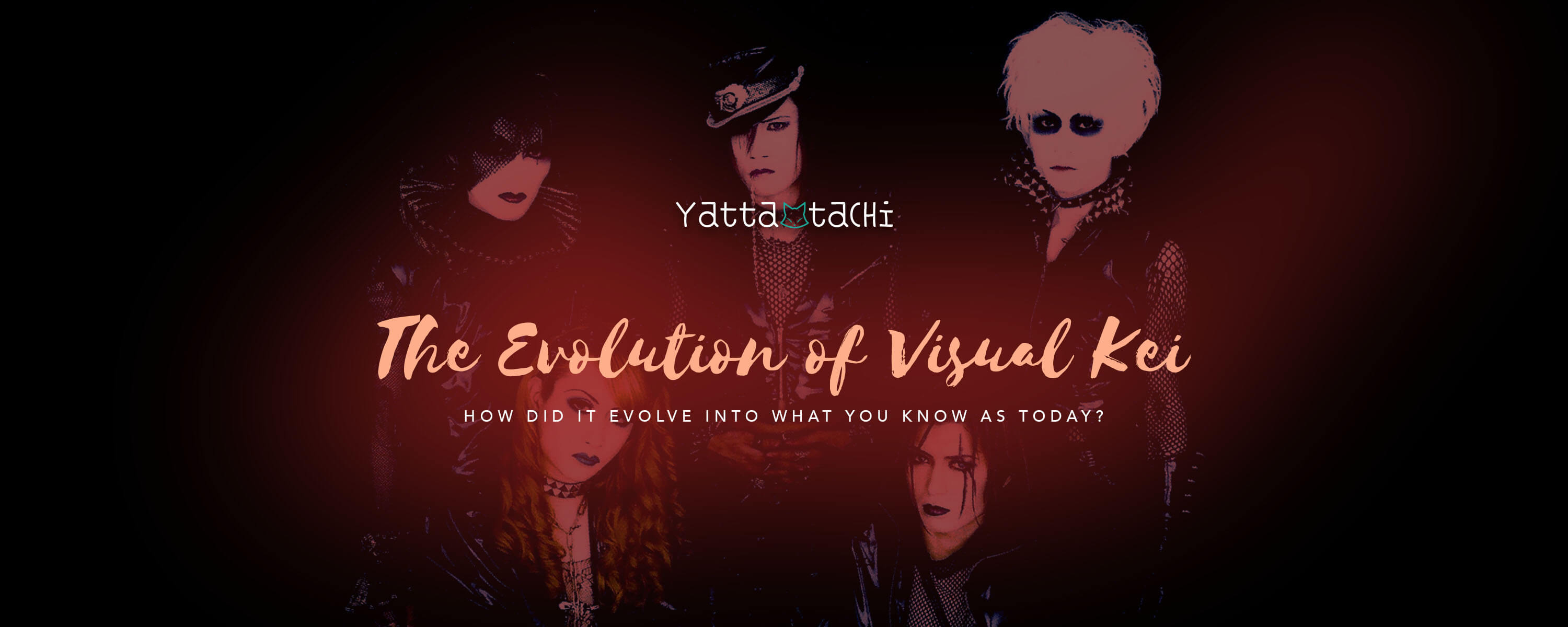

The date is March 4th, 2017. Thousands of fans from all over the globe are assembled a the SSE Wembley Arena in London, UK. What they all have in common is a passion for Japanese rock, more specifically, for the biggest band to have emerged out of Asia. And they all have been good and thoroughly X’ed. When asked the surprisingly common question “What, rock music exists in Japan?,” they can vouch for it. And then some. The band in question is named X Japan, the creators of a multi-layered musical genre which has developed and conquered decade after decade and generation after generation. The genre is called visual kei, and this is a brief overview of how this obscure genre came to be.

