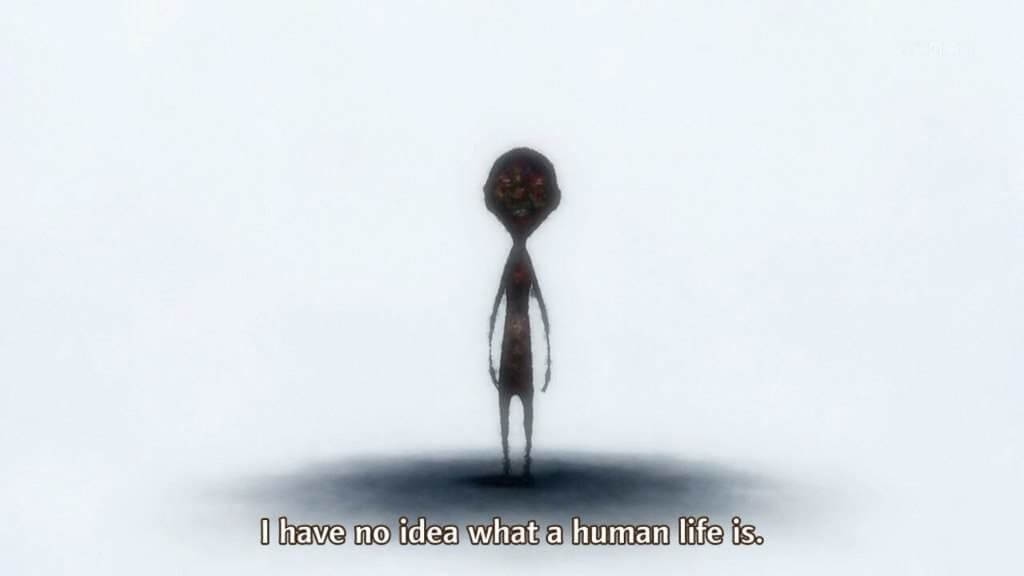

Ningen Shikkaku, often translated as “No Longer Human” in English, has the literal meaning of “disqualified (from being) human”. Currently, the second most popular novel in Japan, Osamu Dazai’s final work continues to be read, discussed, and studied in the country. Though the novel has received favorable reviews from critics in the West, it’s never enjoyed the popularity that it did in Japan.

Indeed, this could be due to the novel’s central theme; alienation from a society bound by strict traditions and customs. A society which values appearance and reputation much more than in the West. And yet Ningen Shikkaku also possesses a quality unique among Japanese novels. It is more akin to the likes of Western writers such as Dostoevsky or Kafka, in its portrayal of the universality of suffering and alienation it presents, regardless of the causes or setting it is presented in.

Suffering caused by loss

Ningen Shikkaku is a dark, depressing narrative which charts three different stages of Oba Yozo’s life, based on three photographs introduced in the prologue. The first is of him as a child whose fabricated smile and cheerfulness evoke “unspeakable horror”. It’s clear that Yozo suffers from an extreme case of anxiety, unable to disagree with anything or argue back against anyone, and fearing all and any human interaction. This leads him to develop the personality of a “clown”, an inauthentic version of himself which he abuses to make himself appear more likable. This constant act of deception is a great source of sorrow for Yozo. And yet, there are instances where he is truly able to express himself: “The pictures I drew were so heart-rending as to stupefy even myself. Here was the true self I had so desperately hidden.”

Yozo discovering his “true self” in a painting is similar to that of Wilde’s Dorian Gray, albeit with distinct differences. Where Wilde’s protagonist is ultimately led into a spiral of debauchery, drugs, and alcohol abuse due to discovering his true nature within the painting, Yozo’s drive to do so is arguably partly due to him losing these paintings of himself. In doing so, he lost a part of himself – a fragment he desperately and unknowingly seeks to rediscover through all of his human interactions throughout the story.

Yozo becomes acquainted with many people throughout the novel in an unspoken hope to make a genuine connection with any of them, and yet all of them seem to only further his suffering. Tsuneko is one such character who for a fleeting instant brings a source of joy and comfort to Yozo; the night he spends with her is one of “liberation and happiness”. His decision to commit suicide with her shows the extent of Yozo’s commitment (“of all the people I had ever known, that miserable Tsuneko was the only one I loved”) to her. One of the most tragic and poignant sections of the novel is simply this admission, a glimmer of raw emotion and affection otherwise entirely missing from the work. However, Yozo survives the suicide where Tsuneko does not.

