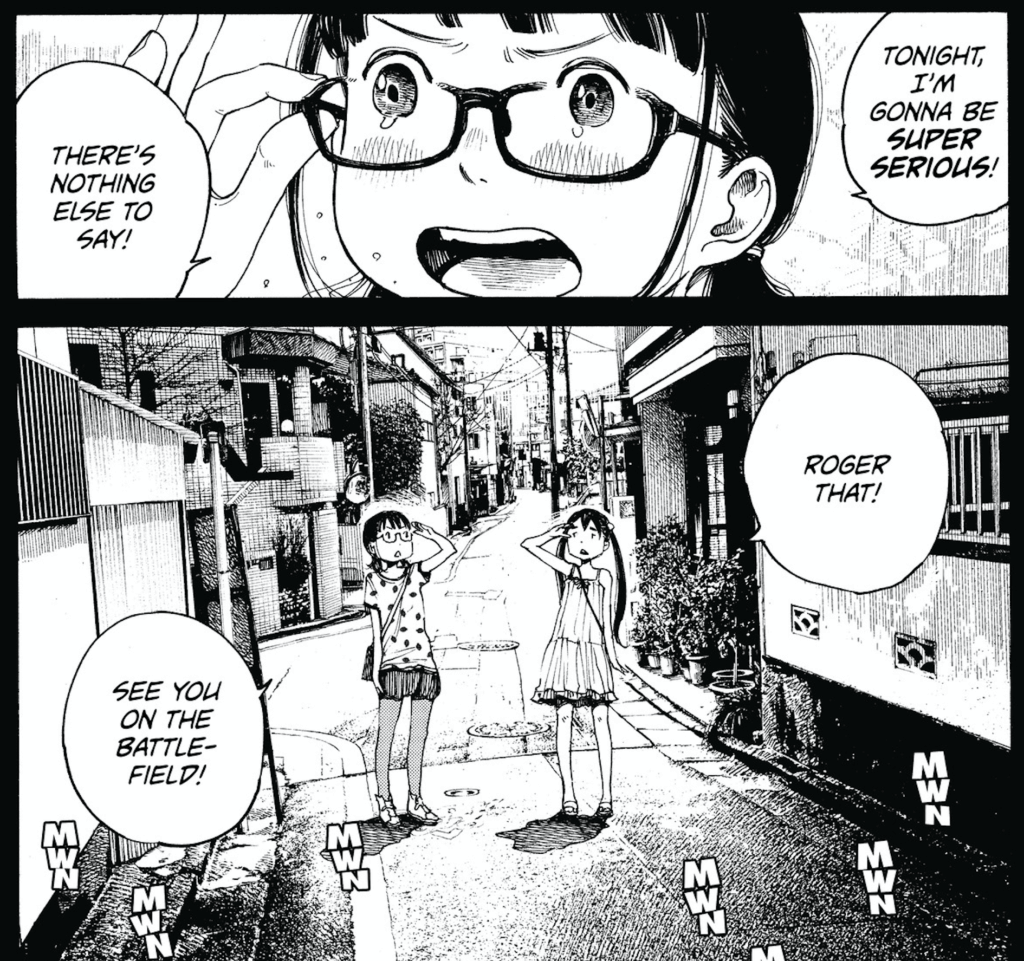

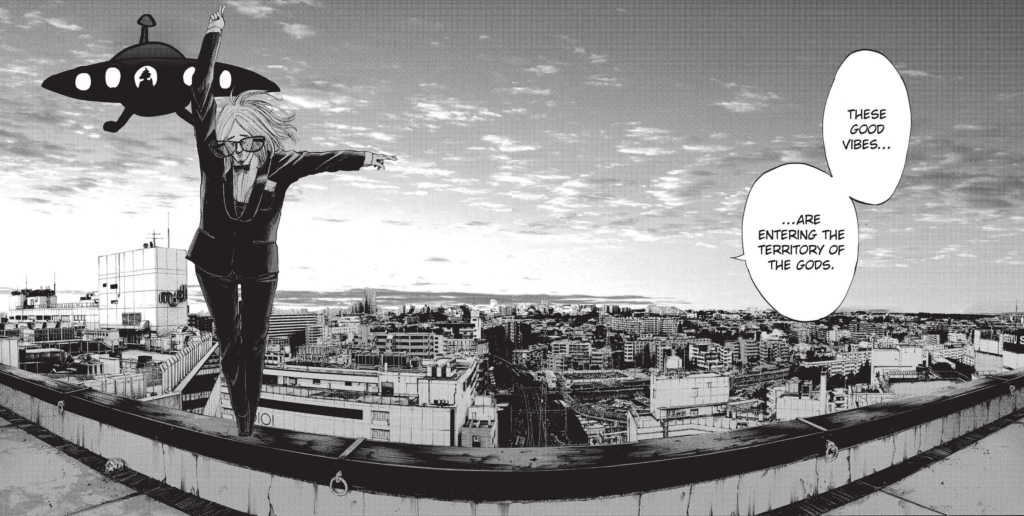

