Last June, I went to the Japan Society in Manhattan for Life of Cats, an exhibit on ukiyo-e prints that feature the adorable felines. Below are some of the prints that were on display during the second rotation of the exhibit. The exhibit was broken down into five themes: Cats and People, Cats as People, Cats versus People, Cats Transformed, and Cats and Play. Many of the prints on display were borrowed from the Hiraki Ukiyo-e Collection in Tokyo. Let’s take a look at some of the prints that were featured!

Cats and People

In the first segment of the exhibit, the prints that were on display depict the presence of cats in the lives of various Japanese people. Sometimes the cats interacting with the humans is the focus of the piece, and at other times, the image of the cat is snuck into the print.

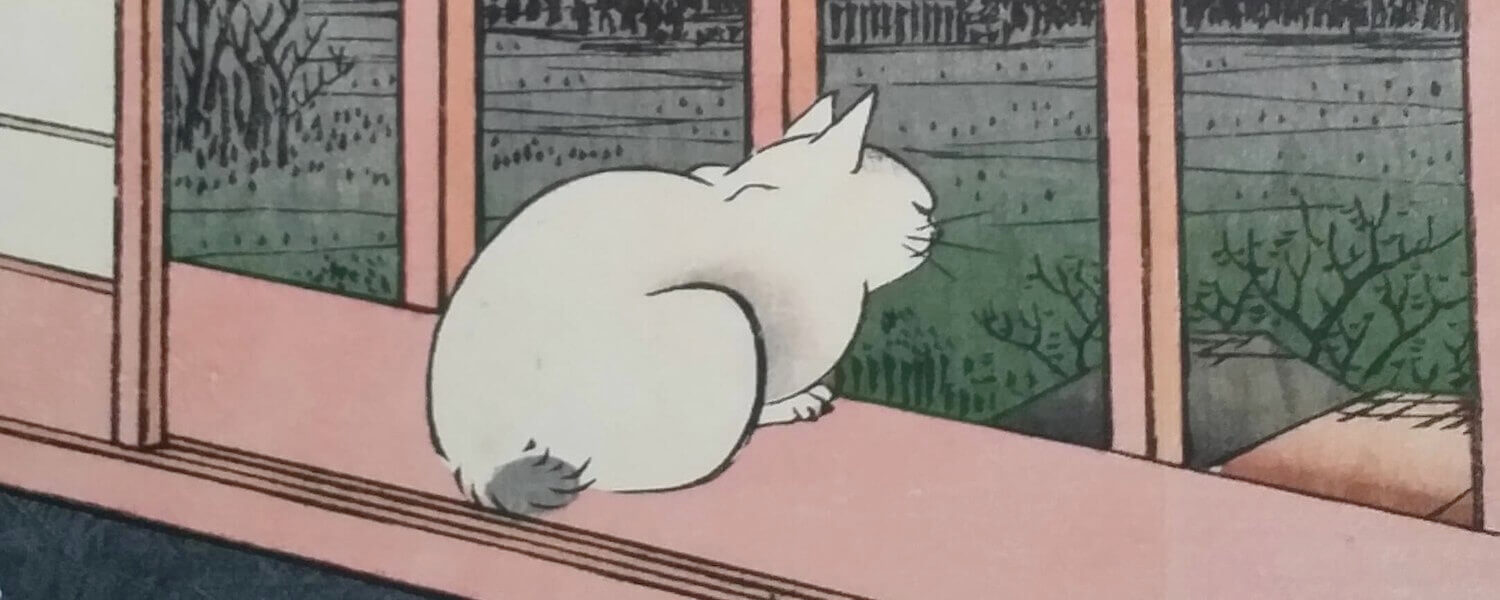

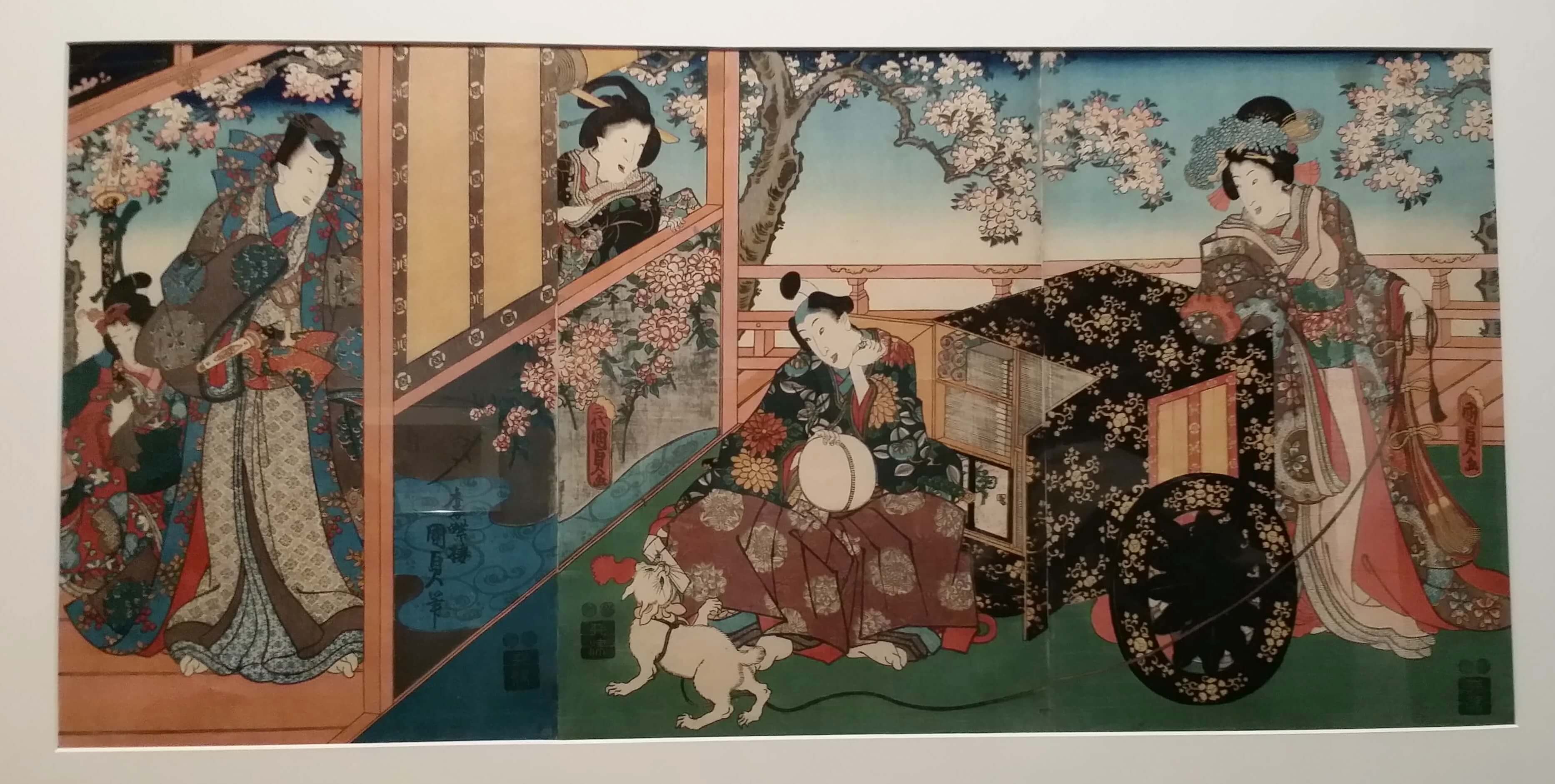

Kashiwagi from the series The False Murasaki’s Rustic Genji. Print by Utagawa Kunisada II.

The Tale of Genji, often considered the first novel ever written, has been adapted and retold in many different ways throughout history. The scene depicted in this print follows Ryūtei Tanehiko’s adaption called The False Murasaki’s Rustic Genji (Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji), which brings the setting of the story to the fifteenth-century and into the realm of the samurai. In this version, the Third Princess is shown as a seductress, giving her cat a love letter to deliver to Genji.

Restaurant Nabekin in Osaka-machi from the series An Assortment of Famous Restaurants of the Present Day. Print by Utagawa Kunisada.

The series that this print is from, An Assortment of Famous Restaurants of the Present Day, contained individual prints that each featured a famous restaurant from the time period, and it acted very much as a restaurant guide. The increase of expensive restaurants during the Bunka-Bunsei period (1804-1829) also saw an increase of guidebooks like this. This particular print was made for the Nabekin restaurant and features a woman who is possibly a geisha. They were usually called to provide entertainment for the numerous dinner parties held at such restaurants.

The series that this print is from, An Assortment of Famous Restaurants of the Present Day, contained individual prints that each featured a famous restaurant from the time period, and it acted very much as a restaurant guide. The increase of expensive restaurants during the Bunka-Bunsei period (1804-1829) also saw an increase of guidebooks like this. This particular print was made for the Nabekin restaurant and features a woman who is possibly a geisha. They were usually called to provide entertainment for the numerous dinner parties held at such restaurants.