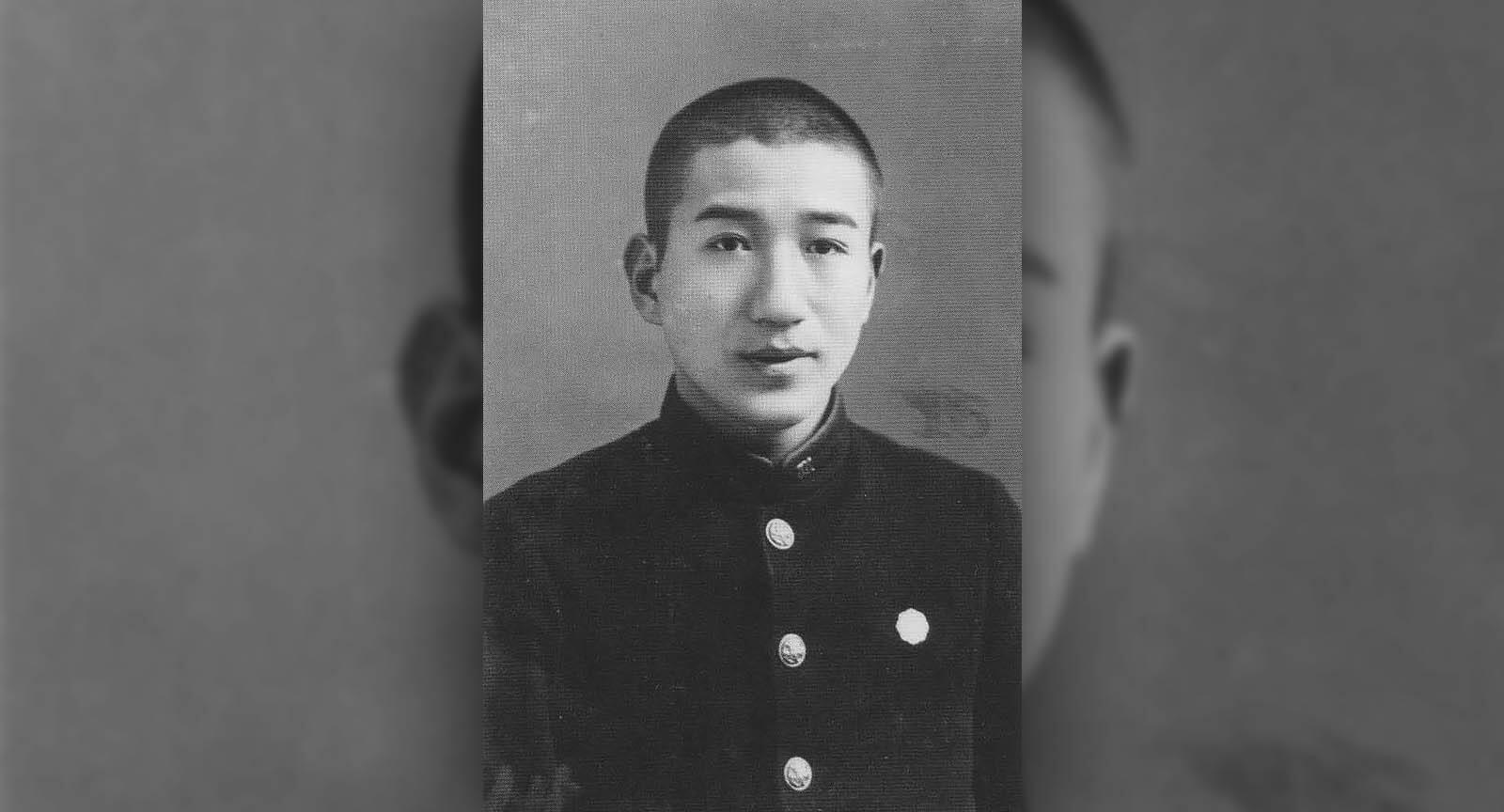

Tsuneko and the failed double suicide was inspired by Dazai’s own life, where he ran away with his lover, Shimeko Tanabe, and attempted a double suicide. While Tanabe died, Dazai was rescued by a fishing boat. In many ways, just like Yozo’s paintings, this novel was Osamu Dazai’s attempt at expressing his innermost emotions and experiences. The novel is structured in the first person “I-narrative” style which was often used as a confessional, personal, and direct style of writing by Japanese writers before and after Dazai.

