Alcohol is a universal constant. Nearly every country on Earth has alcohol and a culture that surrounds its consumption. I’m something of an expert on drinking culture in America because I regularly take part in it. And as an aficionado of most things Japanese, I’m interested in their drinking culture too.

The US and Japan have fascinating histories with alcohol, and both countries have influenced each other over the years. So what, specifically, do they have in common when it comes to that sweet, sweet nectar of life?

To really understand the drinking culture of each country I think it’s important to have an understanding of how they got to where they are today. American alcohol culture owes quite a bit to European alcohol culture. In Renaissance Europe, to drink alcohol was to appreciate one of God’s many gifts, and to abuse it was sinful. It was also a hell of a lot safer to drink than water due to its sterilizing nature. Because of this, pilgrims and explorers tended to take more booze than water on their ships. It was the arrival of Europeans in the New World that planted the seeds of modern drinking culture in America.

The way those seeds grew, though, was thorny. By the turn of the 20th century, alcohol abuse began to be seen as both a symptom and a cause of political corruption and lax attitudes toward religion. Come 1920, enough people bought this idea that a total prohibition on alcohol was enacted. It had some unintended consequences, namely that it jump-started organized crime, and so it only lasted 13 years. But its effects, like a strong stigma against alcohol abuse, a minimum legal drinking age, licensing laws for businesses that manufacture and sell alcohol, and a flagrant disregard for many of these laws, last to this day.

The history of alcohol in Japan is a bit less complex. According to this article, there are Chinese texts from as early as the 3rd century that refer to Japanese people drinking heavily. The Japanese had been brewing and drinking sake, which is basically rice wine, as well as spirits made from fruit, for a long ass time. Beer, however, didn’t arrive until the 1700’s, accompanying Dutch traders. Some of Japan’s biggest beer brands (Asahi, Kirin, Sapporo, and Suntory) today got their start in that time period. Without the Prohibition-related emotional baggage to slow the party down, Japanese laws related to alcohol tended to be more lax.

Unsurprisingly, dramatically different histories with booze resulted in dramatically different attitudes towards it. In America, underage drinking is so ludicrously common that most people think it’s weird if you never drank in high school. And even though most college students are underage for the bulk of their time there, so much drinking goes on at American universities that some schools are famous for their debauchery. There are whole websites devoted to ranking the top party schools in the nation. We also make entire movies about high school and college kids getting wasted and having life-changing good times. In short, underage drinking is essentially a rite of passage in America, practically a part of puberty at this point, and we glorify the hell out of it in our media.

In Japan, underage drinking is not unheard of, but it’s viewed much differently. It’s way easier to get alcohol as a teen in Japan than in America. In the US, you need either a fake ID, a 21-year-old friend, or cool parents. But in Japan, supermarkets and convenience stores will sell alcohol to kids because they know they’d never drink it. That’s against the law, and the idea of the law holds a lot of sway in Japanese culture.

Japan is so relaxed about carding people that they even have alcohol vending machines. Although they’re not nearly as ubiquitous as they once were, you can still find them here and there in major cities, and absolutely anyone can buy from them. There is no ID check, and rarely are there cameras watching them. Again, it’s the threat of the law that supposedly prevents kids from cracking open a cold one with the boys right there on the side of the road.