Formalities first. Visual kei (ヴィジュアル系) literally translates into “visual style”, and is a musical genre, as well as a form of fashion, deriving from the musical influence. In visual kei music, the visual is as important as the sound. What you see on stage is tied closely to what you hear.

Generally, the term is associated with androgynous looks, larger than life hair in all colors of the rainbow, eccentric and unreal outfits, which are just as likely PVC or leather and aristocratic fashion with platform shoes. It is also characterized by para-para; a form of synchronized dancing set to certain lines of the music and often choreographed by the fans themselves, dramatic stage shows and heavy guitar riffs.

When trying to explain the concept in western terms, definitions such as ‘glam rock’, ‘shock rock’ or ‘heavy metal’ are often applied. Visual kei however, is none of these, all of these, and everything else. Today, the genre features a variety of sub-genres and so-called ‘mini-movements’, and the definition of what is and isn’t to be considered as visual kei (or VK) seems to vary between bands, fans, and scholars alike. The reason for its versatility and self-contradictions may be found in its history and origins.

1980s: The Origins of Visual Kei

Long before X Japan sold out the Tokyo Domes 18 times and went on to conquer the world, they were a band consisting of two young boys from Chiba Prefecture – Yoshiki Hayashi and Toshi Deyama. At the Wembley Arena show in 2017, Yoshiki told an amused audience of the origin of their name, explaining that they had no name, and decided to call themselves “X” for the time being. After finding out that the letter “X” could be a symbol for infinity, they kept it. Japan at that time was beginning to open up more to western influences, and the young duo found themselves enthralled by Western music. The classically trained Yoshiki went on to listen to Kiss, Sex Pistols, David Bowie and Queen, influences which all went into X’s music as the band began writing their own songs.

In 1989, they made their major debut, and a major impact on the Japanese market, aptly described by the band’s own slogan: “Psychedelic violence crime of visual shock”. Three years prior, Yoshiki had already set up his own record label; Extasy Records. As a way of promoting the bands signed to the label, ‘Xtasy Summits were held annually starting in 1988; music festivals where the bands would perform together, often covering each other’s music or music they had been influenced by.

Meanwhile, Dynamite Tommy, vocalist of the punk band Color, set up another label named Free-Will. These two companies combined produced a variety of massively successful bands and gave the Japanese visual kei scene a strong foothold right from the beginning.

At the time, Japan’s youth culture had been under development and was already influenced by western culture, American culture in particular. However, the saying “the nail that sticks out, must be hammered down” was strongly anchored in Japanese society, largely considered to be of the most uniform nations of the world at the time. Yoshiki recently related to Newsweek that X Japan’s elaborate hair was something they had come up with themselves – having no clue that it was associated with overseas metal acts.

While the youth of Japan listened to overseas rock and pop music, strict conventions prevented most youths from dyeing their hair and copying their idols’ flamboyant style. Many therefore see visual kei as a rebellion against the strict expectations and conformity of Japanese society and gender, together with other forms of expressions and fashion, such as cosplay and lolita, which both are also closely tied to the VK movement.

Many visual bands adopted an androgynous and feminine form of dress and expression. In X Japan’s case, Yoshiki told the BBC that the idea to dress feminine came to him after being approached by an agent who felt that X Japan’s aggressive, speed metal type music should be accompanied with military-style clothes. “So I did the exact opposite! We were rebelling against everything!” Yoshiki said laughing.

The 90s: Grandeur and Decline

The 1990s are considered to be the great decade of visual kei. It is also a decade which shows the enormous diversity within the genre, from speed metal and power ballads, to aristocratic tendencies and cosplay-bands.

In 1991, Luna Sea (Lunacy until late 1990) were signed to Xtasy Records. While their effeminate looks and big hair were reminiscent of X Japan, their sound was less aggressive, and more melodious. The five members of the band all had different musical influences: Ryuichi (Vo.) and Shinya (Dr.) tended towards pop music, while Sugizo ( Gt.), Inoran (Gt.) and J (Ba.) preferred rock. Additionally, Sugizo’s violin gave another dimension to their unique sound. Over the course of the decade, they would tone down their appearance to appeal to a more main-stream audience. However, they are still credited as being one of the biggest influences to later visual kei bands.