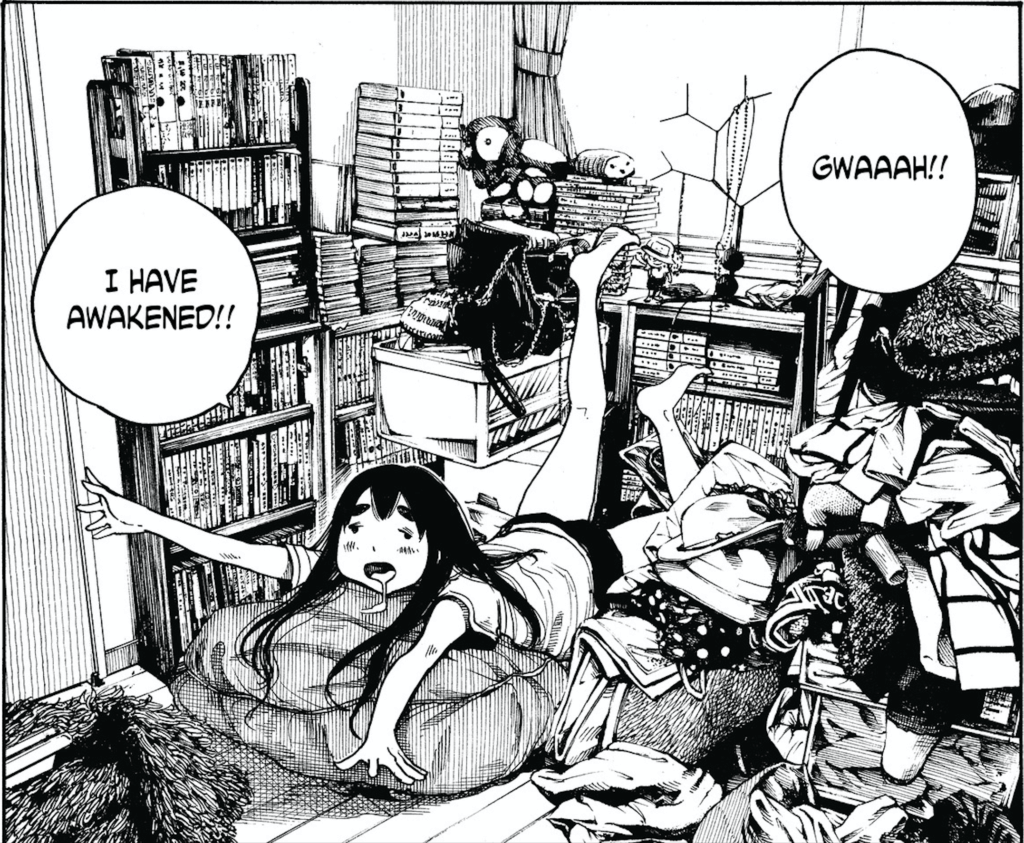

“Dead Dead Demon’s Dededededestruction” (2014 – ?)

