Some may not remember the Walt Disney Feature Animation Florida studio, which churned out hits like Mulan and Lilo and Stitch, though those titles are still well beloved today. The studio was shut down in 2004, effectively ending any projects that the employees had been working on or transferring them to other divisions within the company. All except one, that is.

Andrew Simmons worked at the Disney Florida studio from its conception to its finale and is known for his work on popular titles such as Mulan, Lilo and Stitch, Hercules, and The Little Mermaid. During his time working for Disney, an idea for a short came to him about the journey of a flower, floating down a river in 15th century Japan. His love of Japanese art and visuals spurred him on to create something combining Disney’s animation techniques with Japanese woodblock paintings, and work started in 1998 on a film titled The Flower to do just that. However, with the studio closing its doors a few years later, the future for the film didn’t look great. But as luck would have it, Andrew was given special permission to keep all of the assets that had been created for The Flower so that he may finish it himself.

Now, 25 years later, The Flower is close to completion.

I was given the opportunity to sit down with Andrew Simmons and Nicholas Zabaly, the Director and Producer of the short film respectively, to discuss its journey as the last legacy of a forgotten studio.

Kaley: What was the inspiration for The Flower?

Andrew: Watching Akira Kurosawa’s Ran when I was eighteen in the theater–that probably made the biggest impression on me than just about anything. And then merging that with my love for Japanese animation and growing up on Robotech and Star Blazers and all the things that were cool that Disney would never tell. I remember working at Disney and trying to tell people [about these things]–it’s funny how insular a lot of people at the studio were, and how they were not familiar with animation from around the world.

Nicholas: Fairly early in Andrew’s time at Disney, Andrew and a number of other animators and artists got together to watch Akira not long after it had been made, and that was a very important moment and experience. The early Ghibli films were inspirations. The Japanese woodblock print masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige were major inspirations.

The state of Florida had a great program with the Disney studio with what was essentially a reference library that Disney artists and staff could pull from. They could get any book they wanted, and it would be supplied. Andrew and the crew made very good use of that to be able to obtain reference books on Japanese art and history, and anything that could help. So a huge amount of work and research went into this.

Andrew: That was the days before the internet, when you had to actually get a book and check it out from the library and read it. Or you had to borrow your friend’s buddy’s copy of a movie from Japan that you had never heard of, which is actually how I watched The Ring the first time.

Kaley: I know you’ve been working on this project for over 20 years. How does it feel to be this close to seeing it completed?

Andrew: Amazing and humbling. It’s amazing to see the work that everyone produces. When you see someone work and bring their skill to your project–that’s humbling. And knowing the level of quality we’re receiving back from people, it’s just amazing. It’s like, I could never do this. When you’re leading a project, regardless of what that project is, a good team leader puts people in place that can bring the best to the table. We’ve been very, very blessed to have people come onto the project that were previously at Disney, and [people who joined later], who have brought their A game. And the film looks fantastic for it.

Kaley: We’ve talked a little about how diverse the team working on The Flower is. Can you talk about how having such a diverse group working on this has affected the film?

Andrew: Well, the great thing about having a diverse team is it brings a wide variety of viewpoints, and people looking at things differently, looking at life differently, having different life experiences. We have people working on four continents–China, Japan, Brazil, and Ukraine–just all over the map. And bringing their different approaches has widened the breadth of the project. You can do a project on your own, be very focused and get your vision, but when people add their visions to it, it raises the whole project up a level.

Nicholas: On our Indiegogo, we’ve done profiles on some of our artists, and I was helping Natalia Skryabina, who’s an animator from Ukraine, with her profile. She was telling me through email about what animating The Flower at that particular part of the film felt to her in her immediate experience. A little more than a year ago, she was living an ordinary peaceful life in Ukraine, and suddenly had to leave her country because of everything that was going on, then subsequently come back and is now living and working in a literal warzone. Without getting into spoilers about the movie, she is animating a point where, if the flower is a living thing or a character, it has been dealt a severe blow–a trauma–and yet is somehow carrying on. I think the connection between that emotion in the line that she is producing and her own emotion of living through her experience in this moment is a direct connection. Each person who has worked on the film has brought their experience and their emotion into the line that they draw with. And since our film has no lines of dialogue, only lines of art, you have to be able to speak through those.