Many events from the novel such as Yozo’s morphine and alcohol addictions were taken directly from Dazai’s own life. The simplistic and honest prose style of the novel helps narrate the story in a seemingly unbiased and authentic way, contrary to Yozo and perhaps Dazai’s own experiences with communicating with people around them. Extended metaphors, fanciful rhetoric, and poetic prose are very sparse, methods which impregnate the entire narrative with a miserable, and at times agonizing, sense of bleakness – accurately communicating Dazai’s outlook of life.

Salvation within suffering

Ningen Shikkaku is not at all a happy story, and yet paradoxically it remains one infused with hope to its core. In the third part of the novel, the narrator questions the root of his suffering. One of the earliest conclusions he arrives is that it is society’s fault. However, Yozo soon stumbles upon the revelation: “what is society, but an individual”. This revelation parallels the views of European writer Franz Kafka.

In his novel The Trial, a priest declares that the complex, labyrinthine trial Josef K. is forced to undergo (a great source of suffering) is one of his own doing – he is able to “enter and leave” the trial as he pleases. The blame for Yozo’s suffering is similarly his own – “my unhappiness stemmed entirely from my own vices.” Though this revelation is of little matter to Yozo, it remains ingrained as one of the most important messages of the novel – true freedom is finding happiness and making one’s own choices in spite of what one is forced to undergo.

Another brief glimpse of hope is when Yozo sees an old woman, a complete stranger, look at him with “tears brimming from her big eyes” and feels a powerful sympathy for her. The suffering she has undergone has made her, unlike anyone else in the story, truly understand Yozo.

The ending of Ningen Shikkaku is also one of hope. In a singular, striking sentence, the only objective character in the entire novel describes Yozo as “an angel”. Unlike Wilde’s Dorian Gray who cannot see the extent of his own cruelty, Yozo is a character who in his supposedly objective narrative, failed to see his own gentler side, his capacity to love, and his tenderness.

While Yozo may repeatedly consider himself to be disqualified from being human, he is actually the striking example of humanity – cruel, callous, thoughtless, and yet possessing a tender, kind side unknown even to himself. Where most writers delight in showing the hideous and hopeless nature of humanity alone, Osamu Dazai in his masterful subtlety portrays the unsightliness of mankind always with a genuine and honest redemption, untouched by exaggeration or sentimentality.

Ningen Shikkaku’s Legacy

Dazai committed suicide very shortly after the publication of Ningen Shikkaku. In many ways, it is his last will and testament. Equally, it is his salvation, perhaps a redemption that so many people of the future would be able to identify so strongly with Dazai as a writer when no one could understand him in his own lifetime.

Today, the legacy and impact of this novel are apparent in Japanese culture, from literature to animation, film, and manga. It has received three separate manga adaptations, an anime adaptation in the Aoi Bungaku Series (a series which adapts modern classics of Japanese literature) as well as the live-action movie The Fallen Angel. The narrative style of Ningen Shikkaku has also influenced contemporary writers and manga artists such as Nisio Isin who, also adopted a narrator who is unable to see his own positives in his bleak attitude of himself and his life in the novel series Zaregoto. Inio Asano as well charts a similar narrative with themes of the loss of innocence and youth in Oyasumi PunPun.

It may not be surprising that adolescents and adults alike in Japan, a country with one of the highest suicide rates in the world (possibly due to the high-stress school and work environments), would come to relate so strongly with this novel. Yet, it is more than just a story of alienation and suffering – Ningen Shikkaku is a novel about humanity itself that is able to be understood and appreciated, no matter what part of the world the reader may live in.

Citations

http://www.planetpublish.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/The_Picture_of_Dorian_Gray_NT.pdf

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.148752

https://www.planetebook.com/ebooks/The-Trial.pdf

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page