…An uphill battle that he just might be tired of engaging in. Dead Dead Demon’s Dededoopedywhutnow, is a big shift in direction for Asano, and one that he seems to have put a lot of thought in, which I imagine is based on the reception to some of his previous manga. Asano has experienced his fair share of criticisms and, you guessed it, death threats. With Demon’s Destruction, he has said that he wants to make a manga “impervious to criticism”, even though he knows that’s not possible.

Demon’s Destruction has only recently been licensed in English and not much of the story is out there in the wild, so I’m going to keep the plot/theme details to a minimum. However, there is a ton of significance behind this manga for Asano’s career, and plenty of details from interviews that I can still share here.

Asano is always striving for something different. With Punpun, he purposely decided on a story that was “dark” or cruel, partly because he felt it was a niche that needed filling. He thinks that pessimistic works where the main characters find no redemption are encouraging. He enjoys the fact that works like that exist, but with Demon’s Destruction, he’s tackling things from a different perspective.

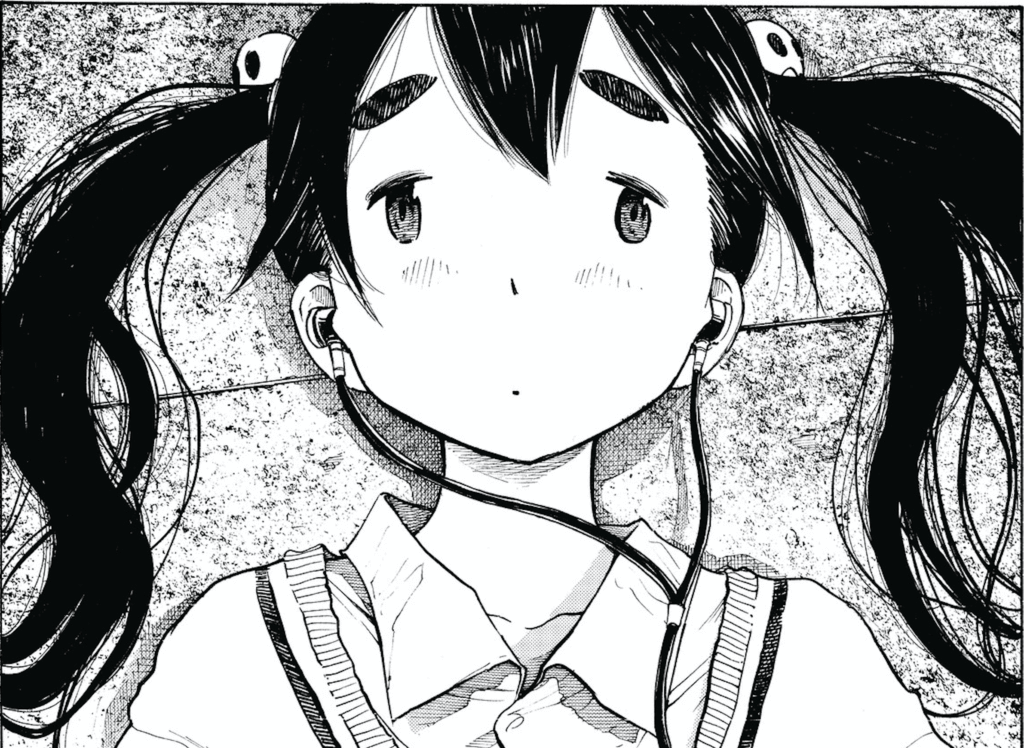

His purposeful shift to a more “moe” design is part of this new perspective. Doing research for this article, I’ve noticed that Asano alludes a lot to the fact in interviews that he’d like his manga to sell way more than it has been. This is his career, after all. The “moe-fication” that he’s going for here definitely stems from some pressure from the Japanese market. Asano has noticed Japanese readers often don’t like difficult stories, so he’s trying to lure more of them in by making his designs more eye-catching.

“It’s not so much as draw something that’s good and it will sell. Now it’s more like ‘Do what the market likes and you’ll sell!’” – Asano

He seems to not mind changing up his style in this manner, if it means he can encourage more people to read his manga and not get rejected right out of the gate. Plus, it’s given him the opportunity to draw in ways he was never able to draw before, due to the tone and nature of this work compared to his past ones.