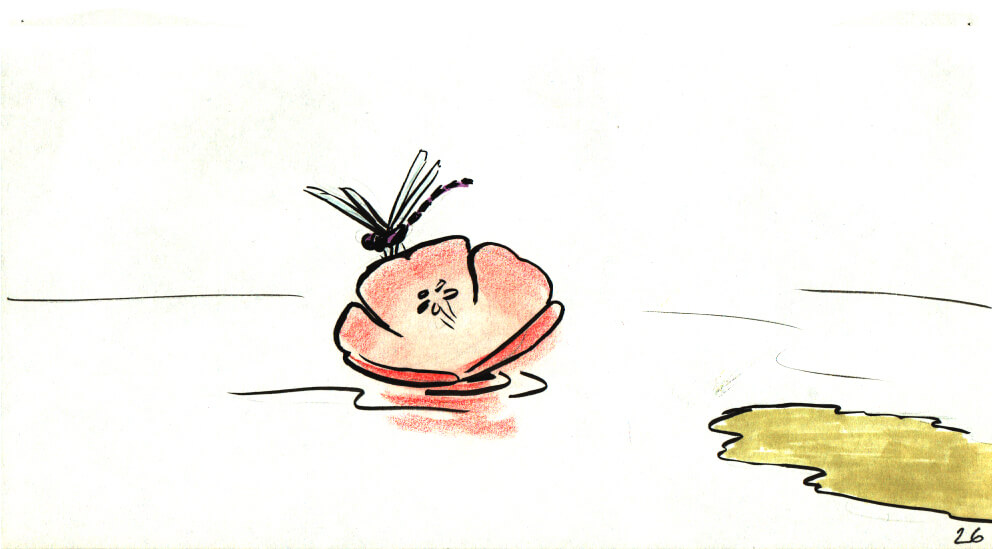

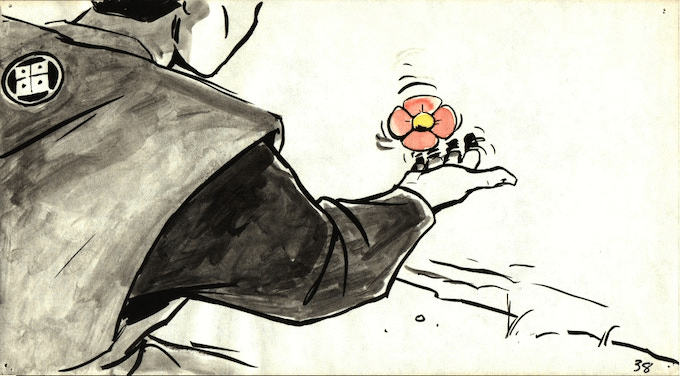

Rough Animation by Ronnie Williford

In-Between and Clean-Up Animation by Simin Huang

Animation Inked by Andrew Simmons

Animation Painted by Wenrui Huang

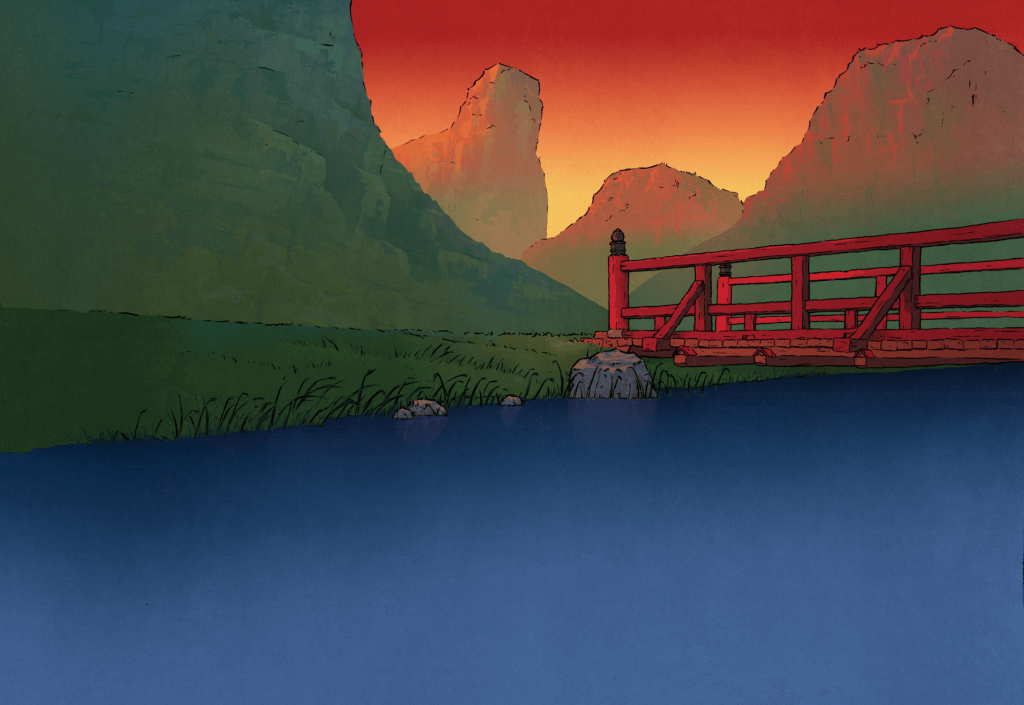

Clean-Up Layout and Background Painted by Jaison Wilson

Kaley: What has it been like to work with these talents around the world rather than only people who can commute to a local office?

Andrew: Lack of sleep. (Laughing) The biggest thing that Nicholas and I did, knowing that people are limited by language barriers and by time availability, is try to make ourselves as available as possible. If we had to do Zoom [meetings] at midnight, we were doing Zooms at midnight. It’s whatever fits the artist’s schedule. It’s my project, so I need to be the one that makes myself accessible to them, however that morphs and looks. What we found is that it was best for us to be incredibly detailed in our emails. When we would send a scene out, I would literally write up everything I wanted, all the action I wanted, where the characters are looking and why the characters are doing what they’re doing–just lay out everything. Then I’d send it to Nicholas, [who has] been incredibly gracious with his time, [and he’d take] that email and literally [take] it to the next level like a college dissertation so there’s nothing left to chance. And most people have been very, very willing to follow the notes that we provide, so there really hasn’t been any problems. Everyone has a clear understanding of what we’re looking for. Most people come to the project because they love the project. I had one person come to me and say he wanted to join because he wanted to animate a samurai and said, “I’ll never have another chance to animate a samurai in my life.”

Nicholas: As Andrew said, we would provide detailed notes. We would detail the motivation of the character in the moment–this is what they’re thinking, this is what they’re feeling. Somehow the line [work] needs to express this. And people would do it! That’s the thing that’s really amazing. I’m not someone who can draw myself. Being able to see words that Andrew and I typed into an email converted into a performance in drawings is basically a miracle.