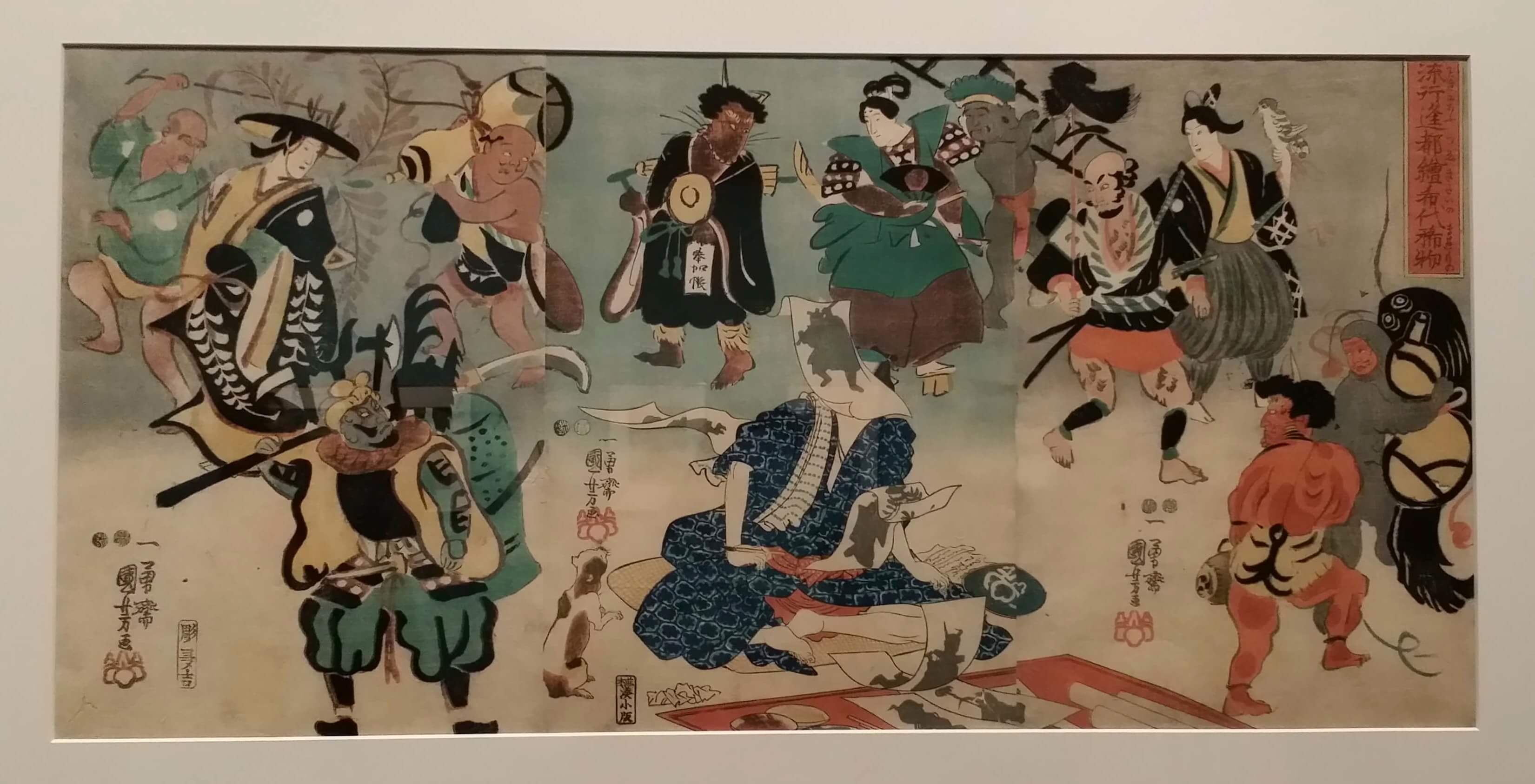

The Amazing Phenomenon of Ōtsu-e Paintings. Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

Ōtsu paintings were first made as folk art in the city of Ōtsu during the seventeenth-century and became one of the most popular souvenirs to purchase along the Tōkaidō Road linking Edo and Kyoto.This print features many characters typically depicted in Ōtsu-e works, such as oni (“goblins”) and figures from Kabuki plays. The artist of this print, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, is famous for his love of cats: his students often described him as being surrounded by them in his studio. Here, a cat is sniffing at Kuniyoshi’s paulownia seal in the middle portion of the painting.

Zen Priest Bukan from the series Sixteen Female Sennin Charming Creatures. Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

In the upper right-hand corner is an image of Fenggan (known as Bukan in Japan) with a tiger. A monk who lived during the ninth century, he was known to ride a tiger and scare his disciples. He appears in a Zen painting motif called The Four Sleepers, in which he, his tiger, and two other Zen monks are portrayed sleeping on a mountainside. This print shows him awakening from that slumber, pairing that image alongside that of a woman and her cat waking up from a nap.

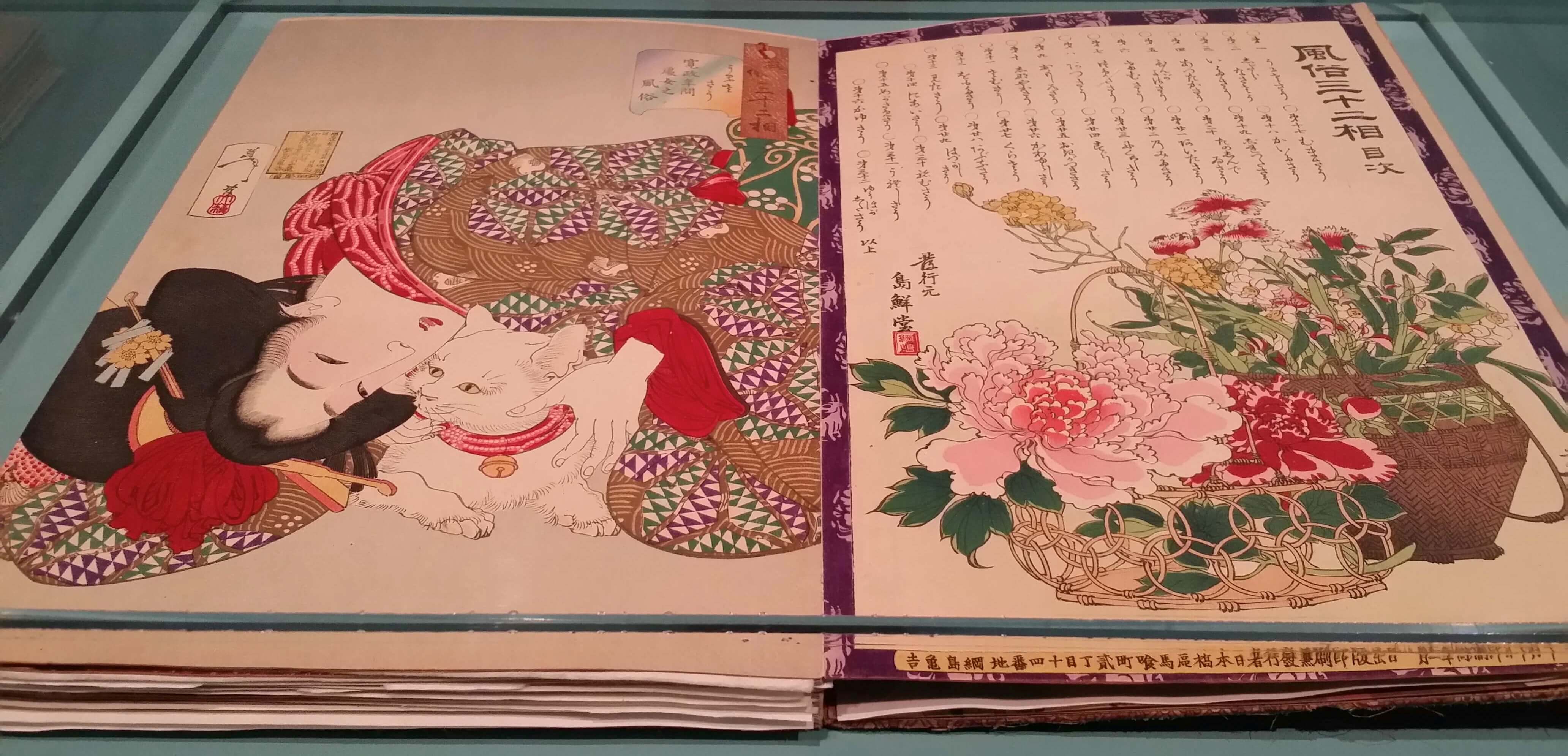

Looking Tiresome: The Appearance of a Virgin of the Kansei Era from the series Thirty-two Aspects of Customs and Manners. Print by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi.