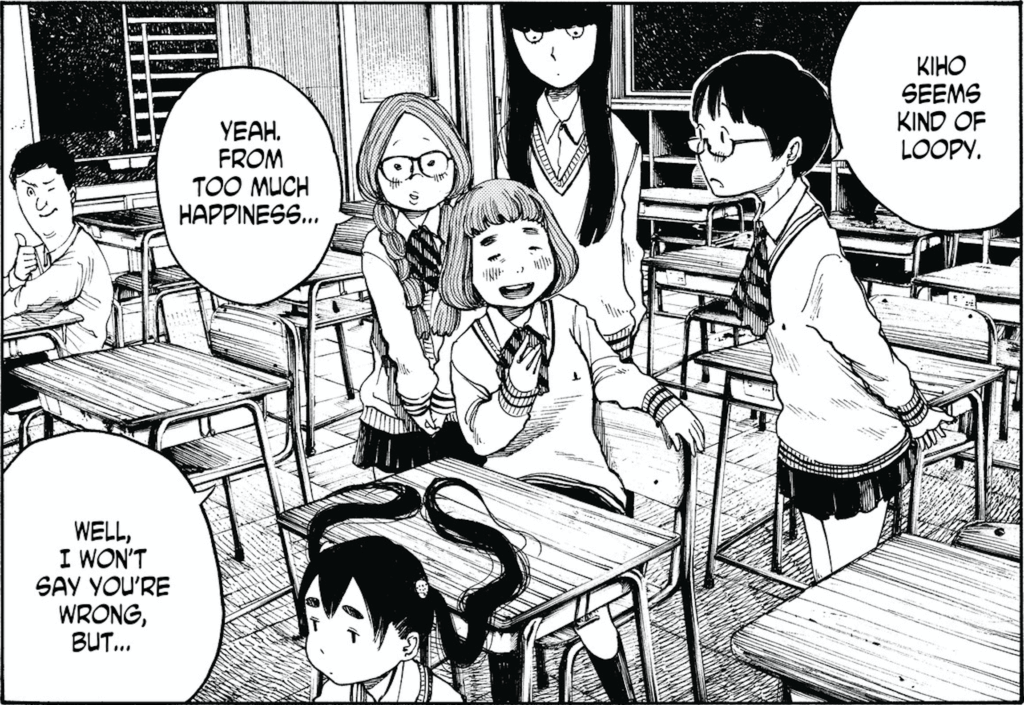

Another step Asano is taking with this manga is to be less preachy than in his previous work. In fact, he’s tired of it:

“I really like to put my own thoughts and opinions in my manga. Up until Punpun, all my manga was absolutely chock full of scenes where I’m just talking about myself, or these dialogues where characters go back and forth just to show how right my opinions are. I’ve had enough of that stuff. I just want my characters to say whatever silly things they want, living in whatever silly way they want.”