This period also saw the rise of what some fans refer to as The Four Heavenly Kings ( an expression inspired by Buddhist beliefs): Shazna, La’cryma Christi, Fanatic Crisis, and Malice Mizer. These four bands dominated the latter half of the 90s, and also had great influence on the visual scene, and continued their activities well into the 2000s.

Malice Mizer is likely the best known of these four, especially outside of Japan. From their debut in 1992 until their indefinite hiatus in 2001, Malice Mizer covered gothic rock, synth/art pop, classical and dark wave influences through three eras, all of which were represented by different vocalists. Their biggest success was in the years 1995-99, during the so-called Gackt-era. During this time, their music still retained some gothic elements, but featured lighter pop-elements, synthesizers and classical, baroque influences.

This ties into one of the sub-genres that had come into the scene by the mid-90s, known as kote-kote (or kote-kei), which often included elaborate stage sets. There were also stage personas for each band member, often with an equally elaborate backstory, interwoven with the theme of the music or concert. Malice Mizer’s 1998 tour, Merveilles l’espace is an example of this, with their stage being set up as a gothic castle, in front of which the band acted out minor plays or skits according to their roles.

During the performance of Le Ciel, for instance, Gackt, costumed as a fallen angel, would descend onto the stage from above, perform the piece in dramatic fashion, before ascending again. As a solo artist in the 2000s, Gackt would later perfect this form of visual expression through his concept of VISUALIVE. Guitarist and band leader Mana also had a profound influence on lolita fashion, and eventually started his own brand; Moi-meme-Moitie.

Another massive act that came out of the 90s is Dir En Grey, who formed in 1997. Releasing their debut album Gauze in 1999, they had already made an impact on the mainstream audience by reaching the Oricon Top Ten. Although some tracks, like Cage had an almost pop-esque sound, the band also presented darker themes, not least in their music videos where the content definitely presented its share of shock factor. Dir En Grey would go on to become one of the biggest Japanese band names outside of Japan, although they have since discarded their visual label and fluctuated towards a different sound, for instance incorporating elements of Nu-Metal into their more recent music.

*Video below contains violence, blood, and sexual themes*

Like visual kei itself, the 90s are difficult to write about, due to their ambiguity and the large diversity of bands and sub-genres. It’s hard to only mention a few, or to find one red thread tying it all together.

By the late 90s, the ambiguity was complete: it saw the start of some of the most well-known visual acts and artists, but was also the end of an era in many ways, with some of the most iconic bands breaking up. While others left the genre to pursue different styles and a mainstream audience. X Japan had split in 1997, and lead guitarist hide passed away that following year. Malice Mizer’s drummer Kami passed away from a cerebral hemorrhage, and vocalist Gackt had left the band. In 2000, Luna Sea and Shazna both disbanded, and several other landmark bands followed suit over the next few years.

Additionally, visual kei had never quite made it to the big leagues; despite hordes of loyal fans and sold-out tours and venues, the genre remained somewhat obscured from the mainstream media. When the new millennium rolled around, the feeling that visual kei was passé was beginning to take root amongst some.

The Birth of Neo-Visual Kei and New Influences

Interestingly, the 2000s also saw a revolution in the genre, contradicting the belief that visual kei was over. The new millennium saw the growth of what is frequently referred to collectively as “neo-visual kei”, as well as an explosion in western interest for Japanese culture and entertainment.

Neo-visual kei might be even harder to categorize than its predecessors, as it encompasses even more styles, influences, and sounds. Fashion-wise, the neo-visual bands often appeared more groomed than their predecessors. While still sporting edgy, spiked, and dyed hairstyles, piercings, and leather hotpants, their looks often seemed less haphazard, and more colorful and coordinated.