Just like the previous prints above, this print was part of a series, as were most ukiyo-e works. While most prints are put on display individually, originally such works were kept in an album format, much like this one. Thirty-two Aspects of Customs and Manners features prints that each pertain to a different emotion portrayed by a woman as the main subject. It’s possible in this print, though, that it is actually the cat who is related to the word “tiresome”: perhaps the feline has had enough of all that cuddling from the woman.

Cats as People

The prints collected for this portion of the exhibit feature anthropomorphized cats. Many of the prints have them behaving as commoners and engaging in the activities and entertainments popular amongst them during the Edo period. Such giga (caricature) prints came about due to the many cats that wandered the streets during the time. Using caricature also allowed artists a higher degree of freedom in what they created, particularly during the Tenpō Reforms (1842-1845), which put limits on allowable entertainment. Using cats allowed the prints to pass for neko-e (“cat picture”), which were used to scare away rodents.

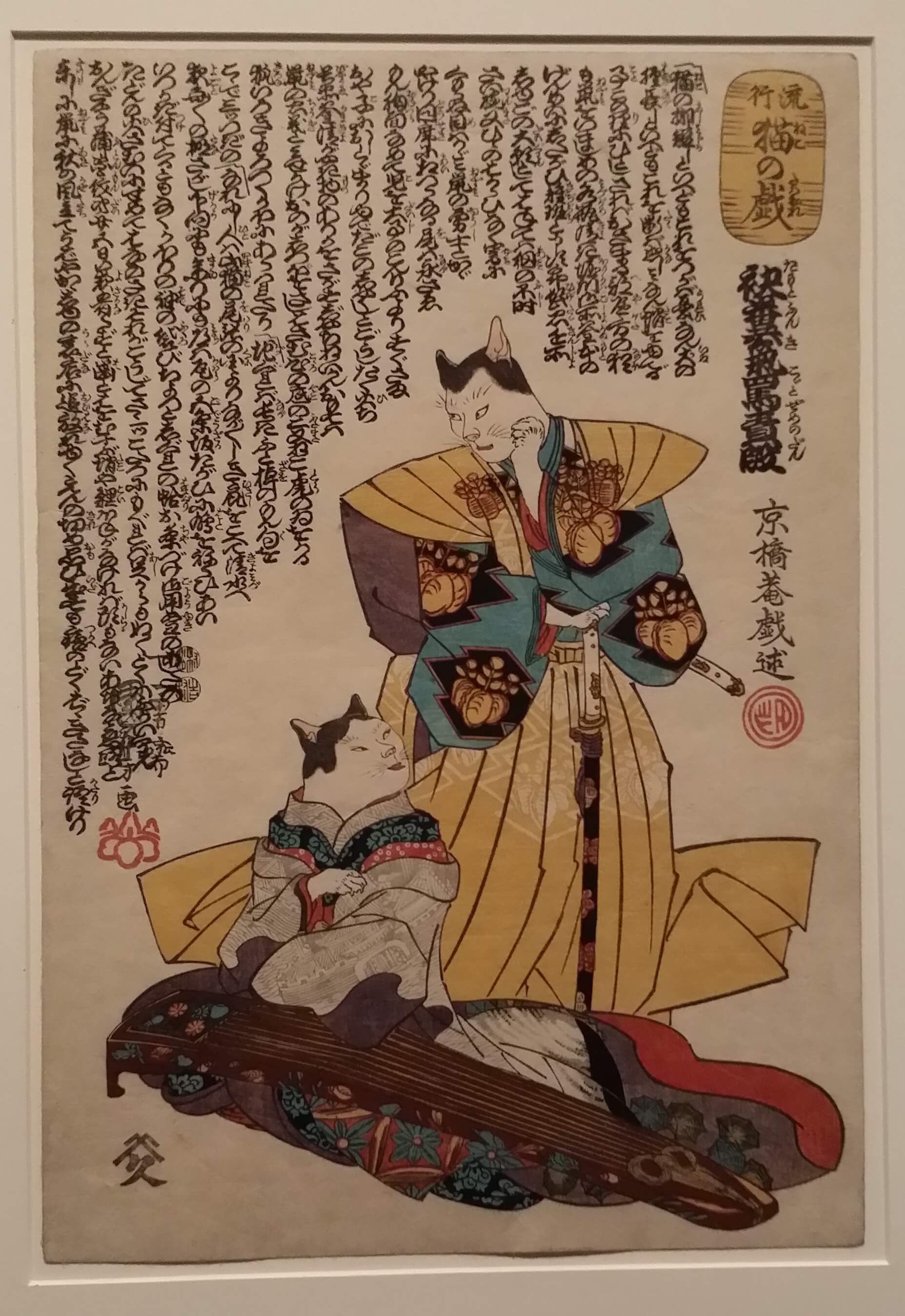

The Scene of Torture by Scolding from the play The Stinky Sleeve from the series Fashionable Cat Frolics. Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

The series Fashionable Cat Frolics is based on Kabuki play parodies written by Santō Kyōzan and illustrated by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Like Kuniyoshi, Kyōzan was also a lover of cats, himself having kept three as pets. Parodies like this were popular during the mid-nineteenth century due to censorship that came with the feudal reforms enacted by the shogunate. Identifiable likenesses of actors and courtesans fell under that, so portraying them as cats was a way of getting around that. This print is a scene from the play The Stinky Sleeve, a tale about the Genji clan and Heike clan who fought one another during the Heian period. Here, a Genji clansman questions his lover Ayako concerning the Heike chieftain. To prove she doesn’t know where he is, Ayako plays the harp, shamisen, and a Chinese string instrument.

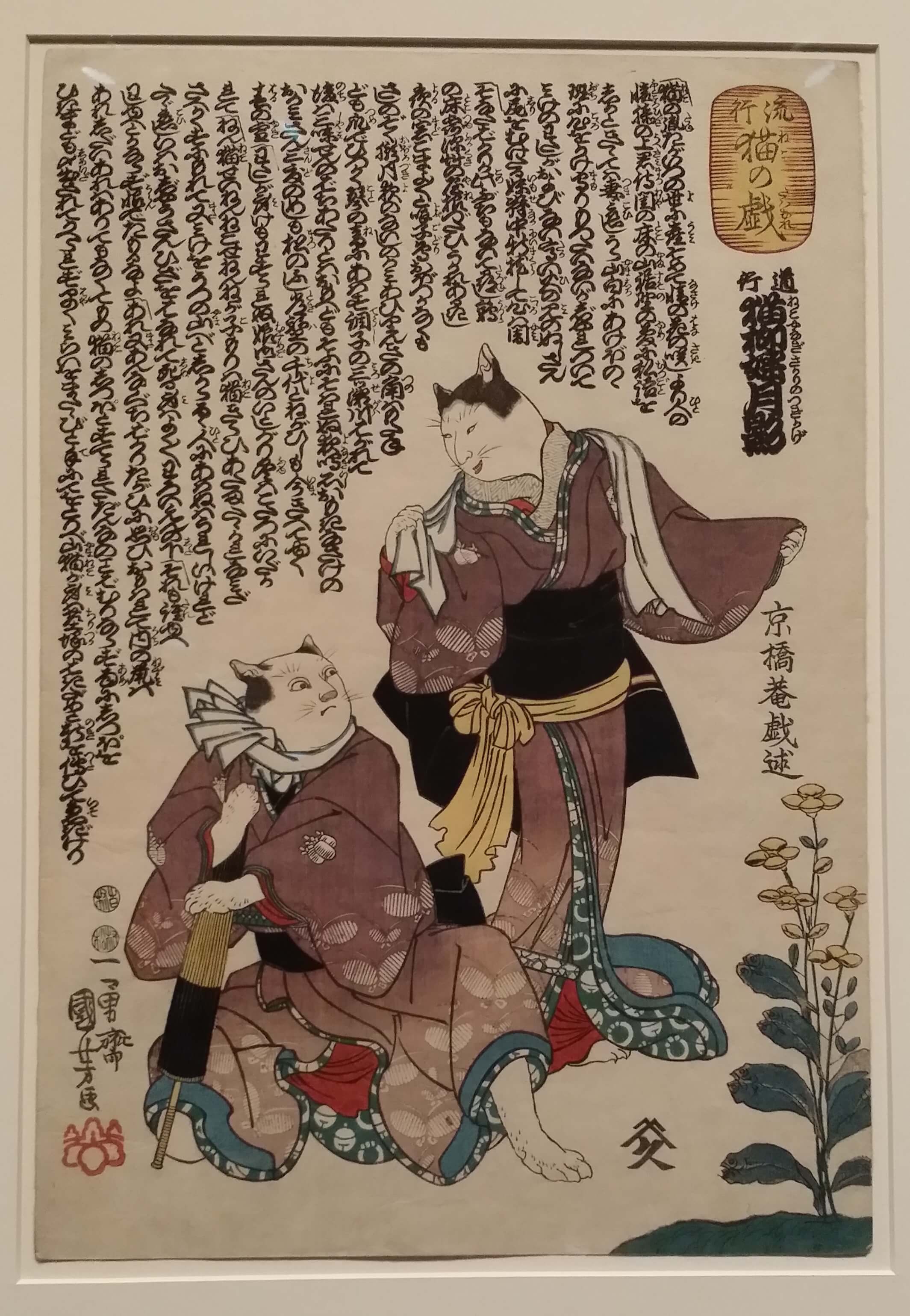

Cats Performing in the Michiyuki Scene in the play Neko yanagi sakari no tsukikage from the series Fashionable Cat Frolics. Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

Another print from the Fashionable Cat Frolics series, this ukiyo-e piece depicts a courtesan named Matsuyama and her lover Kyūbei eloping, a famous scene from the above mentioned play. The print contains a number of items that are typically associated with cats: gold coins and bells on their kimonos, and clam shells and horse mackerel fillets in place of willow flowers and their leaves.