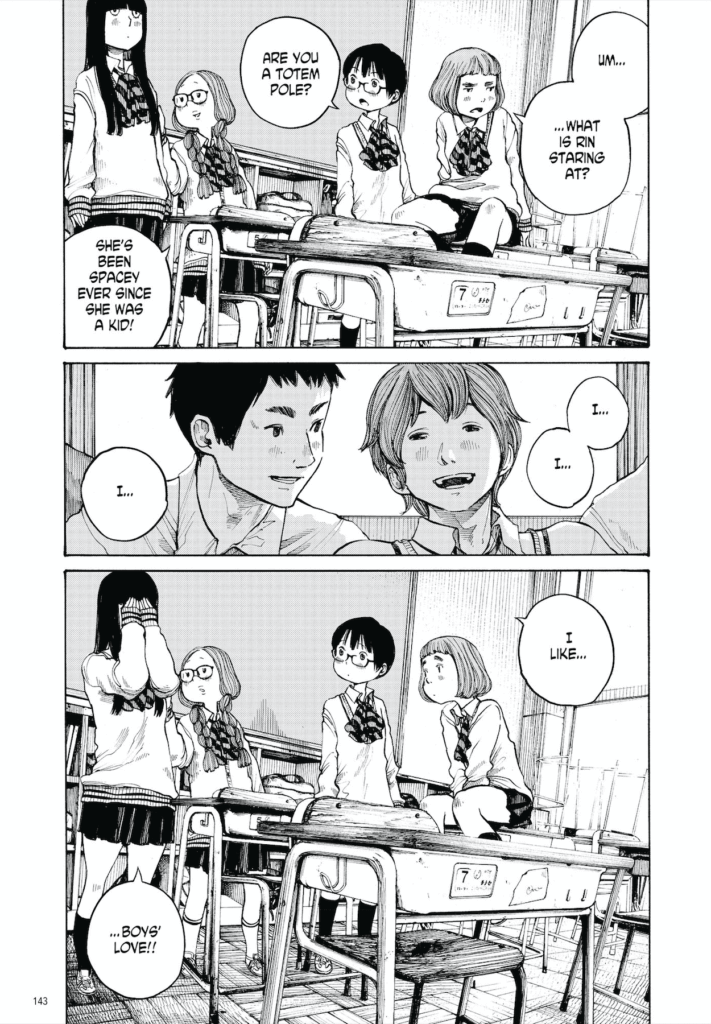

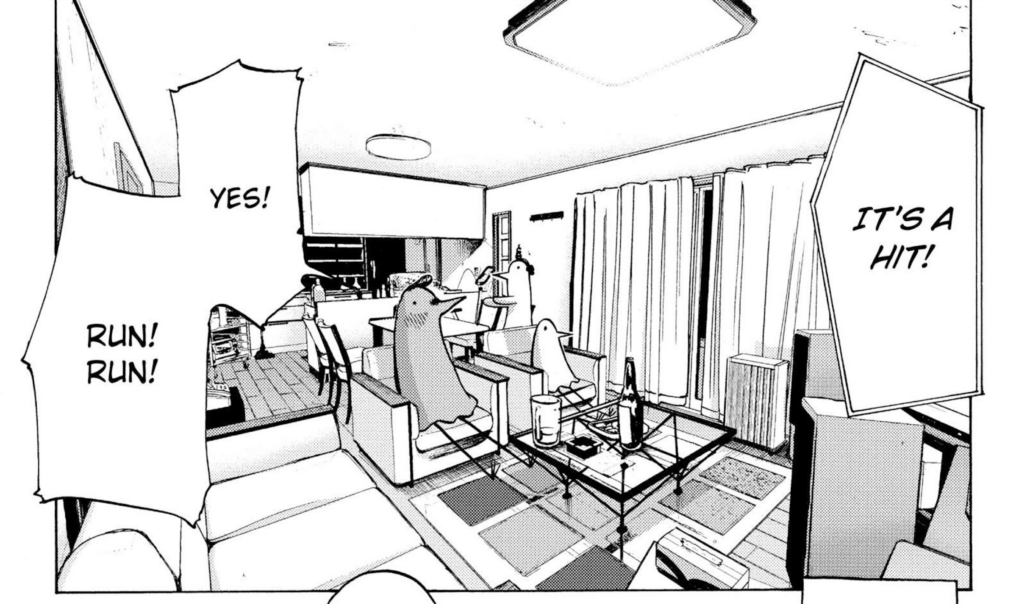

And that’s exactly what his characters do in Demon’s Destruction. It’s a story about two high school best friends’ silly antics in their everyday life… three years after a massive alien mothership appeared before Japan. While there are some crazy things going on behind the scenes, the overall tone is relaxed and comedic, which really hasn’t been the case since Solanin.

“I’d been thinking about what to do for my next series since a year or two before Punpun ended. This manga is the result of taking a bunch of ideas I’d had and sticking them together almost like a jigsaw puzzle, so it’s difficult to explain exactly how it came to be what it is. I originally wanted to do a manga with some creature living at the protagonist’s house, like Doraemon; the manga at the start of the first chapter is a vestige from that.”

