One of Kyoto Animation’s most anticipated projects has arrived, and with it a cacophony of the best and worst aspects that come from being such a tight-knit production house. Violet Evergarden boasts cathartic power in every aspect one would expect from a KyoAni production. However, when it touches new ground for the studio, that’s where its weaknesses begin to bleed out.

Like yin-and-yang, the series traverses between episodes that are generally hits to ones that are misses. This is where a pattern is found; each of the best episodes follow a specific singular theme: Violet’s growing realization of life itself. It’s the moments where Violet hits her character beats that carry a transcendent emotion of agony; finding places where beauty can exist in such torment. As a viewer, to feel these expressions as raw as the show’s characters do is the most real treat from the show. Most of these highlights are extended from Haruka Fujita’s involvement with the series.

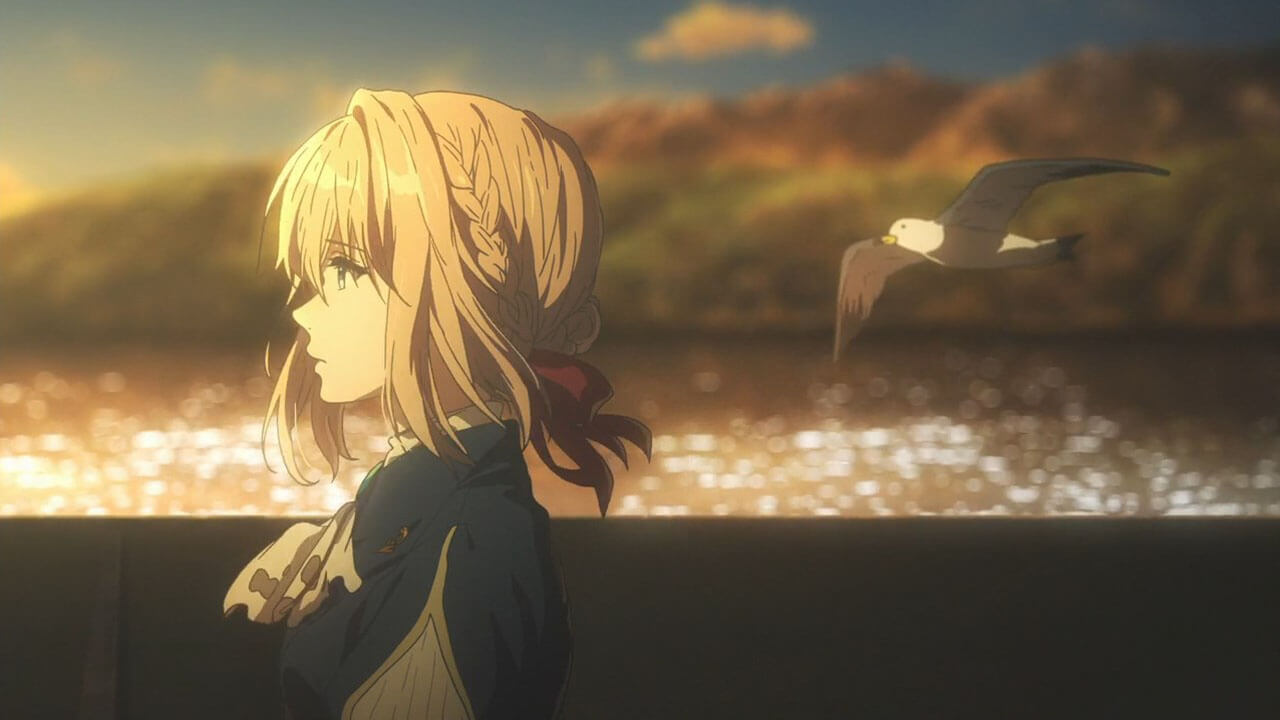

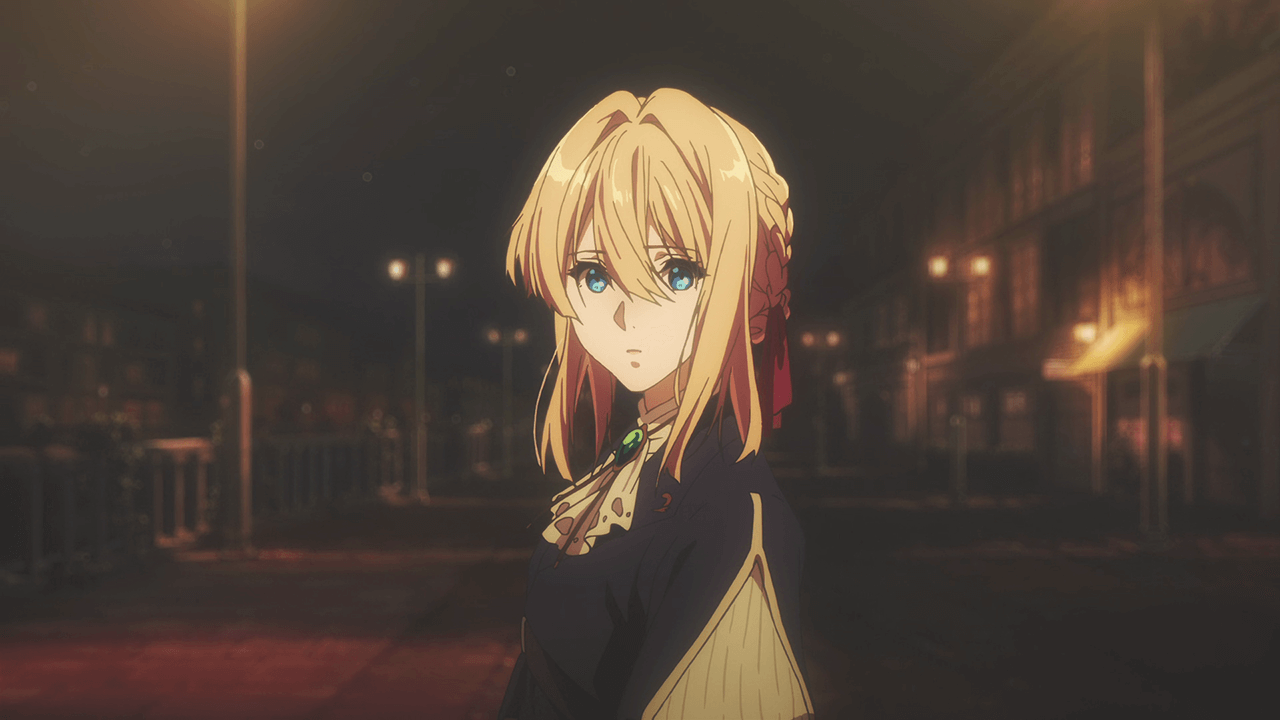

Having gone through years of mentoring, under peers like Naoko Yamada, Fujita is on a clear path to likely surpassing everyone else as KyoAni’s strongest director. Her delicate touch, especially in episodes 5 and 13, illustrates how skillful she is in understanding her characters, what they feel, and how to eclipse those feelings within the audience. There’s a strong sensation that Fujita fell in love with the character of Violet as she was making the show, and she delivers her feelings for Violet in an explosive manner every chance she gets. Near the end of the show, a portrait shot of Violet coming to terms with her reality lingers with immense weight; a visible footprint of Fujita’s directing.