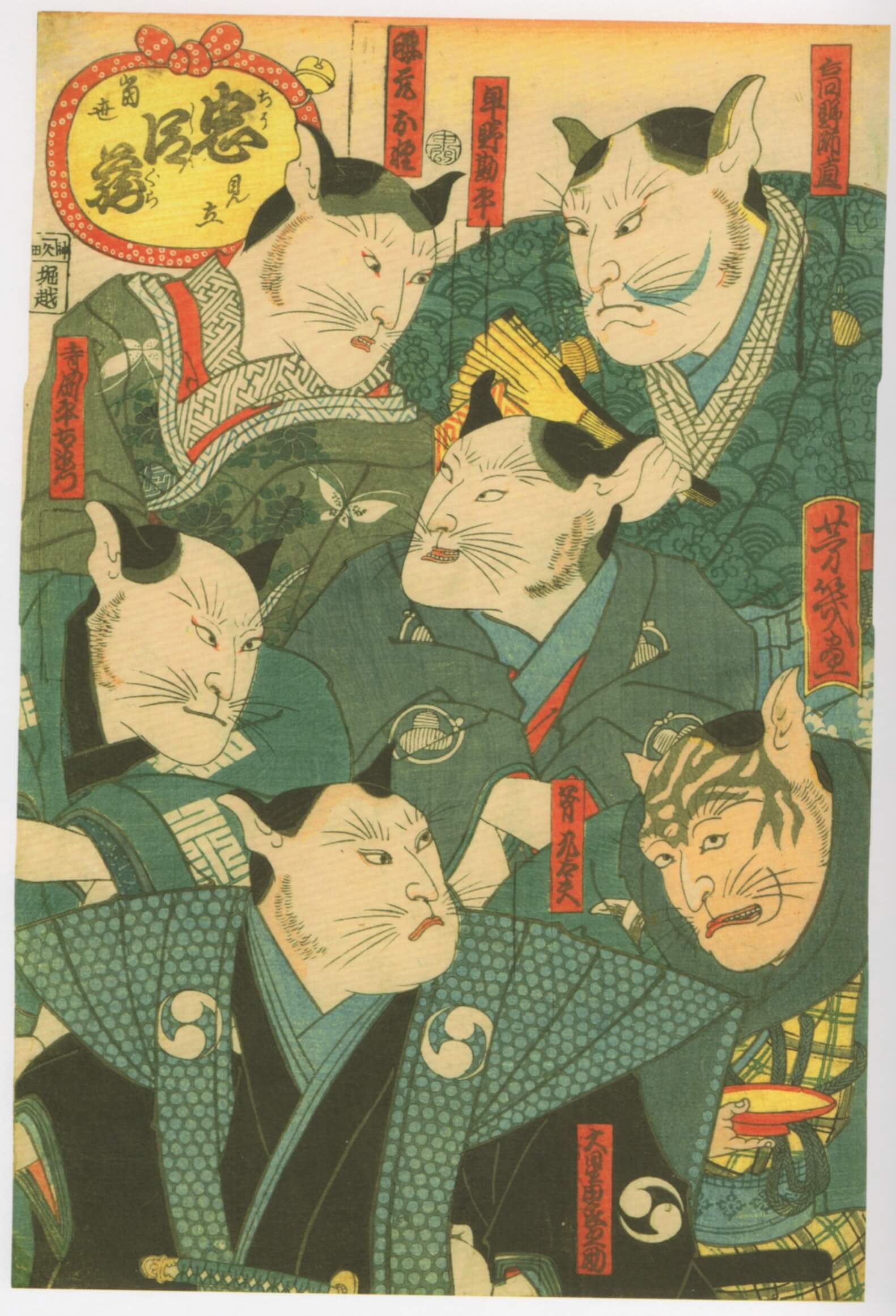

Act 7 from the series Modern Parody of Chūshingura. Print by Utagawa Yoshiiku.

Act 7 shows seven famous Kabuki actors from the Edo period portraying characters from a popular play adaptation of Chūshingura, famously known in the West as Forty-Seven Ronin. This print is a great example of how artists would work around the limitations of censorship: the actors are wearing stage make-up to give them the look of cats, but enough of their own features are left in place so that they would be rather easy to identify for Kabuki fans.

Act 7 shows seven famous Kabuki actors from the Edo period portraying characters from a popular play adaptation of Chūshingura, famously known in the West as Forty-Seven Ronin. This print is a great example of how artists would work around the limitations of censorship: the actors are wearing stage make-up to give them the look of cats, but enough of their own features are left in place so that they would be rather easy to identify for Kabuki fans.

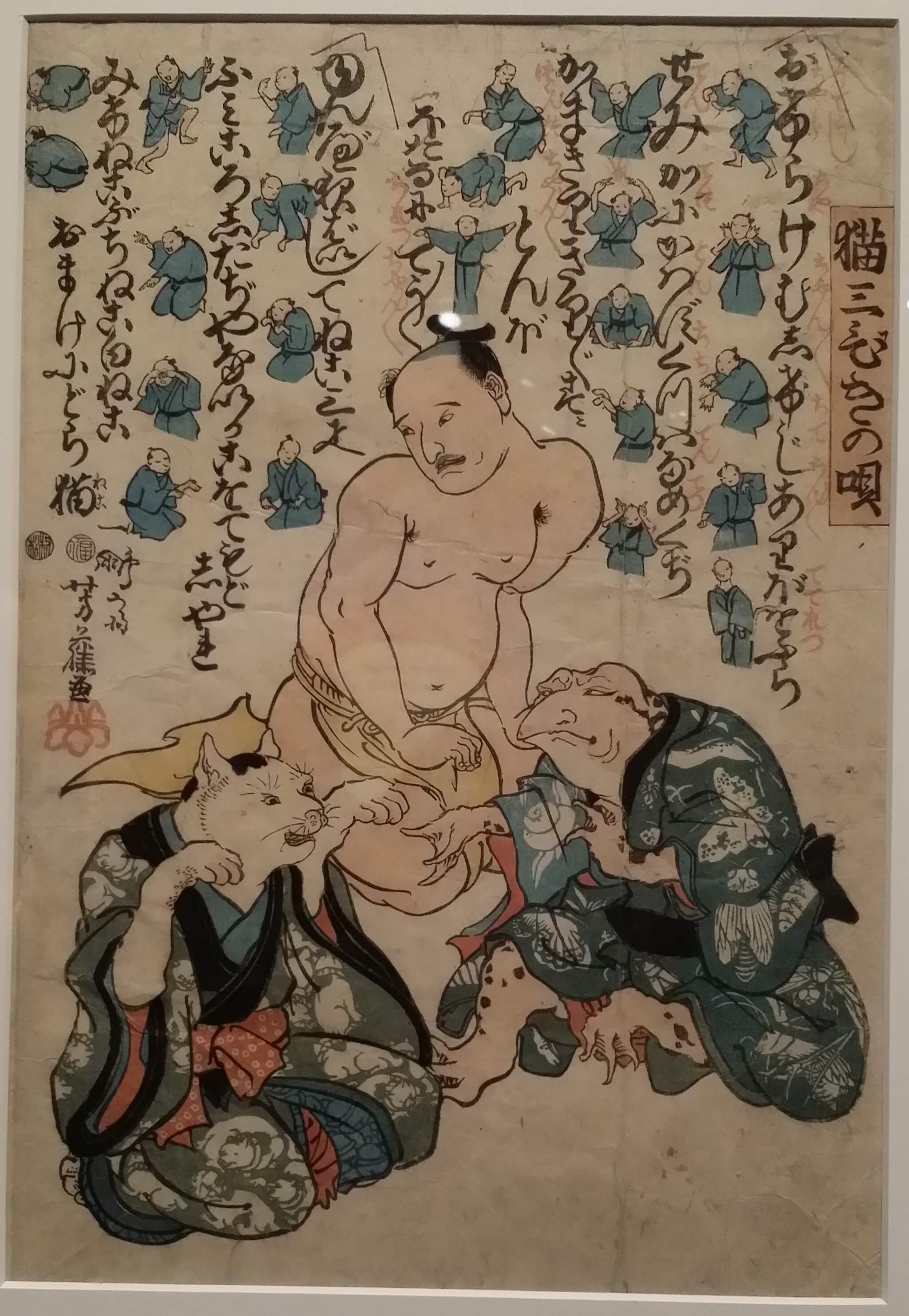

Songs of the Three Cats. Print by Utagawa Yoshiiku.

