Akane Kuchinashi and Suzume Kikuo are childhood friends and neighbors. Akane is a quiet, gloomy kid who considers himself prone to selfishness and laziness. Suzume is beautiful, popular, and kind. One day Suzume asks Akane to be her boyfriend out of the blue. He turns her down, saying that going out with someone so perfect would be hard on him. The next day she disappears. Her family and friends try to find her, to no avail. But a month later, Akane finds her while walking home from school. Suzume is not the same as she used to be, though – she made a wish to “become the most miserable thing in the world”, and now she’s a gigantic, fuzzy, jet black caterpillar. And she’s not sure it’s possible to turn back, even with the help of fellow high schooler/local forest deity Yutaka Ouga.

Author Sanzo is better known in the west for their series My Girlfriend is a T-Rex, a short, lighthearted monster girl romance. Monstrous girls and romance is a common thread between the two series, but otherwise, Caterpillar Girl is a very different book.

The Perfectly Fine

Sanzo has a distinctive way of drawing faces — so distinctive that I recognized that style before I remembered why I knew the name Sanzo. Having said that, the character designs don’t stand out much overall. Akane and Suzume both have totally black hair, the caterpillar has totally black fur, and all the characters wear a lot of blacks and dark greys. Backgrounds are largely non-existent, which leads to many black-on-white panels. The high contrast style is nice to look at, but doesn’t leave much of a lasting impression.

The Excellent

What does leave an impression is the plot and the characters. The story has a fable-like simplicity on its face, but Sanzo deftly uses that simplicity to tell a complicated story with no easy resolution. Sanzo uses Caterpillar Girl’s fairytale framework to explore the unreasonable expectations society has for women and the long-term impact that it can have on them, as well as toxic masculinity and cycles of abuse.

Akane

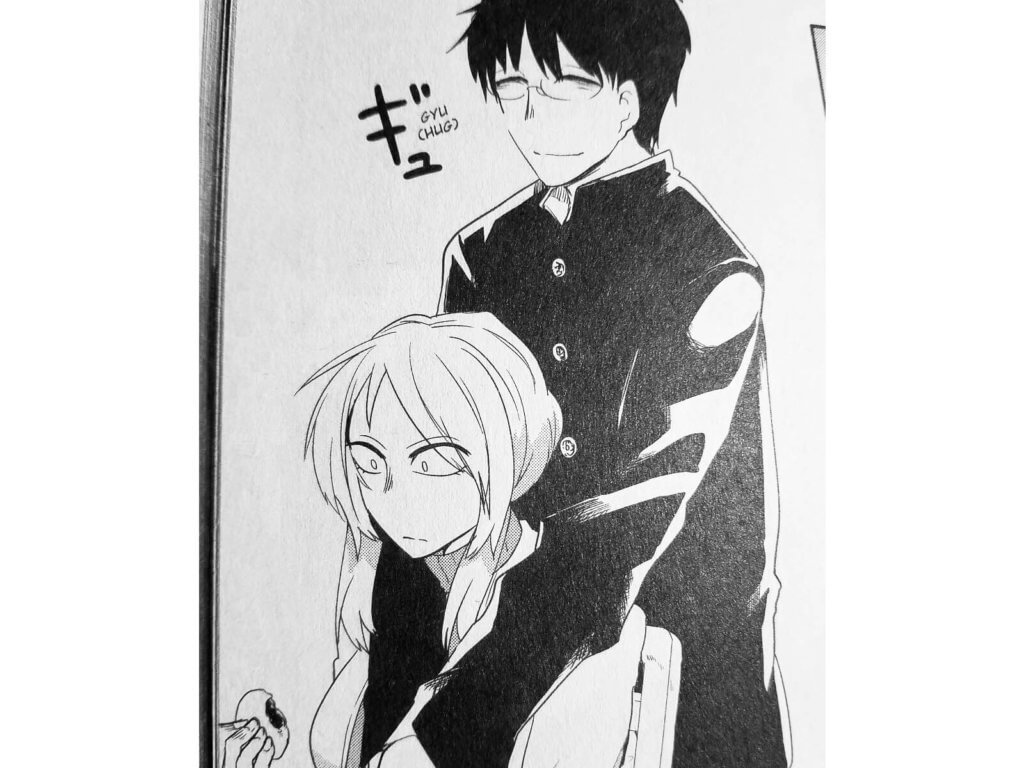

Akane is an example of the damage toxic masculinity can do to men, even fundamentally decent, not “traditionally” masculine dudes. One of Akane’s biggest failings is his unwillingness to talk about or express his feelings. He can’t admit he loves Suzume, which directly, tangibly hurts her, as it spurs her to make her crazy wish. Men are often told that they’re not “real” men if they allow themselves to express emotions, and Akane bottling up his feelings is a textbook example of the insidious effects of that.

