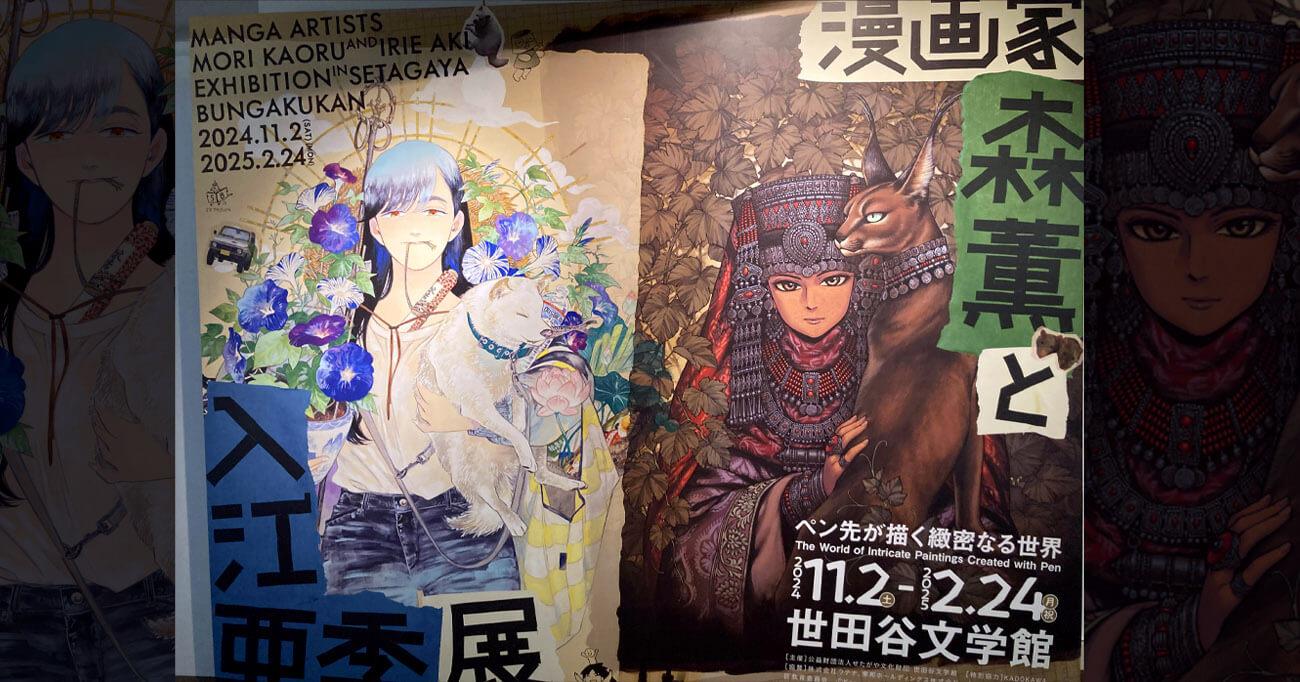

Kaoru Mori is the beloved manga artist behind historical fiction classics A Bride’s Story and Emma. Aki Irie is an equally talented creator responsible for such works as Ran and the Grey World and Go With the Clouds North By Northwest. While I adore both, I never thought to connect the two. Yet Mori and Irie both started out in the doujinshi market, became professional manga artists around the same time, and were even serialized in the same magazines (Comic Beam, Harta, and Aokishi). “Intricate Worlds Drawn in Pen,” an exhibit hosted by Setagaya Literary Museum in Tokyo, displays Mori and Irie’s artwork side by side. The exhibit asks: what else do these two artists have in common? Where do they diverge?