This print showcases a popular drinking game during the Edo period called Kitsune-ken (“fox fist”). The original game consists of three characters: a fox, a hunter, and the head of a village. The fox wins against the head of a village, the head of a village wins against the hunter, and the hunter wins against the fox. Here, the cat takes on the role of the fox against a frog and a man sneaking into his lover’s bedroom. The background of the print features instructions for a song and a dance, meaning a game like this may have been popular at drinking parties.

Cats versus People

The third segment of the exhibit featured prints depicting cats as antagonists to humans. The arrival of cats in Japan is connected with the arrival of Buddhism: it’s possible that they were on board ships carrying Buddhist scriptures that were sailing from China to Japan. Despite the notion that they were brought along as guardians of these scriptures, cats were also known for mischievous deeds like stealing food or destroying things. This aspect, along with their mysterious nature, has been explored repeatedly in folk tales, leading to the creation of the bake neko, or “cat monster.” Nekomata, one such cat monster, appears in the writings of the Kamakura period (1185-1333), during which numerous famines and natural disasters occurred and cats had to fend for themselves.

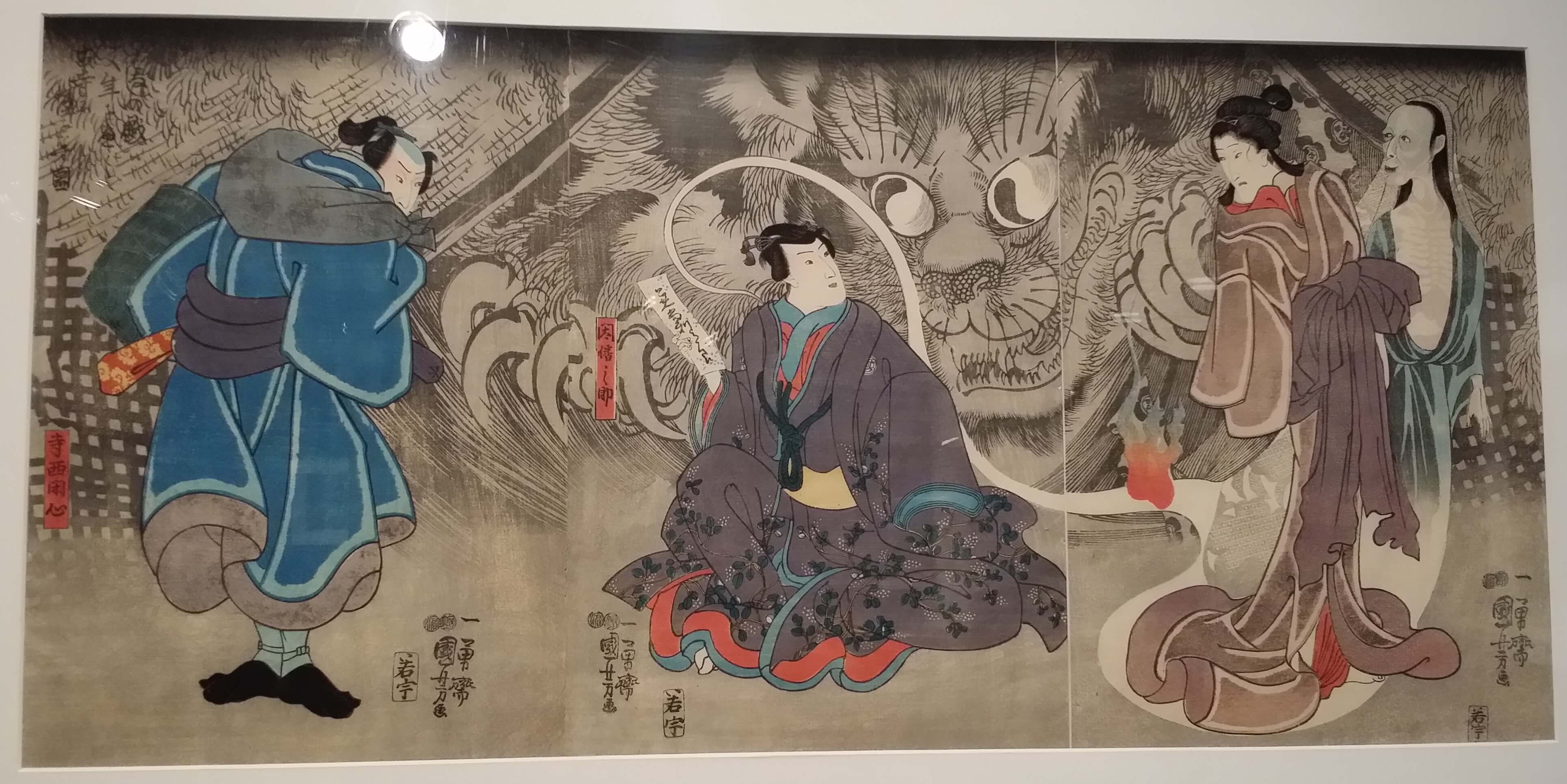

The Old Story of the Okazaki Cat Demon in an Old Temple: Inabanosuke and Teranishi Kanshin. Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

The folk tale of Nekomata is one of the most famous stories involving cats, and stories depicting the creature were rather popular during the Edo period. The basic lore concerning Nekomata is that of an old cat that turns into the larger feline with a tail that’s split at the end. This print is from a later version of the 1827 Kabuki play about Nekomata, who was portrayed by Onoe Baiju (previously called Onoe Kikugorō III). The story involves a stone that holds the spirit of a murdered woman seeking revenge. Here, two travelers encounter a ghost from the netherworld due to Nekomata’s magic.

Onoe Kikugorō III as the Cat Witch of Okabe, Representing Okazaki on the Tōkaidō Road. Print by Gountei Sadahide.

This print depicts a Kabuki adaptation of the tale of the cat-shaped stone at Okazaki Station (in present-day Shizuoka Prefecture) along the Tōkaidō Road. The 1827 play starred Onoe Kikugorō III (later named Onoe Baiju, as stated above) as Nekomata, who emerges from an old cat that has a split tail. Nekomata appears as an old innkeeper at first, but when night falls and she licks oil from a lantern, her true form is shown via a cat shadow on the lantern’s paper. Here, she is slowly turning into her true form while a pair of cats dance on their hind legs.

This print depicts a Kabuki adaptation of the tale of the cat-shaped stone at Okazaki Station (in present-day Shizuoka Prefecture) along the Tōkaidō Road. The 1827 play starred Onoe Kikugorō III (later named Onoe Baiju, as stated above) as Nekomata, who emerges from an old cat that has a split tail. Nekomata appears as an old innkeeper at first, but when night falls and she licks oil from a lantern, her true form is shown via a cat shadow on the lantern’s paper. Here, she is slowly turning into her true form while a pair of cats dance on their hind legs.