However…

Violet Evergarden is like one of those rare experiences where you feel as if you’re watching two shows in one, both trying to battle each other for the spotlight. The only thing is it’s not exactly the case of watching two shows in one, but rather it’s its own unique experience of watching one good show desperately grasping onto a bad show.

There’s an overarching theme: Violet’s humanization. It’s made evident from the very beginning of the series that the audience can expect this to happen and how it will happen. Generally, we’re satisfyingly given what we’re sold. There are some really sentimental episodic stories told through Violet’s journey. But along with the main dish, there’s an extra side serving of something that was never ordered; another layer to the cake that changes the flavor significantly.

Whenever the show isn’t about the episodic experiences that help Violet understand life, it feels astoundingly unenthused with itself. There’s a subplot that exists throughout the veins of the series that involve a lingering war, other current wars, and the unstable politics within the continent in general. Most of the time, these political subplots don’t coexist very well with the main theme of Violet’s enlightenment.

One of these subplots leads to one of the show’s very awkwardly performed “climaxes”. It’s made relevant to Violet, showing her solid resolve after her transformation, but the genre-switch in execution feels jarring when compared to the strong emotions felt in much less thematically significant moments. When comparing the beginning and end of episode 13, it’s clear that two different people worked on each segment, which brings Taichi Ishidate into discussion.