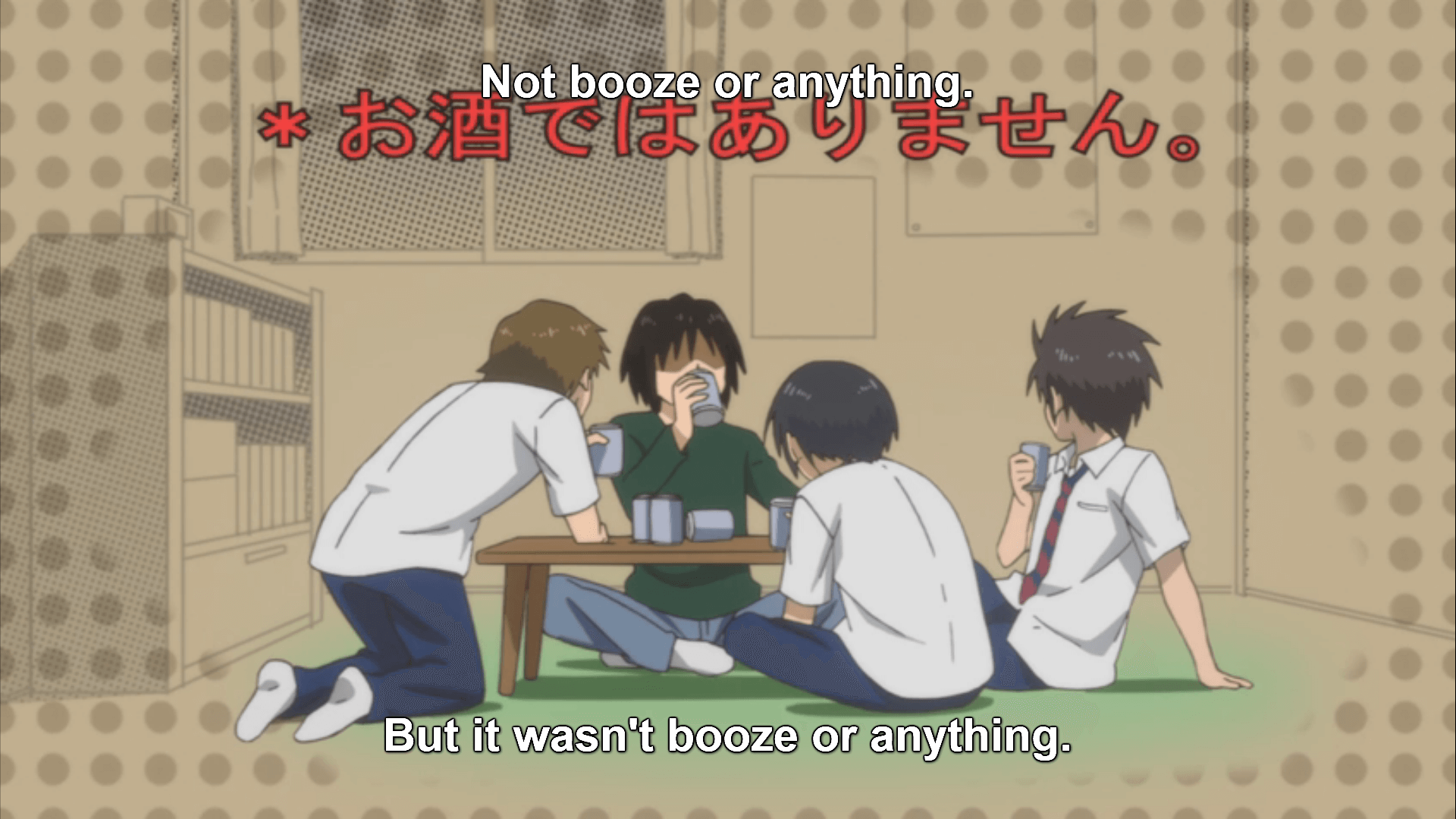

It probably also helps that Japanese media goes out of its way to NOT glorify underage drinking. Anime, manga, and movies will often have young characters acting drunk from drinking too much juice, or from eating chocolates with trace amounts of rum in them or something.

But actually portraying underage drinking is kind of a no-no. “This isn’t really beer” and “don’t let kids drink” disclaimers are a common sight alongside drunken gags in high school comedies. All of this is not to say that underage drinking never happens in Japan. It absolutely does, it’s just more frowned upon than in America.

Once you’re legal, especially in the college environment, the two drinking cultures converge to an extent, but not entirely. Drinking is very much a social activity in both America and Japan. Parties ranging from intimate gatherings of a few friends to out-of-control ragers occur in both countries.

America seems to win in average size though. The stereotypical massive frat parties, which happen every weekend at some US schools, don’t really have a counterpart in Japan. The Greek fraternity/sorority system, in all its cross-country, debauchery-enabling glory, doesn’t have a foothold there.

But Japan does have what they call “circles”, which tend to have fewer members than American frats, and function something like a cross between a school club and a frat. They’ll often have themes, like a sport or some aspect of academics. They also have a lot of drinking parties, which are typically called nomikai (or sometimes konpa for ones that take place specifically in university.)

These take place at pub-like restaurants called izakaya that often have private rooms that can be rented for exactly this purpose. Nomikai and konpa are technically circle activities, supposedly to facilitate bonding among members. But make no mistake, their main purpose is to give you an excuse to drink with your friends.