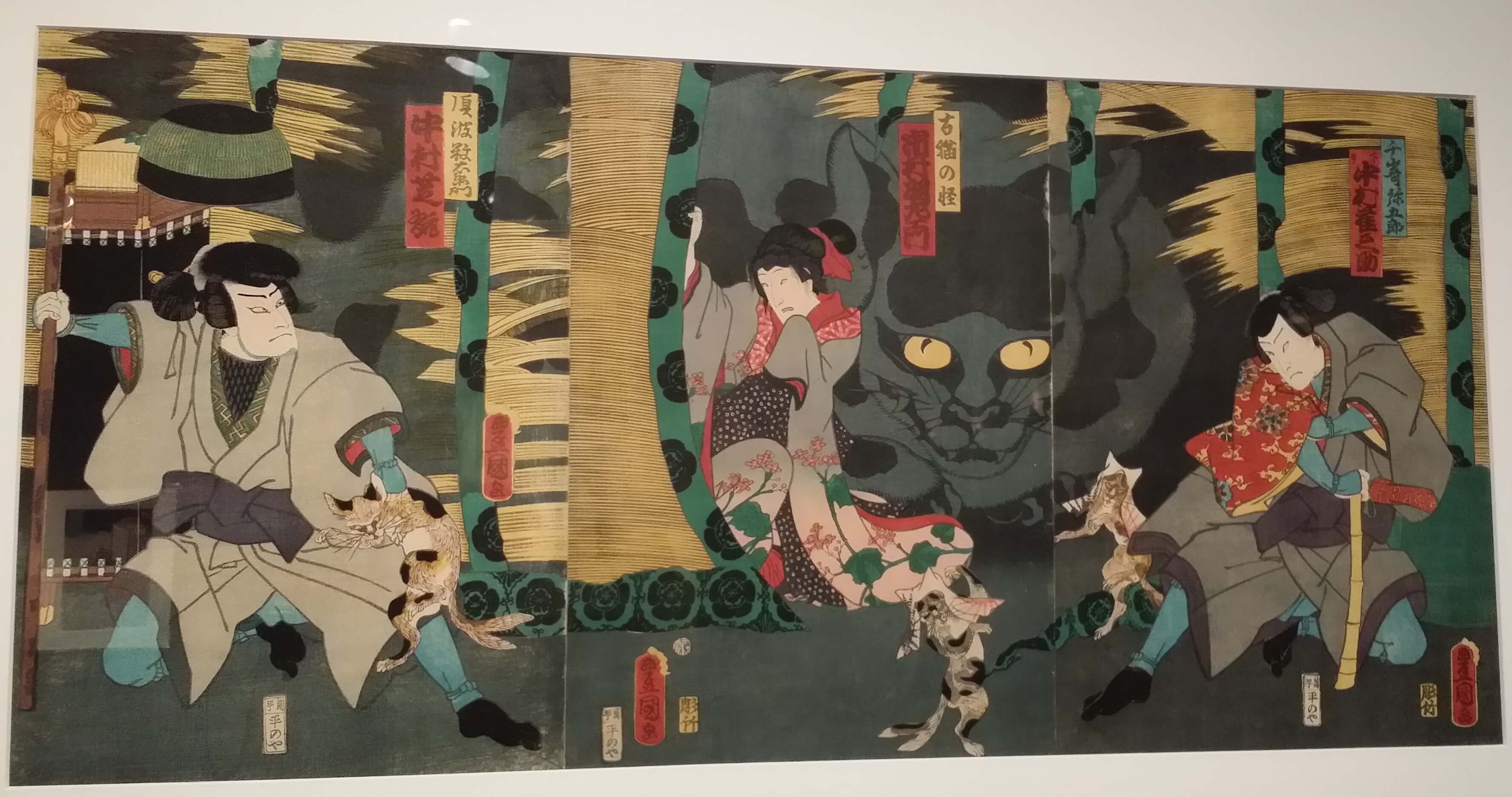

Actors Nakamura Jakunosuke as Senzaki Yagorō, Ichimura Uzaemon XII as the Monster of Old Cat, Nakamura Shikan IV as Suwa Kazuemon. Print by Utagawa Kunisada.

Another print featuring Nekomata, Monster of Old Cat has the monster cat transform into a beautiful dance instructor rather than an old woman. The reason for this is because the actor in the role, Ichimura Uzaemon XII, was nineteen years-old and was considered to be a “shining beauty.” Kunisada depicts Nekomata as a looming presence on the stage’s backdrop, with cats dancing in the foreground on their hind legs in a similar fashion as the previous ukiyo-e print.

Cats Transformed

The fourth portion of the exhibit focused on prints that depict cats as models for other creatures and prints that strived to depict cats realistically. Because larger cats weren’t native to Japan, like tigers or lions, Edo artists would use cats as models for these felines. One clue is to look at the animal’s eyes: while domestic cats have slit pupils, tigers, for example, do not, meaning a cat would have been the model for the work.

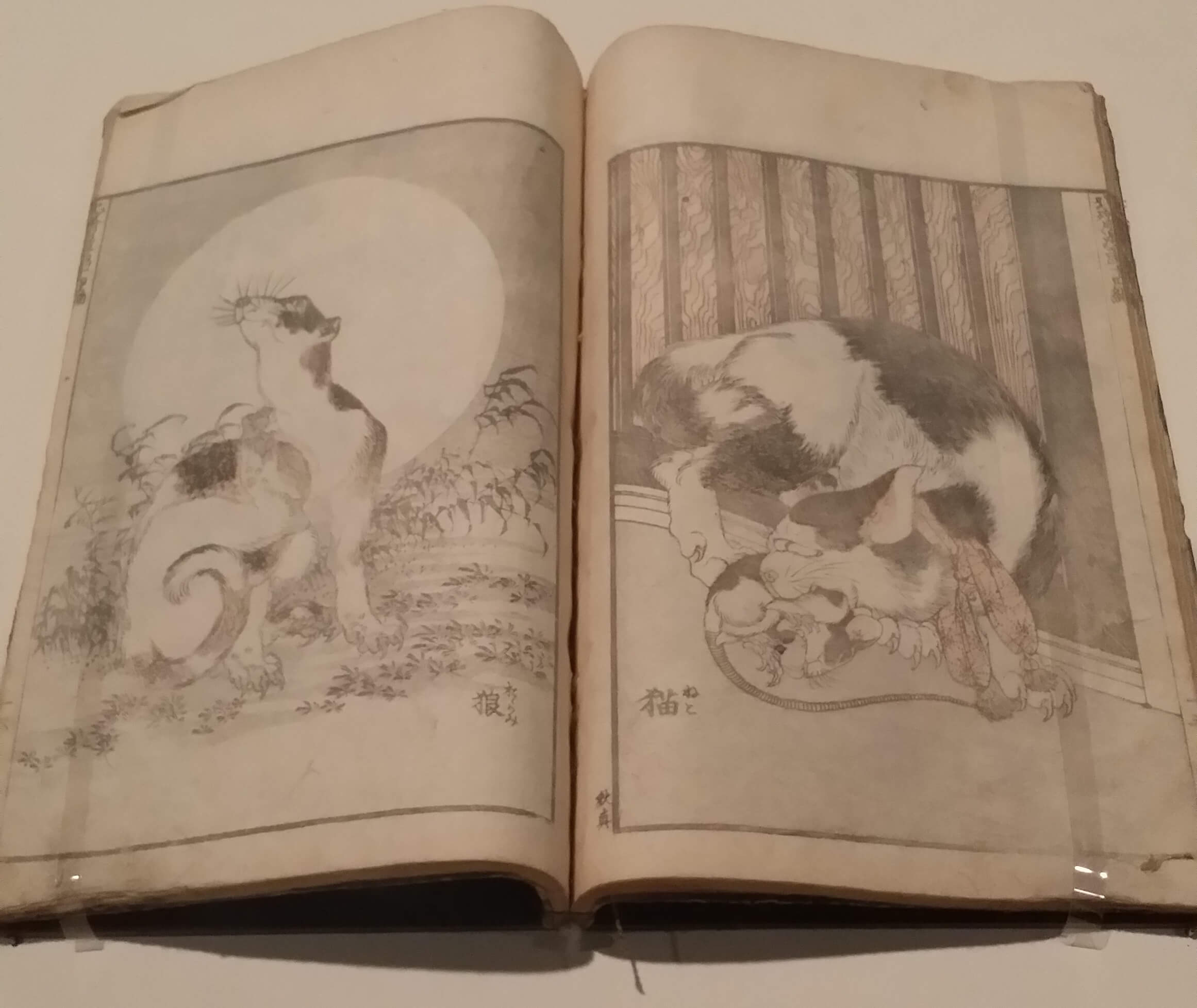

Hokusai Manga. Work by Katsushika Hokusai.

With this book of illustrations, Katsushika Hokusai drew cats more realistically, such as fierce hunters of smaller creatures. This goes against other portrayals of cats shown so far, such as that of a furry companion or a monstrous creature. The drawings also go along with one of their major functions in the highly-urban Edo: that of helping to control the rodent population. The cat’s Asanoha-mon (“hemp leaf pattern”) neck ribbon is a common feature of domesticated cats in ukiyo-e.

