A lonely death. A cloud of falling angels. A pair of outstretched arms. A barren world of dust. It is fitting that Devilman Crybaby begins and ends with these scenes of isolated destruction. It is a story about many things – the myriad forms of love, the physical and emotional changes of adolescence, the ways in which we succumb to fear and suspicion; but the through-line of the show’s events is Ryo’s failure to learn communal love. His obsession with Akira alone, combined with a complete lack of empathy for anyone or anything else, is the source of his failure to escape the eternal cycle of death and rebirth. For as long as he is unable to break his ties he will be forced to endlessly relive the heartache of losing Akira.

But these apocalyptic visuals are not purely used for dramatic effect. More than set-dressing or a cheap twist ending played for shock value, the nature of the Armageddon is as personal as it is biblical. The visuals are intimately entwined with Devilman Crybaby’s moral themes. The grandiose metaphor of the End Times is linked with the humble scope of the high school track team. These are wedded by an interweaving of Buddhist thought on karma and release. As disparate as the various ideas may seem, they are inextricably linked with Ryo’s personal journey – one of cycles, love, and escaping his own self-imposed limitations. This is Ryo’s story, but in order to understand it, we must grapple with Revelations, samsara, and relay tracks in equal measure.

For all of his cold, calculating exterior, Ryo is a person tormented by what he desires but cannot have. Even though he is capable of loving Akira, it is his unwillingness to love anyone or anything else that taints this and turns it into a force so cruel that it ends the world. This is why Ryo will slaughter people for spectacle, incite worldwide paranoia in his schemes, and even threaten to kill a sick kitten with a box cutter.

Because of his singular obsession with Akira, he is not satisfied with anything less than an equally dangerous obsession in return. For Ryo, love has become a zero-sum game between himself and all of existence; in his mind, he believes that Akira must choose between “Ryo” and “everyone else in creation.” He lacks the perspective to understand that Akira can feel deeply for both. Because of his narrow-minded view, he recklessly pursues the goal of a world scoured of anyone but the two of them, and in doing so kills his love in the process. By closing himself off to the true complexity and diversity of communal love, Ryo doomed himself to a dangerous and all-consuming desire.

Anything for You

It is telling that he spends so much of his time in emotional and physical isolation throughout the series. Ryo is ensconced in his stark white apartment without companionship. He oscillates between monitoring his social media feed and idly browsing through images of his youth with Akira. In these photographs and videos, young Akira and Ryo frolic alone in a world blanketed in white – a cold, dead world where they only have each other for company. The apocalypse is not an expression of some inner lust for bloodshed and carnage on Ryo’s part.

In truth, for all the colorful bombast and messy destruction that takes place in the series, Ryo is ultimately pursuing a stark white world cleansed of anyone but himself and Akira. Ryo seeks to violently break the world that from the broken pieces he might create a tranquil place to share with Akira.

Hence the endless cycle that Ryo finds himself trapped in. The entire narrative arc of Devilman Crybaby is, in fact, one rotation of a cyclic loop. The story begins and ends with the destruction of the world, but this is not the first nor last time this occurs. With each cycle, a new moon is born from the ashes of the old, and a new Earth as well, continuing a grand cosmic process. It is in this repetition that we can discern the heart of the story – one of Ryo’s journey to self-discovery and release.

Ryo states explicitly that he is Satan, the Biblical fallen angel who incited humankind’s rebellion and brought about the end of the Garden of Eden. He is shown to possess magnificent power over the physical world and serves in many of the pre-ordained roles of the anti-Christ detailed in the book of Revelations.

But reading this work strictly through a Biblical lens misses a crucial element of Devilman Crybaby – more than being simply Satan, Ryo is also an asura.

Many in One

While one could interpret the show entirely through a Judeo-Christian perspective, there are significant challenges to doing so. Even ignoring the titular Devilman for a moment, there is the complete omission of the messiah figure in the end times (a rather important part of the story), and the cycle of rebirth discussed earlier. Generally speaking, the idea of a cosmic cycle is not native to the Judeo-Christian tradition, but rather is more common in systems such as Buddhism and Hinduism. In these traditions, one can find the idea of karma, which dovetails nicely into Ryo’s personal journey.

Sometimes karma is thought of as a sort of ledger. ‘Good’ karma is added to a person’s spiritual balance, and ‘bad’ karma is subtracted from that balance, similar to a cosmic accounting system: if you are a ‘net positive’ then good things will happen. Perhaps a more apt view of karma is that it is our ties to the people, places, and things of this world. Karma represents our desires, both positive and negative; the more we desire something, the more we are tethered to it and the more control it exerts over us. The greater our karma, the more attached we become to this world and its separations, its divisions, its false pretenses. The more karma we have, the more willing we become to enact drastic measures to pursue those desires.

While negative desires like dominance over others or lust for wealth are easy to understand in this light – people who cause harm to others over control and greed are in ready supply – even ‘positive’ desires can have this effect on us. Loving your significant other and wanting the best for them can create a karmic tie so strong you would harm others to keep them safe. The desire to protect an ideal can lead you to harm anyone who would challenge it. Wanting to protect your child can drive you to shelter them from needed experiences and growth. In this understanding, the more we desire the things of this world, the more attached we become to them. As such, we cannot achieve enlightenment and separate ourselves from the cycle of birth and rebirth known as samsara.