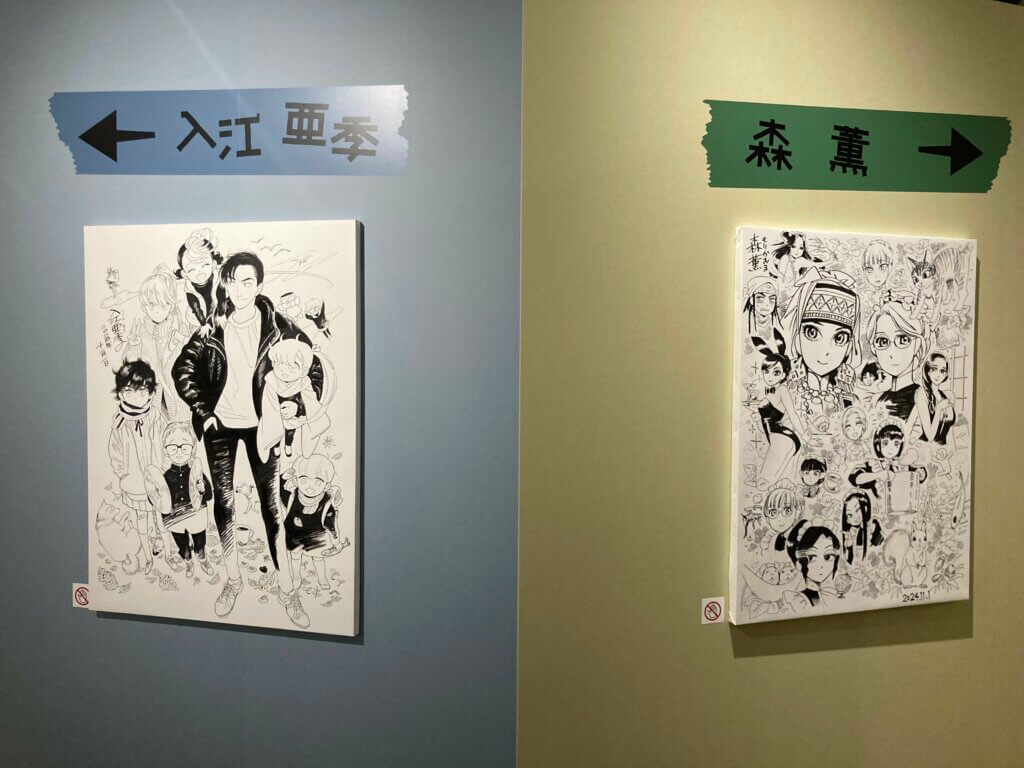

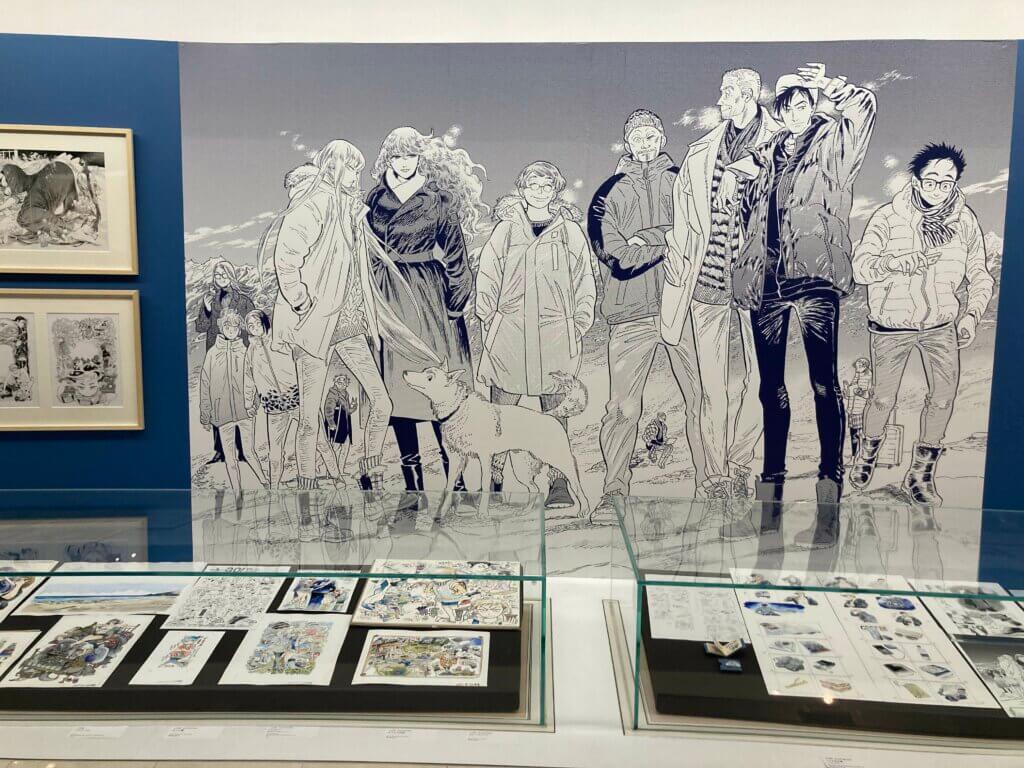

The opening fork in the road splits into separate chambers commemorating Mori and Irie. Manga pages and illustrations by each author dot the walls of their respective sections. Others rest beneath rectangular glass cases below wall-sized images capturing key scenes. To stand surrounded by Mori or Irie’s art is to see their exhibition partner peeking out from behind corners and the sides of pillars.

Changing scenery

The appeal of Mori and Irie’s artwork stands out that much more when put into conversation. Mori’s drawings, particularly those associated with her ongoing series A Bride’s Story, are carefully observed and yet always readable. A scene where a young woman named Amir pursues a rabbit by horseback perfectly captures the subjects while omitting all other details. Meanwhile, Irie’s line has a certain ebullience, whether she’s drawing young girls that transform into adult women via magical sneakers (Ran and the Grey World) or men wandering across Iceland (Go With the Clouds North-by-Northwest.)

Mori and Irie converse not just through their art but via written blurbs displayed throughout the exhibit. Irie says of her work that she pursues “the changing scenery as you travel to somewhere far, far away, stepping onto the soil of a new place for the first time…” As she experiences new things, she conveys these discoveries through her characters, who grow in turn. The reader’s world expands as well. Meanwhile, Mori writes that “I prefer to calmly fix my gaze on the established, unchanging past rather than focus on the constantly shifting present.” She comes up with ideas via detailed research rather than personal travel experience.

Freely and with no constraints

The two artists are also very aware of each other’s tics. Mori describes Irie’s comics as “rhythmic,” noting that she typically uses many more panels than is common for manga. (While most seinen manga per Mori “have an average of seven panels per page,” Irie’s pages can exceed twelve or even thirteen panels.) Irie on the other hand admires Mori’s close connection with her fans, writing that they “are lucky to be able to enjoy the works of a creator who is so sensitive and attentive to their needs.”