But he’s also a victim of a more obvious toxicity himself — Akane’s father beat his mother. Akane and his mother were very close, but their relationship with his father was strained. Akane’s mother was likely cheating on his father. One day, when Akane is only eight years old, his father attacks his mother. She immediately packs her bags and leaves. When Akane tries to go with her, she tells him to stay, knowing that she’ll never be able to provide for a child by herself, but she does it cruelly. He never hears from her again, and while his father never physically abuses him, their relationship is ruined.

His mother’s abrupt departure does more psychological damage to Akane than seeing his father hit her. It affects his ability to trust the people who are supposed to love him, and probably his trust in women in general. Akane’s more insidious misogyny is a direct result of his father’s violent misogyny. But even though Akane is our viewpoint character, Sanzo is careful not to portray his actions as right. It would be easy to slip into woe-is-me, “nice guy” rhetoric here, but Sanzo strikes an admirable balance of understanding without excusing. They sympathize with Akane’s circumstances without sympathizing with his views.

And Sanzo is equally careful with where they place the blame for Suzume’s state. By the end of the book, Akane has come to realize that Suzume’s caterpillar form is pretty much entirely his fault, and that it’s up to him to fix it. Akane’s story arc is one of the most well-realized stories about a man trying to do better by women that I’ve read in ages.

Yutaka

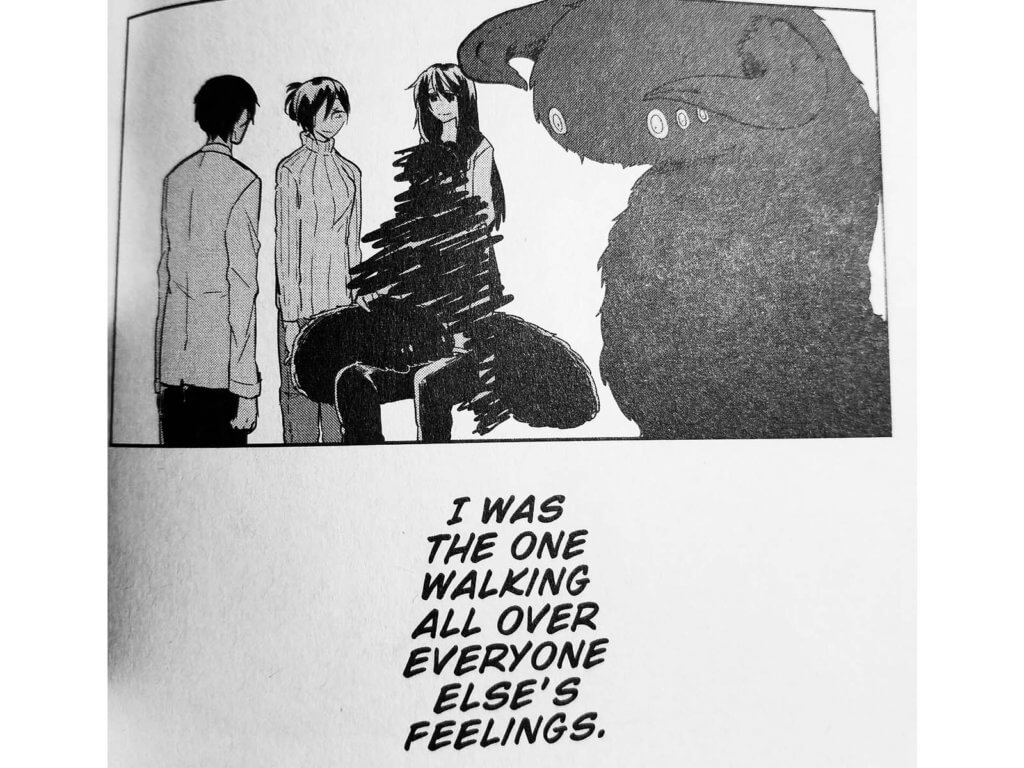

The Yutaka that Akane and Suzume know, the forest spirit, was once a regular human child. She was, as Yutaka puts it, “clumsy and slow to learn”, and nobody paid attention to her. She begins to believe that if she could grant wishes, people might love her. She discovers a spell that makes her a god who can do just that and begins granting whatever wish people make. But the people don’t love her, they just use her for her powers, including to kill. Yutaka keeps granting wishes, and eventually, she finds she’s completely alienated herself, all while transforming into a monster.

Granting wishes is all she knows how to do now, though, so when Suzume comes along, Yutaka turns her into a caterpillar. One thing Yutaka can’t do, though, is reverse wishes she’s already granted, meaning Akane and Suzume have to fix it themselves.

Yutaka is a surprisingly complex character, and a little tough to get a bead on. I appreciate that Sanzo doesn’t let her powers become an easy deus ex machina solution to the central problem. She’s been hurt beyond repair by the people around her using and abusing her. The very thing they used her for is her entire identity. Her sense of self-worth is horribly tangled up with her past.