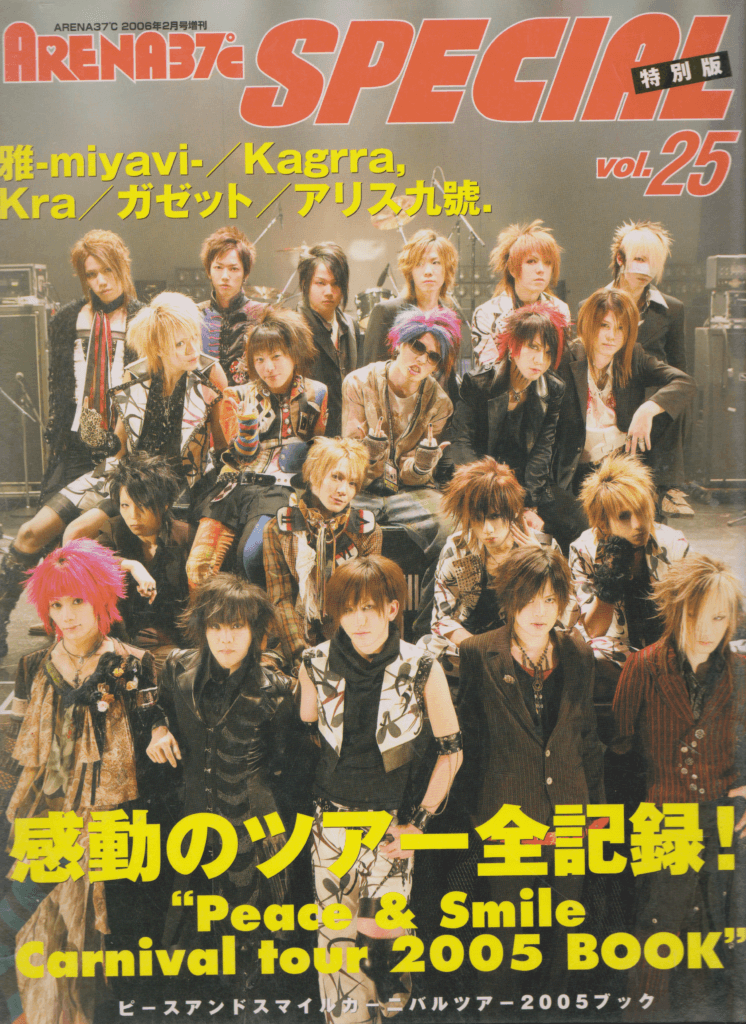

A pioneer for the term was the label PS Company, a sub-division of Free-Will records. In the early 2000s, PSC fronted Alice Nine, Kagrra, Kra, The Gazette, and Miyavi (co-managed by Universal Music Group). These bands in many ways sum up the essence of the early neo-visual days; The Gazette, who along with Miyavi would go on to be the most successful overseas, represented the heaviest sound on the label, with songs like Ogre, bordering on metal.

Alice Nine also had their share of heavy guitars and growling vocals but were more on the melodious side. Kra’s early days were full of asymmetrical, colorful costumes and a mix between positive, pop-ish music, and heavier songs which clashed with their overall fairy tale (“Meruhen”) theme. Meanwhile, Kaggra, stood out, as a band who incorporated traditional Japanese musical instruments like koto into their songs and dressed in predominantly traditional Japanese clothing, reminiscent of earlier kote-kei bands. Kaggra’s music represented a more traditionally Japanese, melodious, or melancholy form of sound than their fellow PSC-bands.