The exhibit makes space for specific points of commonality between Mori and Irie. One is their past experience making doujinshi. (Copies of these early works were on display both on walls and behind glass cases.) While the two of them began their careers this field, they took different lessons away from the experience. Irie was most impressed by the boundless sense of possibility represented by doujin. “I too wanted to use the medium to express myself,” she says, “freely and with no constraints.”

Mori instead was thankful that drawing doujinshi let her speak with her readership one-on-one at conventions. “Some creators who start their serializations by submitting or pitching their works directly,” she says, “without ever having met their readers, feel uneasy because they can’t picture who’s reading their manga.” Mori felt lucky to work alongside her readers rather than relying on her host magazine’s inbuilt audience.

Integrity

The idea of satisfying fans as an artistic pursuit in itself requires some explanation. I’ve seen some pushback in artist circles from folks who insist that making art for yourself, rather than for others, is the most important thing. Can you really trust your readership? Mori did; she loved drawing people wearing uniforms, and became a professional artist with the support of devoted readers from her doujinshi days.

Irie is even more outspoken when it comes to the question of making art for your fans. “Some may feel that trying to please readers is an act of pandering that compromises the work’s integrity,” she says. “But why view it in such a negative light?” Irie does not reject art as personal expression out of hand. In fact, she insists that artists must imagine what they want to create rather than blindly follow what other people expect from them.