Here is where Devilman Crybaby lays its cards on the table.

Round And Round

The key is that Ryo’s lesson is one of two traditions, a mixture of ideas. Until he can break free from his karmic ties – his overwhelming obsession with Akira and Akira alone – and embrace a broader empathic love for all living things, he will be eternally trapped in the cycle of birth and rebirth. It is this fusion of many traditions that help make the tale so compelling. Incorporating the concept of birth/rebirth cycles as well as a communal understanding of interconnectivity and love makes for fertile ground to tell the story of Ryo’s personal journey.

He would do anything for Akira, and in the end, it is this very same obsession that kills Akira. Ryo cannot escape the cycle of samsara until he separates himself from desiring Akira over all things and instead embraces a unifying love of Akira and all things. Ryo has created walls, separated himself, and become engrossed with Akira alone; there is no chance to accept the wider joy of community and connectivity because of the intensity of his love of Akira.

Flawed Together

Ryo is not alone in his karmic ties but he is separate because of his narrow capacity for emotion. Akira, Miki, and Miko all are flawed characters. They, too, cause hardships and use others on their journeys of self-discovery. But the difference between these three and Ryo lies in their understanding that it takes a communal effort to cover up for their inadequacies. None of them runs the race alone. Even if individually they are flawed, their overlapping strengths can fill in the gaps. They know that they are part of a wider web of interconnected loves, hopes, fears, dreams, and relationships. They each have their part to play in the greater good, and so they run the race as a team because in that way they all find joy.

Each of these three has a moment where they make a stand for communal love. For Miki, it is when she implores people across the internet with her words of acceptance for devilmen. Miko does so in the dramatic beach sequence, pressing a gun to her head and pleading with her attackers to just be human even as they move in to kill her for her supposed inhumanity. Akira does so by using his own body to shield suspected devilmen who are tied to stakes, bearing the brunt of the stones and insults that were meant for others.

Even when the world is crashing down around them, they end up begging, pleading, imploring humans to love one another, faults and all. This trio is willing to lay their own lives on the line for what they believe in. They are a trinity that would risk death to convince people of the need for communal love.

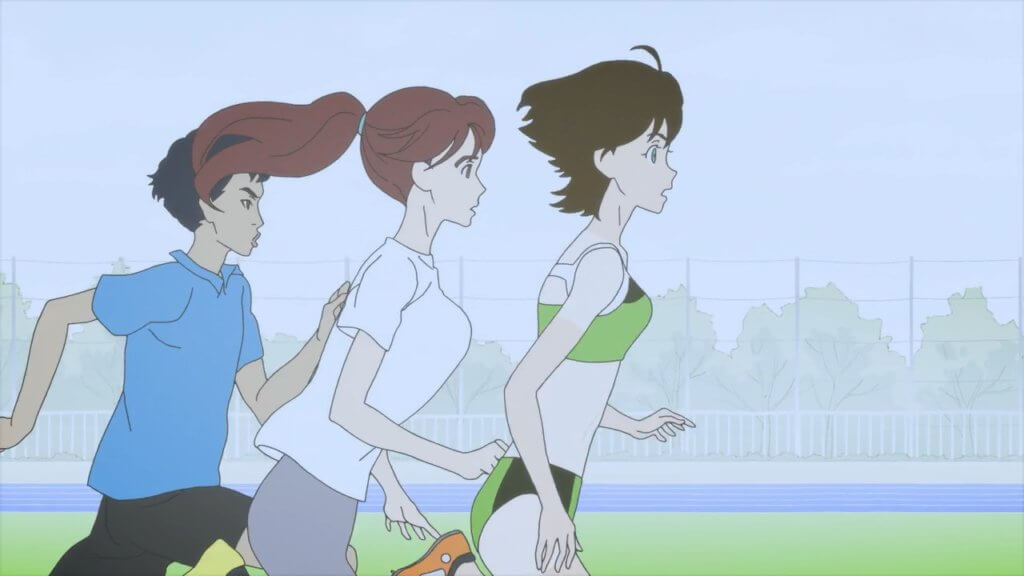

Yet Ryo cannot accept the baton they offer. Again and again, we see Akira, Miki, and Miko running on the loop of the race track, passing the baton to one another. Certainly, they each have desires: romantic interests, competitive drive, longings for others. But they also have the ability to love others, to have friendships and familial connections, to break free from compulsive obsession over a singular entity, and instead give themselves over to a broader understanding of compassion and acceptance. They can run the race freely, passing the baton from one to the next.

In perhaps the most beautiful imagery in Crybaby, they find the joy of cooperation and community through accepting one another by running these relays together. They accept themselves and others completely and they can pass that love forward by letting go of their singular tie to it. This compassion allows them to run the race freely and become part of something that is more than their individual selves.

But when the time comes to accept that love and openness, Ryo rejects them; time after time we see the baton clatter to the ground in the final flashback sequences of the show. He finds himself incapable of opening up to that kind of vulnerability. In accepting love from so many others, Ryo will be forced to allow people beyond Akira in and pass that love on to even more people – thereby relinquishing the singular control he desires. Ryo will only be able to escape the cycle of samsara and find true peace when he realizes that loving Akira and loving others are not mutually exclusive.

Until then, the end of the cycle will be the same every time:

Ryo wept.

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page