But that would’ve been too normal for Asano, so he opted for creatures invading from outer space instead.

Lastly, Asano is worried about the fate of Seinen magazines. After all, Punpun started in a magazine called Young Sunday, but that ended up going under, so it had to continue its run in Big Comic Spirits, where Demon’s Destruction is currently releasing in.

“There are all kinds of seinen magazines out there — for example, you’ve got the Kadokawa and Square Enix ones, which I think of as manga made by manga enthusiasts, for manga enthusiasts. It’s a specialized kind of entertainment. The general seinen magazines, on the other hand, deal with subject matter that’s actually connected to society, so you don’t have to be a manga enthusiast to enjoy them. I really do like the manga Shogakukan [the publisher of Spirits] puts out.”

He doesn’t want to lose Spirits, so I think he feels the need to create something more accessible again, kind of like he did with Solanin. After reading the first volume, it certainly looks like he’s treading along in that direction. If he continues in this way, I imagine Dead Dead Demon’s Destruction will stay appealing to a wider audience and have the potential to emulate Solanin’s success. No doubt that would contribute to boosting the magazine it’s a part of, putting some of Asano’s fears about losing Spirits to rest. Dead Dead Demon’s Dededededestruction is currently ongoing, so only time will tell.

The Evolution of Asano’s Art:

First of all, if you made it this far, thank you for reading! We’re in the final stretch here, so I hope you can hold out a little longer. I wanted to close out by talking about the evolution of Asano’s art between his works. After all, I can’t talk about a mangaka without addressing such a vital aspect of their work!

In What a Wonderful World!, Asano only just started using the computer to assist in his drawing. I believe at the time, he started developing a technique with Photoshop for backgrounds specifically (more on that later). Other backgrounds may have been traced from photographs. World! is a little different from Asano’s later works, as he does sometimes omit backgrounds entirely from some of his panels, which you rarely see from him in his more recent works. Another thing I noticed is that characters aren’t as detailed as they end up being in his later series. There is also a very sparse usage of 2-page spreads.

In Nijigahara Holograph, it’s the complete opposite. Everything is hyper-detailed and very much in line with his more recent offerings. The way things are framed is reminiscent of a film. It’s clear he’s gone more digital with his backgrounds and it’s very rare to see a panel without one. Digital filters are added over certain things, like a glow on the butterflies that are featured so prominently in the story. This makes the butterflies more ominous whenever they appear on a page. Asano also adds the concept of focus/blur to some shots, which you can’t effectively communicate through analog. Lots of extra details like this really make the pages pop.