The final artist to go on the Peace and Smile Carnival Tour of 2005 with the label was multi-talent and guitar-wiz Miyavi. Miyavi had previously been a guitarist for the visual kei band Dué le quartz from 1999 until their disbandment in 2002, under the name Miyabi. In the early 2000s, Miyavi was most known for his quick-paced guitar play, heavy rock riffs in songs like Gariben Rock and Rock no Gyakushuu -Super Star no Jouken, and hyperactive stage presence. However, over the course of the coming decade and into the 2010s, his form of expression both musically and visually changed and evolved multiple times.

He developed the concepts Neo Visualizm and Samurai Guitarist, and eventually set up his own record label in 2010, J-Glam Inc. Although Miyavi, like many other visual artists, has toned down his appearance, he has in no way left the visual business, but rather claims to be building on it and spreading it to the world through new forms of expression. To talk about Miyavi’s visual and musical feats is a whole article in itself.

Simultaneously as PS Company did the world in with their varied forms of visual rock music, another sub-genre was coined; oshare-kei (Stylish-style). There seems to be some varying opinions on what this really entails and where it came from, but the general consensus amongst fans seems to be that bands with smashingly colorful style and plenty of accessories who played an upbeat, pop/punk variety of rock music fit into this genre. Bands such as An Café and SuG go into this category, mixing both bubbly pop tunes and energetic, heavy sounds. Particularly in their earlier days, before the departure of guitarist Bou, An Café were on the heavy side and were often fronting visual clothing brand Sex Pot ReVenGe. Since 2006 however, their sound fluctuated more towards what they themselves have termed Harajuku Dance Rock, with less growling vocal and more synth-pop incorporated in their music.

Parallel to the evolution of this form of neo-visual expression, bands like Versailles and D continued the tradition of kote-kei, and aristocratic grandeur, but gave it their own style by sometimes adding elements such as steam-punk or “horror-visual.”

All the bands referred to up until this point have been all-male, despite their androgynous looks and often gender-bending stage persona. However, this does not mean there are no female visual groups.

In 2003, two all-female groups; Danger Gang and Exist Trace burst onto the Japanese music scene and quickly established large fan followings. Exist Trace, in particular, has had great success overseas, touring both Europe and appearing at various conventions in the US, in addition to appearing on the 2007 Silent Hill soundtrack. Their sound has been defined as alternative- or gothic-metal, or even death metal.

Globalism and resurgence

After 2005, with the establishment of sites such as YouTube and MySpace, it became easier for audiences both at home and abroad to access news and information, music videos and other clips, as well as for the artists to expose themselves to a new and larger fanbase. This largely explains the massive following of visual kei bands in Europe and the Americas, and might also be why neo-visual bands seem to be popping out of the ground these days; with new bands emerging on a regular basis. It is not uncommon in the west to see bands who claim to be inspired by Japanese musicians, and in some cases even label themselves as visual kei, such as Swedish bands Seremedy and Kerbera, or German Kogure.

However, despite this, visual kei remains an underground genre internationally, as well as in their native Japan, and only a handful of bands are ever seen on mainstream music programs or featured in other magazines than publications such as Cure or SHOXX, which focus on these types of bands.

Still, looking at how the genre has evolved and developed since the early 1980s, there is no knowing where it will go from here, and if it will continue to be obscure. In 2007, legends X Japan reunited, after ten years of separation. Following them, Luna Sea, Siam Shade, and several other influential bands from the 90s have reunited and resumed musical activities, touring both nationally and internationally. Their fan bases and reach are bigger than ever.

The visual kei of the present is often critiqued for not being what it used to be, that the neo-visual scene is all about mass-production of bands, rather than the music and the spirit. However, as I hope to have shown through this somewhat limited – as it must be in such a diverse genre – selection of artists and music, there doesn’t seem to be any right or wrong answer to what it means to be visual kei, how it is supposed to look or sound like, or which purpose it is supposed to have.

In any case, I think it is safe to say that visual kei can be many things, but visual kei is not dead.

Sources: Timeout, BBC Outlook, Excite music, Newsweek, Scientific Journal of Humanistic Studies 5.9, We Are X documentary

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page