To avoid having to deal with that psychological Gordian knot, Yutaka decides she’s not going to grant the wishes of people she doesn’t like, which, based on what she’s heard from Suzume, includes Akane.

Here Sanzo shows us a partial solution to the systemic issue they’re grappling with. Yutaka has simply refused to bow down to or even interact at all with the system that had hurt her, and made her hurt others, for years. She’s sparing herself from harm by refusing to play the game, but the game is still going, hurting other people.

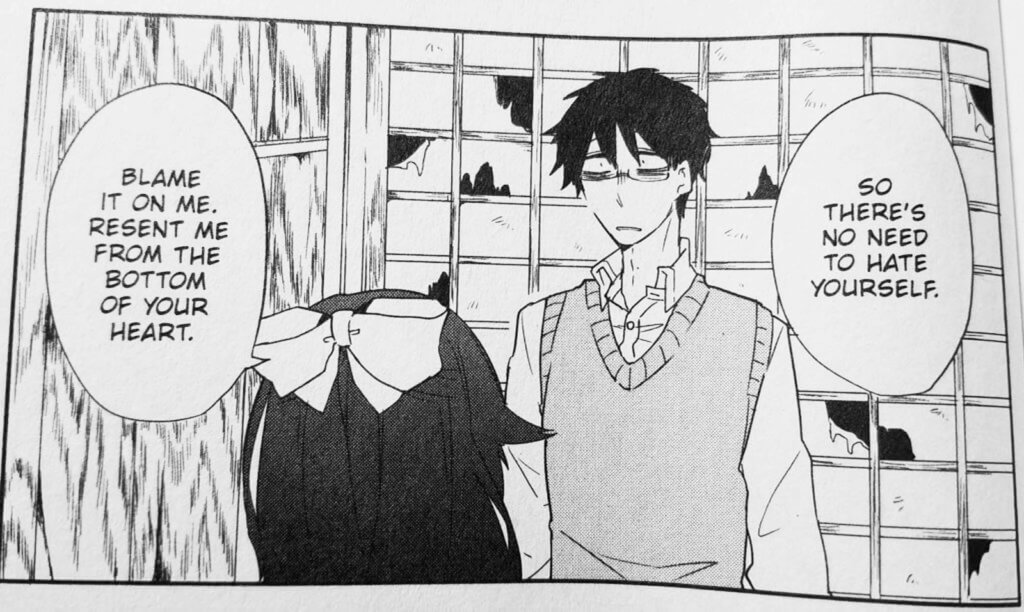

Just like with Akane, Sanzo is careful with where they place blame – for Yutaka, none of this is her fault. Yutaka can’t help but see herself as the villain, but Sanzo takes the time to make it clear she’s actually Akane’s best hope to help him figure out how to help Suzume.

Sanzo uses Yutaka as a demonstration for Akane to understand the value of talking about your feelings. When Yutaka is finally honest about her past struggles and how they’ve affected her, it helps Akane realize what he needs to do, and it allows Yutaka to die happy.

I can imagine someone criticizing this character arc’s resolution as too simple or too reliant on tropes. The quirky, supernatural Yutaka swoops in to save Akane’s relationships. Or Akane saves the damsel in distress, freeing her from the burden of a lifetime of mental health struggles just by being a good guy. But aside from those arguments (which ignore the nuance that Sanzo fills his characters with), the fact that either one is a remotely defensible position is, to me, a testament to Sanzo’s skill as a character writer. The ability to create something so thematically rich and open to interpretation will always impress me.

Suzume

Suzume’s caterpillar form is a representation of what can happen when the pressure for women to be some sort of avatar of ideal beauty and deference becomes too great. Akane learns from Yutaka that Suzume had actually made quite a few wishes at her shrine prior to the caterpillar one. All of them were for Akane’s benefit – mostly things like “I want to be better at cooking” or “I wish I was cute.” Of course, Sanzo’s implication is that she’s good as she is, but she’s been conditioned to think it’s never enough.