Animals close by

Animals play prominent roles in Mori and Irie’s works. Mori’s A Bride’s Story features many animals (rabbits, horses, wolves) common to Central Asia during the 19th century. Mori currently has eleven pets including cats, fancy rats, hermit crabs and snails. “While I want to raise many different kinds of pets,” she says, “I have conflicting feelings about possessing living creatures purely for my own enjoyment. Still, I can’t give up on my desire to have animals close by.” Her work treats animals and nature with a similar respect, depicting them as they are rather than portraying them as purely cute or human-like.

Meanwhile, Irie has a fierce love of dogs. She describes her pet shiba inu as being difficult in ways that owners of this breed will recognize. This dog “acts a bit thuggish” around other pets, “doesn’t meet me at the door” and tries to shove her out of bed every morning for walks. Yet Irie believes that “having a dog is like a happy dream, even when I think about the inevitable sadness of parting.” A pet’s stubborn nature is just another charm point for her.

![Nook of books featuring various translated editions of A Bride’s Story’s [italics] first volume, as well as recommended titles from Aki Irie. At the end is a wall hanging depicting a young woman with short black hair wearing a maid costume as seen through a door that she is opening.](https://yattatachi.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IMG_4780-1024x768.jpeg)

Yosoi

“Intricate Worlds Drawn in Pen” hosted a number of physical objects besides manga art. Two desks featuring drawing materials modeled Mori and Irie’s respective work spaces. There was also a selection of what the exhibit called “yosoi,” meaning clothing and decorations. Mori’s work is especially famous for the way in which she depicts clothing and fabric. But Irie also utilizes clothing in her comics as a means of fleshing out settings: for instance, the cold of Iceland. Carpets, fur coats and sweaters were all on display in the museum. There was even a tiny model of a Zuzuki Jimmy JA11, a type of car that appears in Go With the Clouds North by Northwest (and that Irie herself bought used.)

My personal favorite section was a nook in the back featuring Mori and Irie’s personal favorite books. Some of these were presumably reference material, such as Mori’s recommendation Black and White Images: Fifth Special Collection. Others were fictional novels or comics that inspired these two artists. Irie for instance spotlighted Mitsuru Adachi’s Nijiiro Togashi as well as Moto Hagio’s Gin no Sankaku. While I’m familiar with Adachi and Hagio, I had never heard of either of these works. It reminded me of just how much my own knowledge of manga history is shaped by a handful of titles published abroad.

I can feel the pen in my hand

The title “Intricate Worlds Drawn in Pen” suggests the importance of physical materials. Aside from the matter of generative AI and large language models, many artists today produce their comics digitally via drawing tablets or programs like Clip Studio Paint. These techniques allow for different strengths and weaknesses than can be observed in comics drawn with pen and ink. This exhibit by contrast reaffirms the appeal of ink. “Even with the most delicate of lines,” reads a blurb at the start, “you can feel the strength in the strokes of their pens.”

“I can’t fully trust the digital world,” Irie says, “because–to put it simply–it doesn’t exist. When I draw the first line of the day, I can feel the pen in my hand and the texture of the paper.” Temperature, humidity, the quality of the ink and even her own feelings affect her drawings. To her this is a strength rather than a weakness. In fact, it was picking up a dip pen in high school that made her want to be an artist. She still has trouble using them after twenty years. Yet she believes that “I have never been able to imagine drawing with anything else.”

Reckless abandon

Mori is less explicit in her remarks about the physical qualities of her comics. But she does speak honestly about what she sees to be the strengths and weaknesses of her works. Mori began her first series Emma with what she calls “reckless abandon,” and by her own admission learned a lot about how to create manga during its serialization. A Bride’s Story is the result of this newly capable and ambitious artist building on earlier lessons. “It’s only after finishing a manga,” she says, “that your skills jump to the next level.”

Mori is also credited for a “How to Draw Manga” section within the exhibit that breaks down the process into seven steps, beginning with sketches and ending with the application of screentone. The same work of art is iterated upon piece by piece to come together into a finished product. While it’s tempting to assume that great comics magically flow from a manga artist’s pen, this exhibit instead makes the case that manga creation is always a material process of assembly regardless of individual skill.