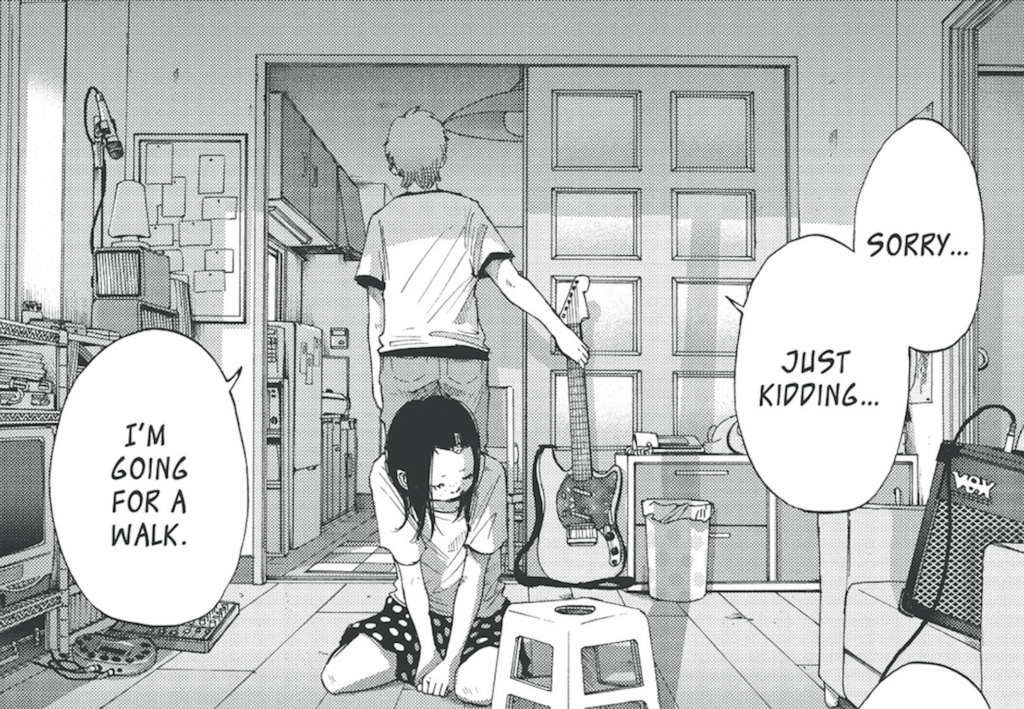

On the art front, Solanin is a blend of both of his previous works, in terms of style. It’s clear his artwork has improved, like in Holograph, but because of the tone of Solanin, he’s not afraid to leave some backgrounds more minimalistic, as some were in World!. And while his characters never go full-on chibi, occasionally their facial characteristics will devolve to add humor to a scene, or to accomplish a specific type of reaction.

One thing I noticed is that Asano is really good at making his characters ugly cry or make unattractive expressions in general. He’s also not afraid to design conventionally unattractive characters. Asano says himself that he purposely drew Meiko with freckles because he didn’t want to draw a conventionally pretty girl (for the record, I think she’s still super cute). The diversity and realism in his character designs makes his stories all the more enveloping.

With Goodnight Punpun, Asano returns to the more hyper-realistic style that he had in Holograph. It’s an improvement on many levels, but a few things that stood out are the backgrounds and digital effects. One of the many reasons Asano drew the character Punpun like a bird was so that he could flesh out other details of the manga, like the backgrounds. “(If) I can draw the main character in 5 seconds, I can spend more time on the other stuff, right? (Laughs).”

Early in his career, he received criticisms on his backgrounds, so he’s been experimenting with a digital+analog technique ever since.

“If you googled ‘Inio Asano’ back when my first volume came out [talking about works before What a Wonderful World!], you’d only get six results, and one of them described me as being ‘just awful at backgrounds’, which I really hated, so I started trying all sorts of different methods. There’s a part in Dennou Manga Giken [a collection of manga artist interviews regarding how they use computers in their work] where it says Usamaru Furuya printed photographs in light blue and traced them, so I tried doing exactly that myself, for example.” – Asano

And his technique has evolved since that quote. If you wondered how his backgrounds could be so photorealistic, it’s because they’ve literally come from photos. Asano takes a few times out of the year to capture hundreds of photos for reference. He then selects a photo that will fit the angle and the scene, adjusts it to a monochrome setting, arranges it, removes the mid-ranges, and messes with the levels until it starts to resemble a drawing. He’ll then print it out and begin fixing up the image, adding his own texturing. After that, he continues to add things like shadows and (manual) screen tones on the computer for finishing touches.

“If the only thing I did was Photoshop it, it wouldn’t really feel right, so I muck up the spots that stand out on purpose for that rough feeling that analog has.” – Asano, in a video interview with Naoki Urasawa (Monster, 20th Century Boys).

This is a technique he has developed for over 10 years, and it’s not something you see replicated often by another mangaka. Asano says that it’s still a ton of work and he sometimes wonders if doing all of his backgrounds analog would be quicker and easier.

One last note, in reference to Punpun’s design, Asano initially wanted all of the characters in the manga to look that way, but his editor didn’t approve of it, so he got away with making just Punpun and his family share that design.

In A Girl on the Shore, Asano changed up locales to a more coastal region. When he draws his works, he usually starts with the backgrounds. The location and its landscapes are starting points for his manga’s production. For instance, he decides what kind of characters his story is going to have based on where they live and what district they’re a part of. In Shore, he thought it would be easier to set it on a beach, so he wouldn’t have to worry about backgrounds too much. But…

“It’s compulsive with me: I don’t feel like the manga looks finished if the backgrounds are just left blank. As the title says, it was supposed to be a manga that takes place at the beach, but I kept taking it to the city because I just can’t be satisfied without buildings in the background.”