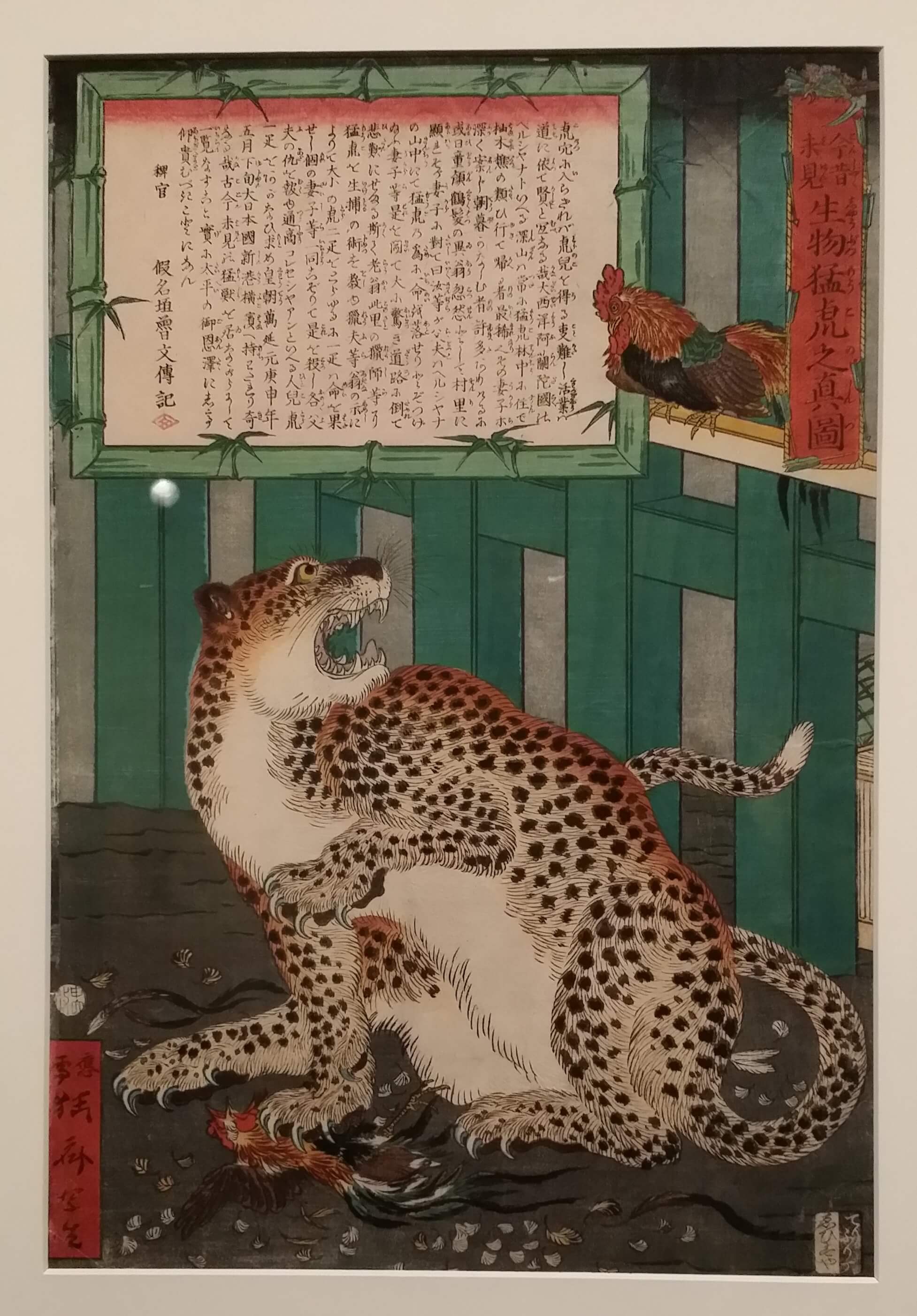

A True Picture of the Fierce Live Tiger Never Seen from the Past to the Present. Print by Kawanabe Kyōsai.

The artist of this print, Kawanabe Kyōsai, attended a misemono-goya (“curio show”) in eastern Edo where he saw this live “tiger.” The text on the print, written by Kangaki Robun, explains that the print is of a “baby tiger” brought over by a Dutch merchant ship. Due to the lack of large cats in Japan, species were often confused with one another. For example, images of tigers would be thought of as male tigers, while leopards, like the one here, would be taken as female tigers.

The artist of this print, Kawanabe Kyōsai, attended a misemono-goya (“curio show”) in eastern Edo where he saw this live “tiger.” The text on the print, written by Kangaki Robun, explains that the print is of a “baby tiger” brought over by a Dutch merchant ship. Due to the lack of large cats in Japan, species were often confused with one another. For example, images of tigers would be thought of as male tigers, while leopards, like the one here, would be taken as female tigers.

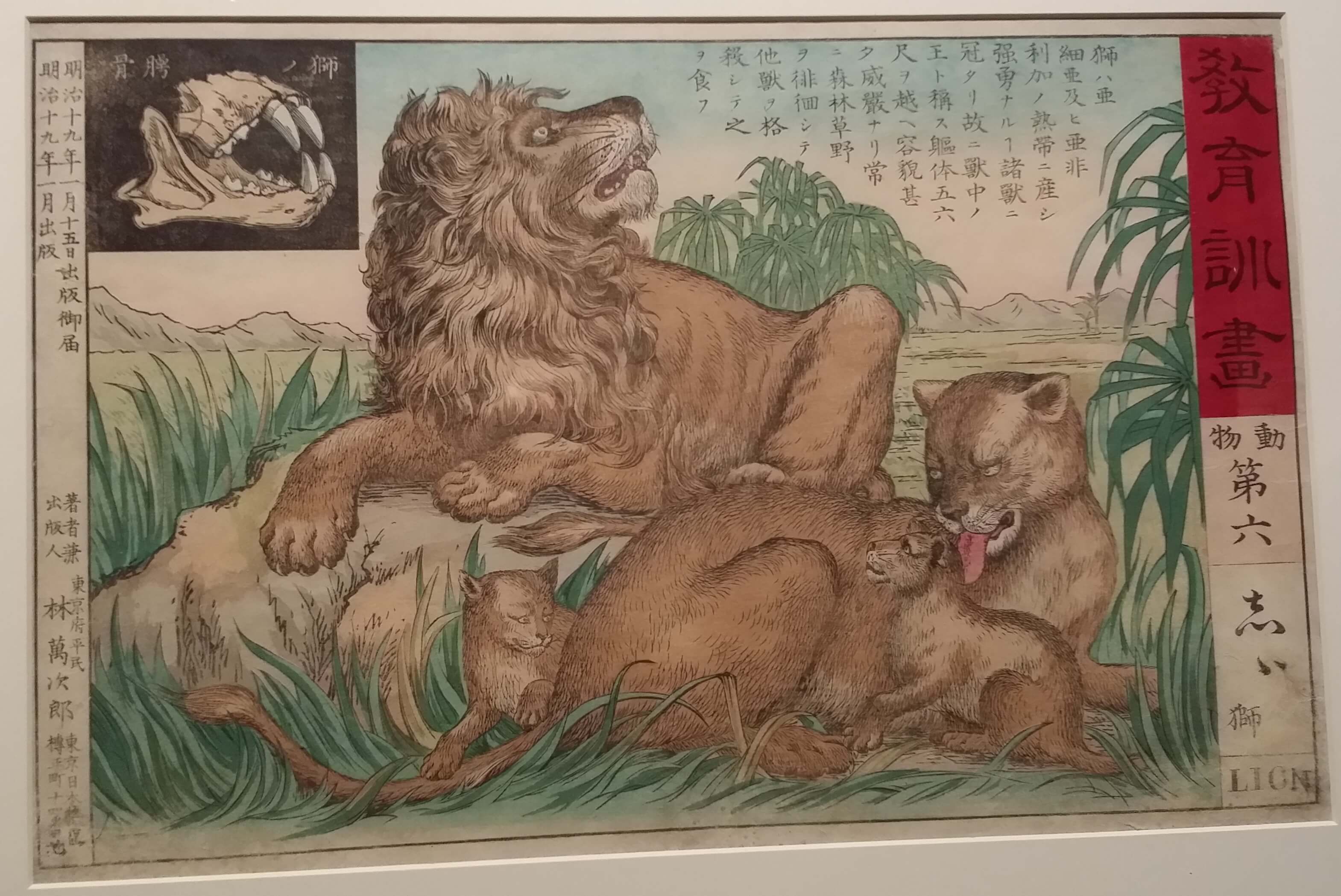

Education Print no. 6: Lions. Print by Unknown Artist.

As opposed to the artist endeavors of the pieces shown thus far, this ukiyo-e print was created to educate others about the lion. The image of the lion family is likely based on images found in natural history books that had been imported to Japan from Europe since the early Edo period. Japanese artists and scholars would frequently copy the images from these books. The print here informs viewers that the lion is “the king of beasts” and can be found in Africa.

Cats and Play

The final segment of the exhibit consisted of omocha-e, or “toy pictures,” featuring cats. There were a few functions for this these prints: while being entertaining for children to look at, they also helped teach children how to read, write, and count, as well as instructing viewers on the moral lessons and proper social conduct stemming from Confucian principles, which the Edo government followed. Omocha-e were mass-produced, in heavy use, and often are credited as being produced by an anonymous artist. These prints follow the giga tradition, so many of them depict cats doing human activities.