A greenhouse for rice seedlings

The exhibit ends with remarks addressed to “manga artists of the future.” Mori recommends the world of doujinshi as a “greenhouse for rice seedlings,” an environment for young manga artists to improve their skills and find readers. The advantage of doujinshi, she says, is that “only the people who like your manga will buy them…those who don’t aren’t going to say anything negative to you.” In other words, it’s a place where artists can further polish aspects of their work that readers respond to without being caught up in what those readers dislike.

Irie meanwhile recommends that growing artists think carefully about what they are making and why. “Some people say that they don’t understand their own art,” she says. “But how can you choose the correct knife if you don’t know what you’re going to cut?” Despite Irie’s tendencies towards improvisation, she always considers what tools that she is using and in which condition before starting a project. These small details are all important to create comics that achieve an intended effect.

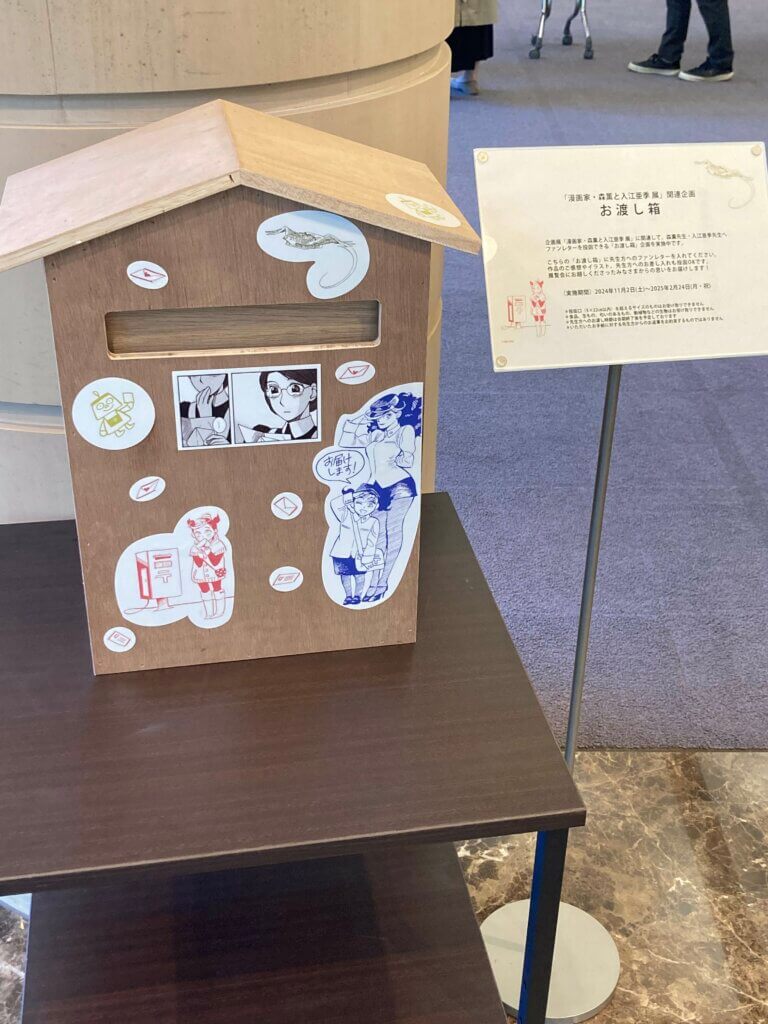

The power of manga

Outside the exhibit, two paper notebooks overflowed with fan tributes to Mori and Irie. It’s no surprise that artists raised in the world of doujinshi inspired such a loyal readership. Speaking personally, I was overjoyed to see an exhibit take comics so seriously; not just as a literary medium, but as a physical process of creation. You could not stand in that space without being overcome by the power of manga.

Gallery

Article editor: Kelly Stewart

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page