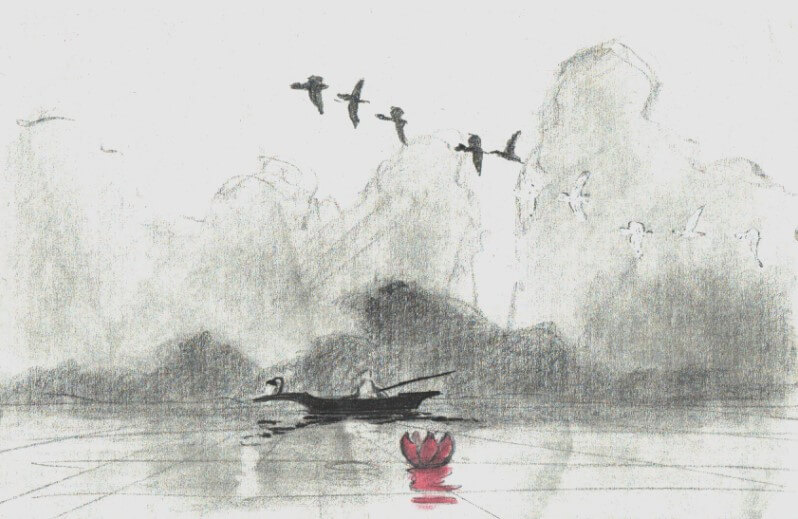

Rough Refinement Animation by Nelson Cabrera Curbello

In-Between and Clean-Up Animation by Emmanuel Codilla

Animation Inked by Andrew Simmons

Animation Painted by Wenrui Huang

Background Painted by Jaison Wilson

Kaley: What was the inspiration behind merging Disney’s animation style with Japanese woodblock print, and how does that support the story of The Flower?

Andrew: I’ve always had a passion for art, even though I didn’t go to art school. It’s kind of funny, I actually dropped out of college to take the job at Disney. So, I didn’t have traditional art training, and what I learned of art I researched on my own. Having the attraction to Japanese culture, being able to research different artforms, and get involved with woodblock prints and how they were made–I just thought it would be really, really cool. Wouldn’t it be neat to see them come to life? So that was the original intention–to bring a woodblock print to life. But it did morph over the years. A couple years ago, we were still real close to woodblock print colors because everything was grayer, real dark, kind of a desaturated look if you would. [While] it looked fantastic, it just didn’t fall into my goal to have something as visual poetry. We really wanted the colors to pop. We wanted the colors to be strong, clear, not muddy. So there’s very little brown in the entire film. There’s mostly gray, blue, and some red. But even with the red, we were very careful to stay away from the brown [shades] so that it was clear. [By] pushing that color back into the short, that is what brought it back to the Disney aesthetic.

Nicholas: When people think of the more muted colors of woodblock prints, an important thing to remember is that we’re often looking at multiple generations removed versions of the [originals]. It’s like the number of times you play a record, it gradually degrades. Well, the number of times you make a woodblock print from the block, it becomes less intense. The lines are not as clear and the colors are not as vibrant. If you’re able to look at first generation woodblock prints, which are exceptionally rare but I have seen some when I’ve been to Japan, they look more vibrant like what we’re doing.

Kaley: What have been the differences between working on the film at Disney versus working on it as an independent group?

Andrew: Well, when we were doing the film at Disney, we were using Disney’s equipment on Disney’s time because we worked on it during down time between different films. We were an attraction at Florida, so we had to be in the fishbowl so people could come through and see us working. And the great thing is when people would tap on the glass and ask if they could see what we were working on and then we’d tell them, “No.” But to have unlimited resources… Anytime you have unlimited resources you can reach for the stars, and that’s one of the reasons we made the decision to [animate] the film on ones. Again, we’re going for visual poetry. We want it to look Japanese. We want it to be visually stunning. And we want it to flow. It has to have a sense of flow. It’s like trying to write a haiku with visuals. It’s got to have a unique sense of flow to it. At Disney, we would traditionally [animate] on twos, and when you get a camera pan, you’d usually get some stuttering. To alleviate that, we did it all on ones. We wanted to keep the scenes very fluid and I didn’t want the camera to be stuttering at all.

Nicholas: A lot of people reading this may not know, but the Florida studio was a theme park attraction within the Disney World complex. So if you went to Disney World from the 90’s to the early 2000’s, you could literally walk by a glass window and peer in and watch the animators animating Mulan and Stitch, or Brother Bear and whatever else they may have been working on at the time. Andrew was there on the other side of the glass for portions of his career. You were kind of on display, but you were also directly telling people what it meant to be working at Disney. I’m sure millions of people experienced that attraction and I’m sure there are a lot of people out there today that specifically wanted to become 2D animators because they saw something like that when they were a child.