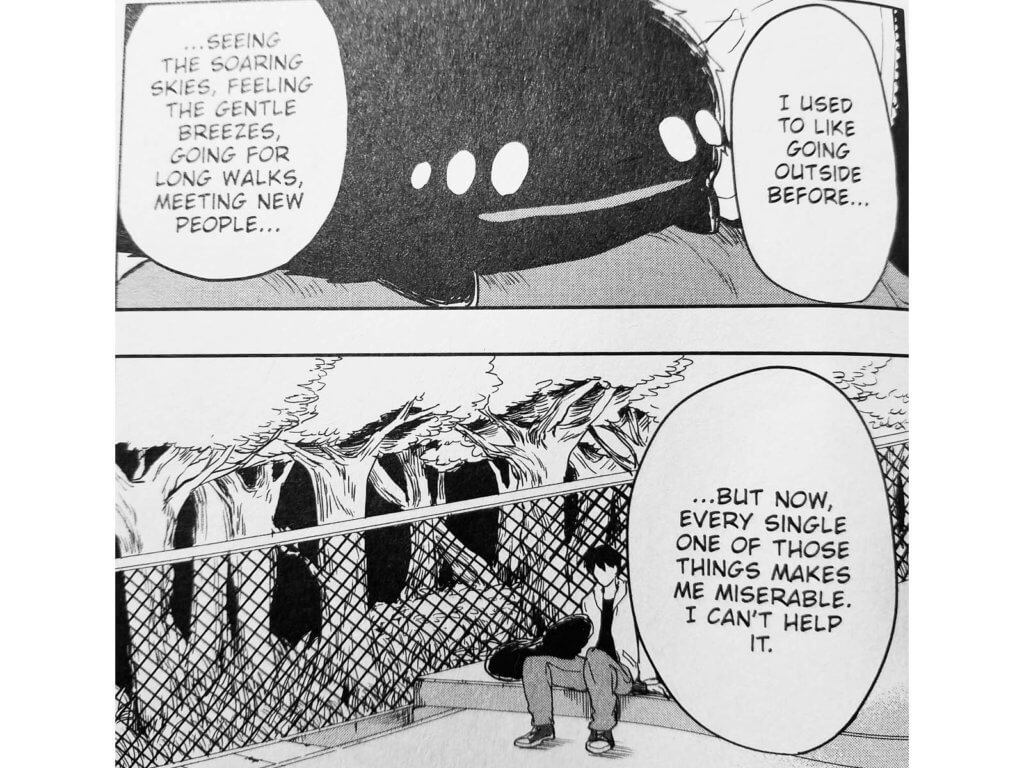

So when Akane, the one person who should love her no matter what, rejects her for being too perfect, it’s the last straw, and she makes the caterpillar wish. Her stumpy insect legs make it incredibly hard for her to do the simplest things, like bathe or even move around. Human food begins to taste disgusting to her, and she has to force herself to eat, then eventually stops eating at all. The longer she stays in her caterpillar form, the less she seems like her old self. These are clearly metaphors for depression and eating disorders, two oft-cited byproducts of impossible beauty standards for young women. And while they’re ham-handed as hell, they are pretty effective.

Where I think Sanzo slips up a bit is that they try to make the caterpillar metaphor pull double duty, as both the product of Suzume’s suffering under an oppressive system, and as a conscious attempt to remove herself from that system. Suzume chose to become a caterpillar, but nobody chooses to become depressed or develop an eating disorder.

Maybe Sanzo sees it as Suzume trying and failing to dodge the damage of society’s expectations, and then succumbing to its effects, almost like an unsuccessful suicide attempt. I think that oversimplifies the mental health impact of the patriarchal system Sanzo is criticizing, though, which is a risk you take when you use a super simple framework like Caterpillar Girl does. Either way, Suzume’s arc as a metaphor doesn’t work as well for me as Akane’s or Yutaka’s.

The End

Purely as a dramatic arc, however, it works great, as does Akane’s. All the more so because there’s no contrived storybook ending. Wrapping up a romance as tangled as this one with a nice little bow and an easy solution would feel false.

Near the end of the book, Akane uses a talisman left to him by Yutaka to turn Suzume back into a human. But she still can’t eat, and she’s not the bright and happy person she used to be. She bails on social situations, and she still harbors some resentment for Akane, even after he’s finally admitted his love for her. The damage done can’t be healed just like that.

Then Suzume alters the talisman so that instead of transforming her into a human, it turns her into “what I want to be most right now.” To her surprise, she still looks human. Akane appears and tells her, “until you never have to second guess my love for you, I’ll be here by your side.”

This is the closest the two will get to a happily ever after. Akane is committed to reversing the damage he’s caused, but he knows it won’t be easy. Suzume has accepted that she can’t return to the status quo, but that isn’t what she wants anymore anyway – the status quo wasn’t good enough in the first place. What I think Sanzo is trying to tease out of this strange little fable is that while there are steps women can take to minimize the harm the unreasonable expectations of a patriarchal society have on them personally, they shouldn’t have to. Men should be working to solve the larger systemic issues that they created.

Caterpillar Girl and Bad Texter Boy achieves a depth of characterization and a sensitivity that shonen romance manga rarely do, especially over such a short page count. Your mileage may vary, but I was consistently amazed, and I can’t recommend this book enough.

You can read more about “Caterpillar Girl and Bad Texter Boy” on Anime-Planet, and order it on Amazon or RightStuf.

Special thank you to Yen Press for giving us the opportunity to review this manga.

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page