“So Bill,” you might be wondering, “if both countries have these college societies that drink, are there actually any differences between them? They sound basically the same.” Well, the main difference is exactly how alcohol ends up in your cup. Circles have a rigid hierarchical structure (like most parts of scholastic and professional life in Japan), and more senior members (the senpai) pour the younger members’ (the kouhai) drinks. Glasses are never empty and the pressure to drink everything poured for you is incredibly high. Binge drinking is essentially mandatory at nomikai.

In the US, binge drinking is common, but not because of any structurally reinforced societal expectations. Frat parties are considerably less private than circle parties, so once the general public is around, any hierarchies within a frat tend to break down. Everyone is more or less equal, and often drink from communal sources likes kegs, 30-packs, or mysterious and potentially dangerous punch bowls.

The key difference is that at American college parties, you’re mostly filling your own cup. The peer pressure to drink heavily is of course still there, but the self-serve nature gives you some control over how much you consume, and you won’t be disrespecting your seniors by drinking responsibly.

The phenomenon of the nomikai carries over into the post-university workplace too. In America, alcohol and work don’t mix. You might have a glass of champagne to celebrate a major deal coming through, but even a single drink at a business lunch or dinner is rare.

In Japan, drinking parties after normal work hours are common, and sometimes meetings are drinking parties. And while you may not be on the clock at these parties, there is pressure to still be “on” and in work mode while there. That said, things said while drunk at nomikai are never spoken of again. So if you have problems with your boss, here’s your chance to tell them.

Japanese society also enables these drinking practices by being so damn safe all the time. Japan has an extremely robust public transport system, which means drunk driving incidents are very rare. And if a businessman passes out in a puddle of barf on the train or on the side of the road, as they frequently do, they’re unlikely to be attacked, harassed, or stolen from. You could never expect that level of safety in a big city in the US.

But all these years of drinking take their toll. According to a 2003 article from the American Psychiatric Association, the rate of alcoholism in most developed countries is declining, but it’s actually getting worse in Japan. The thing is, they’re not doing a whole lot about it. In America, there are rehab centers just for alcoholics and hospital space specifically for alcohol abusers. Alcoholics Anonymous and other support groups are well-known. We treat alcohol like a drug.

In Japan, they don’t. Most hospitals don’t dedicate more than a couple beds to people with addictions, and there are very few rehab centers. Most Japanese people don’t consider others to have a drinking problem unless they get violent. This Japan Times article refers to a 2013 survey by a Japanese Health Ministry research team which states that, at the time, about 1.09 million people in Japan were alcohol abusers, but only 40 to 50 thousand were receiving treatment.

But all this doom and gloom talk is getting in the way of something all drinking cultures, not just American and Japanese, share – there’s something about alcohol that brings people together. In every country, there is a social element to drinking. It strengthens bonds. It bridges gaps.

And what better way to bridge a gap as large as the Pacific ocean than by drinking foreign brews? If you’re of age and live in America, go find a Japanese restaurant and get some hot sake. It’s delicious. I promise you won’t be disappointed, and it might open your eyes to another culture. And if you live outside of America, go to a convenience store and buy the cheapest tallboy you can find for that true American experience. But don’t get your hopes up. And remember, always drink responsibly!

Sources

Milne, David. “Japan Grapples With Alcoholism Crisis.” Psychiatric News, American Psychiatric Association, 5 Dec. 2003, http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/pn.38.23.0012

Ashburne, John. “Drinking Culture in Japan.” Drinking Culture in Japan, Japan Visitor, http://www.japanvisitor.com/japanese-culture/drinking-in-Japan

Ito, Masami. “Dealing with Addiction: Japan’s Drinking Problem.” The Japan Times, The Japan TImes, 30 Aug. 2014, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2014/08/30/lifestyle/dealing-addiction-japans-drinking-problem/#.WgqIIIhrxPY

Sakamoto, Kay. “Why Drinking With Coworkers Is So Important In Japanese Work Culture.”GaijinPot Blog, GaijinPot, 14 Nov. 2015, https://blog.gaijinpot.com/japanese-drinking-culture/

Salvaggio, Eryk. “On Drinking Too Much in Japan.” This Japanese Life., 9 May 2012, https://thisjapaneselife.org/2012/05/09/on-drinking-too-much-in-japan/

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page