But to elaborate [animating] on ones, basically what that means is every single frame of the 24 frames per second is a unique drawing. And that’s very unusual. Disney didn’t animate that way. They would double expose frames so it would be on twos. Your typical Japanese anime might be between twos and fours. Sometimes even fewer, and that’s what produces that very interesting sense of timing and movement by varying the frame rate within a shot. But to animate on ones is very, very time consuming, challenging, [and] costly. You have to pay very close attention that it remains consistent frame-to-frame. That’s why it’s virtually not done. If you watch Who Framed Roger Rabbit from the late 80’s, that’s the last major project that was animated on ones, and it’s because it was merged with live action. So it’s almost unheard of, honestly.

To do a movie in a Japanese woodblock print style on ones with a varying final line that tapers between thick and thin points in the same brushstroke… Andrew, you packed so many challenges into this for us! (Laughing) But somehow we found people who are capable of doing it, which is pretty amazing.

Andrew: That’s one of the great things about the technical advances, because I remember presenting the idea of the brush stroke and animating the brush stroke on the line and giving it the ability to breathe, and all of our cleanup artists, they use mechanical pencils with the thinnest lines possible. And they’re like, “No, we can’t do that.” And I was like, “Well, can you use a regular pencil?” and they were like, “No.” So that’s one of the great things where, coming into the digital age, I’m able to translate my vision, my goal. I want to see the lines taper. I want to see them smooth. I want the edges to look like a brush stroke. And we’ve had some amazing cleanup done by our cleanup artists in the Philippines. And I’m just like, “Wow. That looks ten times better than I thought it would.”

Kaley: How much has the story changed from its original conception in 1998 to today?

Andrew: Very little. The story has actually maintained its consistency around a flower that falls into a river and what happens to it. There were a few scenes that were cut. We did try to explore a couple of different ideas, but again, with the film going for the goal of visual poetry and trying to keep the film always moving, some of the ideas–even though they were good–would bog the film down. So the original, core idea probably stayed 90-95% straight through from the time it was storyboarded by Tim Hodge.

Kaley: What has been the most challenging aspect for this project so far?

Andrew: The most challenging aspect so far was actually just picking it up and doing it. It’s always easier to not do something than it is to do something, and that sense of not wanting to fail at it. You want to pick up your project and you don’t want to disappoint the people that are working on it. I didn’t want to pick it back up again and have people work on it and have it drop off the map again because I would feel like I’m disappointing those people. I didn’t want to pick it back up again and have it not look the best that it could. I wanted it to be the best looking film that I could produce. If it was less than that, then I’d feel that I missed the mark and let down the people who have worked on it. So the weight was heavy. But you know, you get good people around you and people that encourage you. And that’s the hardest thing about anything is picking it up and starting, regardless of what your project is. But once you get that ball rolling, you just keep at it. And when you hit an obstacle, take a day break, go for a walk, relax a little bit, then come back to it. When you get a fresh perspective, you can overcome just about everything. And we’ve overcome a lot of stuff.

Nicholas: From my perspective, the hardest thing was stepping into a project that had already been going for so long and not wanting to let people down, including all the people who had worked on it in the past who aren’t working on it anymore because the closure of the studio was a traumatic experience for a lot of people. A lot of people have not wanted to go back and revisit it for that reason. I have thought for a long time that the completion of this film is the last piece of their legacy that’s still out there left unfinished, that’s likely to ever be finished, and could maybe provide a little bit of closure. Approaching and thinking about that is intimidating. You want to do well by the people who did that work, and you also want to do well by the people who are contributing right now who may never have another chance to do something else like this. You want it to be a good experience. You want this medium to live. And so, finding ways to navigate all of those doubts is by far the most challenging thing. But then seeing how people step up and deliver to create the miracle is also the most inspirational thing that makes you feel like you can get through whatever it is.

Clean-Up Layout and Painted by Jaison Wilson

Kaley: As veterans of 2D animation studios, why do you think preserving hand drawn animation is important?