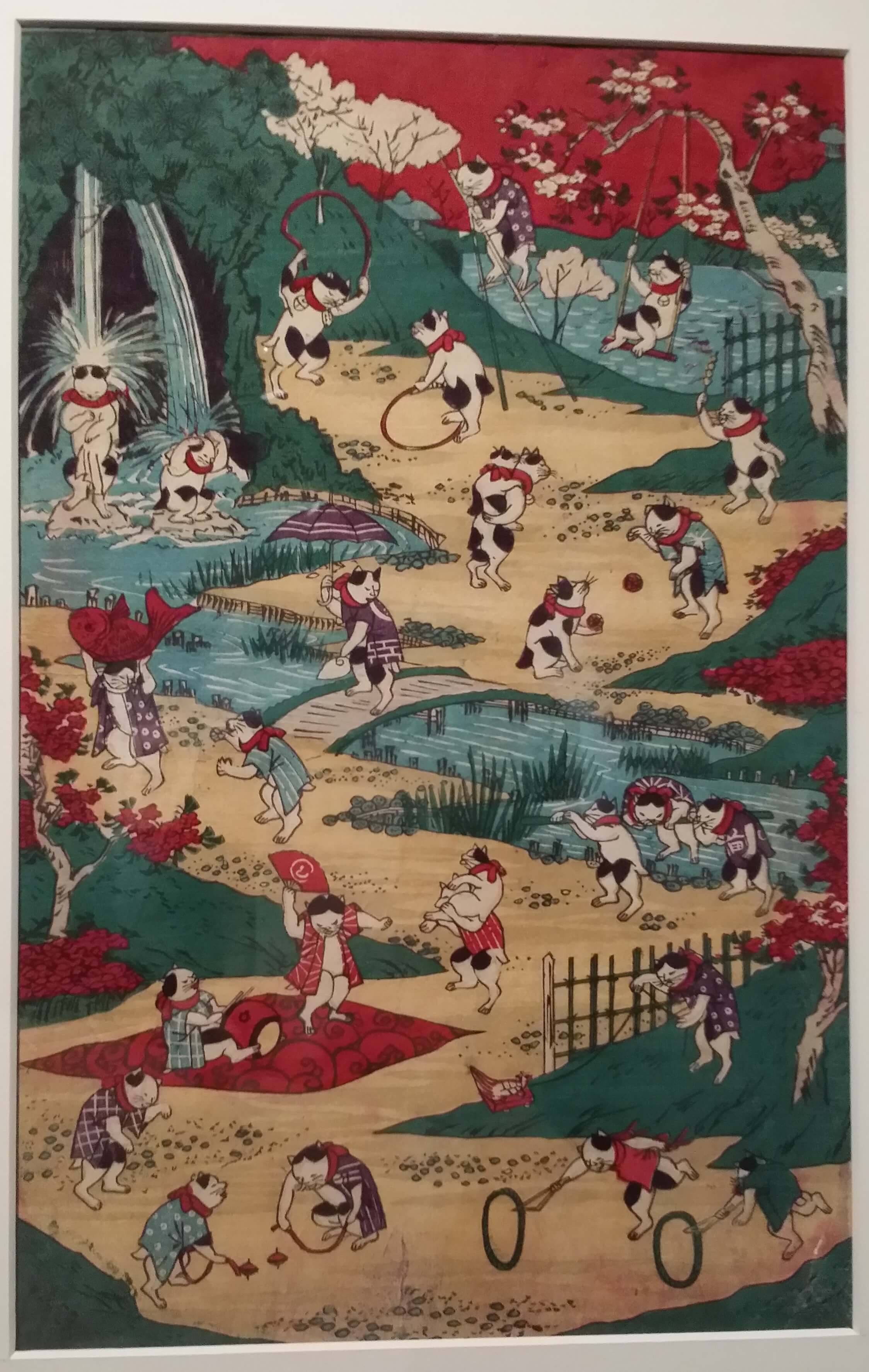

Newly Published Cat’s Games. Print by Utagawa Kunitoshi.

This omocha-e shows cats partaking in various children’s games. One cat can be seen crossing a bridge while holding an umbrella. This Western-style umbrella references the excitement of the Meiji period due to the new technologies and inventions that were imported into the country. Omocha-e during this period were frequently made to educate children about various Western objects and customs.

This omocha-e shows cats partaking in various children’s games. One cat can be seen crossing a bridge while holding an umbrella. This Western-style umbrella references the excitement of the Meiji period due to the new technologies and inventions that were imported into the country. Omocha-e during this period were frequently made to educate children about various Western objects and customs.

Catfish. Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

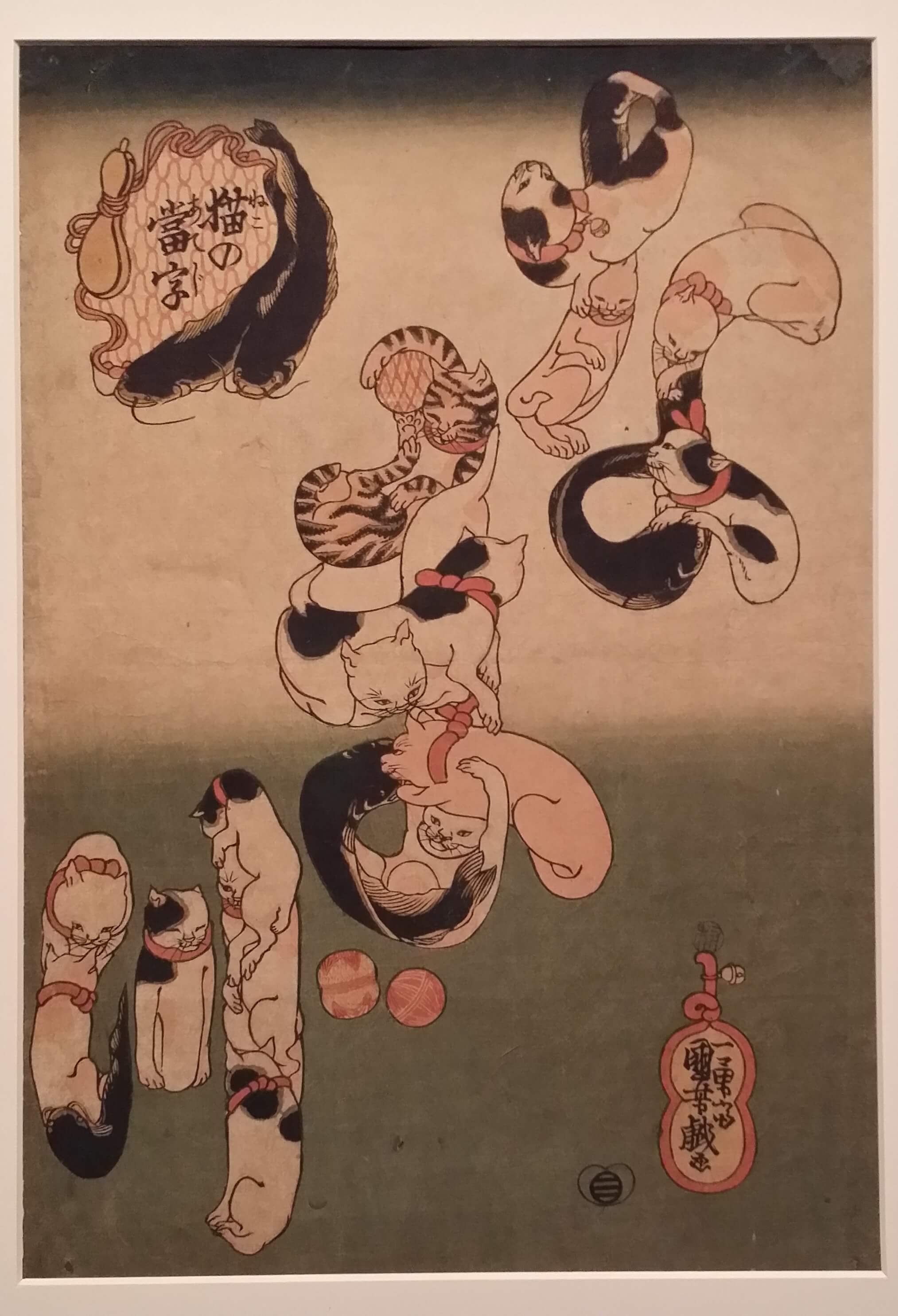

Made by known cat-lover Utagawa Kuniyoshi, this playful design features cats spelling out the hiragana characters of “na,” “ma,” and “zu,” starting from the upper-right corner and going down to the lower-left corner of the print. In Japanese, namazu happens to be the word for “catfish,” allowing the pun to easily retain its meaning in the English translation.

Made by known cat-lover Utagawa Kuniyoshi, this playful design features cats spelling out the hiragana characters of “na,” “ma,” and “zu,” starting from the upper-right corner and going down to the lower-left corner of the print. In Japanese, namazu happens to be the word for “catfish,” allowing the pun to easily retain its meaning in the English translation.

Newly Published Scenes of Good and Evil Cats. Print by Unknown Artist.

Like the first omocha-e print in this section, the purpose of this print is to educate children. One half of the picture shows good deeds being done and happy occasions being celebrated, like visiting a shrine or celebrating the birth of a child. The other half shows acts considered immoral, such as fighting with a parent or begging on the street.

Like the first omocha-e print in this section, the purpose of this print is to educate children. One half of the picture shows good deeds being done and happy occasions being celebrated, like visiting a shrine or celebrating the birth of a child. The other half shows acts considered immoral, such as fighting with a parent or begging on the street.

I hope you enjoyed this look at various Japanese ukiyo-e prints featuring cats! Thank you to the Japan Society for putting together a wonderful exhibit. Were there any that you’ve seen before? Which ones were your favorite or the most interesting? Let us know in the comment section below!

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page