Not to be glib, but Ishidate is consistently the weakest link among his peers at KyoAni. Putting him to work alongside one of the most promising directors in the studio makes Violet Evergarden a constant ride of yays and nays. The issue with Ishidate is his presentation of character drama, which tends to lack the correct amount of attention and emphasis. His strength shows within his action cuts; they’re always dynamic and tense in movement. However, they tend to lack the emotional weight to sell his intricate shots, but it’s clear why the decision was made to give him a big seat on this anime.

Two Sides of One Coin

Violet Evergarden covers genre elements of both action and drama. Fujita (who has worked on Hibike! Euphonium) tackled many of the dramatic elements. Ishidate (director of Kyoukai no Kanata) tackled most of the more action-y/political elements. While KyoAni has been training a team to produce beautifully animated action sequences, they don’t have any director to consistently tackle storytelling in the genre of action itself. To date, KyoAni has mainly been relying on veteran director Tatsuya Ishihara to take care of shows like Phantom World. The result so far has been lukewarm at best.

KyoAni’s team is great at producing human drama, but lack the versatility for other genre-topics. And this is only a weakness that tends to show itself when a project like Violet Evergarden appears. On one hand, the story is a human drama, which fits right into the hands of the talent at the studio. On another hand, there’s also ingredients of espionage thriller, political discourse, and full-on combat sequences that are planted within the roots of its human drama. Most of these ingredients are cooked with a temperature that doesn’t balance well with the stronger human moments that surround them.

“I want to understand what ‘love’ means.”

There’s a great story inside this series, and it shines in enough moments to make Violet Evergarden a rewarding watch. As with any other KyoAni project, the scale in production value is astounding. Akiko Takase’s move from light novel illustrator to character designer and chief animation director is seamless, bringing designs that are both beautifully detailed and flexible enough for clean animation. Evan Call has his breakout hit, with one of the most moving scores in TV anime history. The soundtrack has a life of its own, breathing with a self-assured orchestra of strings, and even using the sounds of a typewriter to enhance its musical personality. This successful mixture of fantasy, history, and fervor is likely the most memorable element from the series. Yui Ishikawa embodies the transformative role of Violet; her fluid range from stale to tender sold the empathetic character. The accessory designs by Hiroyuki Takahashi and Minoru Oota bring the world of the story to a level of detail that’s rare to witness, even in theatrical anime.

This series, in terms of production and narrative direction, has perhaps been the largest challenge for the team at Kyoto Animation thus far. From the thickly detailed rhetoric of the light novel, to the studio’s already highly established reputation, the need for an epic visual scale feels inherent (which the in-house team did an amazing job at meeting/surpassing expectations). However, when it comes to the story’s genre-ambitions beyond “the human drama,” a light shines on the lacking range of KyoAni’s storytellers and directors. The studio can easily charge forward with their primary focus on slice-of-life dramas, but when more narratively-grandiose projects like Violet Evergarden come around, hopefully by then someone from the studio’s newly trained school of directors and animators can tackle them with the right weight and balance.

Of course, not every flaw in the show is due to this one particular element; there are several plotlines and anecdotal choices from the source material that are also problematic as well (Violet parachuting off a single-engine plane and immediately fighting a platoon of soldiers after landing seems questionable at the very least), taking away the emotional impact from genuinely powerful surrounding moments. But what’s important is having directors who know what to take from the source material and what to leave out, a fundamental decision for every adaptation. While Yamada and Fujita have shown evidence of this flexible skill, Ishidate has seemingly yet to find his eliminative ability. Albeit, of everything mentioned before, there’s a lot of growth among the KyoAni team that’s shown in this show; most importantly, it’s a message to its audience that the studio is now readying to tackle stories that touch a larger scale of tones and moods. The decisive component to this is what will the team and studio work to improve on in future projects, after having seen what worked and what didn’t in Violet Evergarden.

In the end, despite its lapses and misses, there’s an everlasting story about love. Not solely romantic love, but a love that brings people together from two edges of the universe. Fujita — with her characteristic blunt fist — paints love not as a social utility, but something that is innately human and unavoidable. With love comes pain, and in that pain is something beautiful.

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page