Andrew: I think preserving it is important like with anything. Traditions can be a good thing. I’ve actually started following an account on Twitter, and the account highlights sculptures from 15th, 16th, 17th century and I was totally blown away by a piece that had a net over somebody’s leg. And when you think of it, this is a block of marble that someone sculpted out of, and they were able to make it look like a net. It’s crazy. I couldn’t do that. I don’t know anyone today that could do that. It’s a little sad when you think [about] how that skill, that mastery, is lost. I think that’s the same approach with 2D animation. People like Mark Henn–

Nicholas: The Bancrofts, Glenn Keane, just so many people.

Andrew: –when they’re gone, if we’re not making 2D traditional films, even digitally, that mastery and knowledge is going to be lost with them. And that’s tragic.

Nicholas: It’s not just that it’s a collection of people, it’s also the institution itself. Because individual people can raise themselves up to a certain level of skill, but when you combine all those people together in a studio you have the advantage that, somehow, everyone is able to go further than they thought they’d be able to because they were together. And the loss of the hand drawn tradition in the United States caused all of those people who were at the peak of their powers to be cut off at the prime of their creative lives. And if you lose that, if it falls too far into the past, it becomes like [the sculptures Andrew mentioned]. You can’t then so easily replicate [the works]. It’s not that you’ve completely lost the ability altogether, but it becomes that much harder to get back to where you were, much less to get better than where you were. The idea of being able to maintain, or reach and maintain golden ages in the animated medium is important, and it’s a choice that people make. If you let it go, you won’t have it anymore, you won’t be able to take advantage of it anymore. So for us, it’s not that there is this existential struggle. It’s much simpler than that. If you value something, try to keep it. There are a lot of people in the world looking at our film who value it and want to keep it if they’re only given the opportunity to do so. It’s important to give those people the opportunity to do what they’re passionate about. And it’s important to give people in the world the opportunity to experience what they’re passionate about. That’s why it’s important to maintain this.

Kaley: With the current climate around artists and the rise of AI art, what do you think the future of hand drawn art looks like?

Andrew: I don’t know if I can predict the future. Technology is changing so rapidly that it’s hard to predict what the animation industry will look like in five to ten years. Or will there even be an animation industry? It’s interesting that I have some friends, and I’ll look at their LinkedIn and Facebook, and some of them are embracing the change and some are resistant. It’s really hard to see where it’s all going to shake out. I do think though, like Nicholas said, there’s a core of people [who love the 2d animation medium]. You’re always going to love a medium, and that’s what 2D animation is. It’s a traditional medium way to tell a story. I don’t hold any ill will towards 3D animation or anything like that, they’re all just mediums. What’s best for your story, that’s what’s more important.

In Japan, [what’s] really interesting [is that] animation is readily accepted in all story formats, whereas here in the States it’s, “Oh, that’s for kids.” No, it’s not. It’s just a format for telling a story. It all depends on your story and how you really want to tell it.

Kaley: Is there anything in particular you’d like people to know about your project, or any words you want to make sure are conveyed?

Andrew: If I have any words of encouragement, I would hope that it would encourage someone to do their own independent work, regardless of what that work may be. Tell something. Create something. Create art. Create life. Take from your life experiences and create anything. That act of creating–you put yourself in that project, whatever that project may be.

My kids have been with this project for years and years. So if I want to tell my kids anything, it’s to finish what you started. Pick it up and do it. Do something, create something. And hopefully the world will be better for it.

Nicholas: I would second that. If there’s one thing I hope that people will absorb from this is to feel inspired to go and create and to keep these important institutions and mediums alive. [They] can only go on if people care enough to make it go on, to put the time into it and do it. I think that the world is a less rich place if we don’t have all of these artistic expressions. Art is what makes life worth living. And if you want to have that in your life, you have to go out and do it, support it, and value it. I hope that people feel inspired by looking at this film and the journey this film has gone [through] to do those things in their lives.

During our talk, Andrew and Nicholas told me that they are hopeful they can have the film ready by early 2024. Their plan is to submit it to film festivals around the world, particularly in countries where their artists and animators live, and to aim for a digital release sometime after that.

The project still has a few hurdles to get through, though. The team currently has an Indiegogo campaign running that will help them finish the project, and the campaign ends September 16th. To find out more about The Flower, you can check out their website for updates, videos, pictures, and more.

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page