In Dead Dead Demon’s Dededededestruction (man, I can’t get over that title…), Asano uses his Photoshop technique not only for backgrounds, but also for all sorts of objects. For instance, he uses an ashtray and wooden fish block as bases for drawing some of the spaceships that appear in the story. Asano is very free thinking when it comes to these designs and doesn’t adhere to established sci-fi concepts.

He takes advantage of these digital methods to accomplish something that would take a crazy amount of time to do from scratch. It’s not all copy and pasting though. In a video interview, he mentioned he still spends hours making adjustments to a two-page spread, adding in all sort of details, big and small.

That said, with Demon’s Destruction, part of the iteration of his digital-analog style is to not rely as much on the digital aspect as he did in Goodnight Punpun, for instance.

“When I’m drawing something I’ve never done before, I can’t explain it to my assistants without having ever done it myself before, so I ended up doing the fire scene [talking about an event that happens very late in Goodnight Punpun] almost all by myself. I really like working on improving my technique because you can actually visually see it getting better, but the background work for Punpun became routine, because I could already visualize the finished product once I had a photo for tracing. It’s not any fun drawing a picture that you’re already able to visualize, and I started to feel like I was ruining these pictures I’d done in pen by digitally processing them, so I really hated it. I stuck with the same method the whole way through Punpun for the sake of consistency, but my next series is going to be pretty different.” [Referring to Dead Dead Demon’s Destruction]

Just The Beginning

Dead Dead Demon’s Dededededestruction is currently ongoing in Japan, and Asano has expressed that he’s not sure when it will end. He alludes in an interview that he’d be fine if it ends up being his life’s work. If that becomes the case, I’ll still be excited to see where the manga goes, and I have faith that Asano will still tell all of the same great stories he’s known for, even if it’s contained in this one work.

Inio Asano debuted at 17 years old and, as of this post, he’s only 37. Despite his young age, he has already told so many fantastic stories throughout his career that have resonated deeply with me and his community of readers worldwide.

Though he’s been working on Demon’s Destruction, he has already written a few one-shots since its debut, that are just waiting to be licensed in English (please, VIZ-sama!).

Actually, there’s an entire backlog of his work (15 manga total) that hasn’t been licensed for English release yet! I’ve sadly only just scratched the surface of his career in this article, but I hope that through highlighting some of the major releases, you’ve felt the urge to try out at least one of Inio Asano’s manga.

You made it to the end! Subarashii! I know it was a lot, but I’m super grateful that you took the time to check this out. It was a bunch of work, so it means a ton. That said, I’m crazy enough to do it again! So, if you liked this and want to see me cover another mangaka, let me know in the comments below.

If any of these manga sounded interesting to you, you can check them out on Amazon, as follows: What a Wonderful World!, Nijigahara Holograph, Solanin, Goodnight Punpun, A Girl on the Shore, and Dead Dead Demon’s Dededededestruction.

If you’re interested in articles similar to this one, check out Astra’s Junji Ito Analysis and other mangaka featured articles on Yatta-Tachi.

Don’t forget to click on the sources below for all of the awesome, info-packed Inio Asano interviews that different people have so graciously translated into English for us.

Sources: Asano Video Interview with Naoki Urasawa (Manben), The Disaffected World of Inio Asano, A Tour Through Inio Asano’s Workspace, Inio Asano and Daisuke Igarashi On Getting Started In The Manga Industry, A Conversation Between Inio Asano and Usamaru Furuya, Inio Asano On Nijigahara and Punpun, Taiyo Matsumoto with Inio Asano and Keigo Shinzo, Asano Inio Interview – Autodesk.jp, Interview: Inio Asano (ANN), Mangaka Spotlight: Inio Asano Part 1, “Reality Is Tough, So Read This Manga About Cute Girls and Feel Better”

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page