There are as many kinds of isekai stories as there are stars in the sky. Is the protagonist a hero, a spider or a villain (or villainess?) Were they summoned or reincarnated? Are they weak or overpowered? Do they want to save the world, revenge themselves on others, or find happiness or prosperity? It’s easy to assume with all this variety that the possibility space has been exhausted.

Then came the 2024 visual novel Seedsow Lullaby. Penned by the famed doujin scriptwriter Kazuki from STUDIO・HOMMAGE, the game is something that I have never seen before: an intergenerational family isekai story. Its protagonist, Misuzu, travels with her mother Yoko and future daughter Tsumugi to the Eternal Realm where the gods dwell. There they must serve their duty as Maidens and ensure the gods pass on, so that their lands will be reborn after the fall of True Winter.

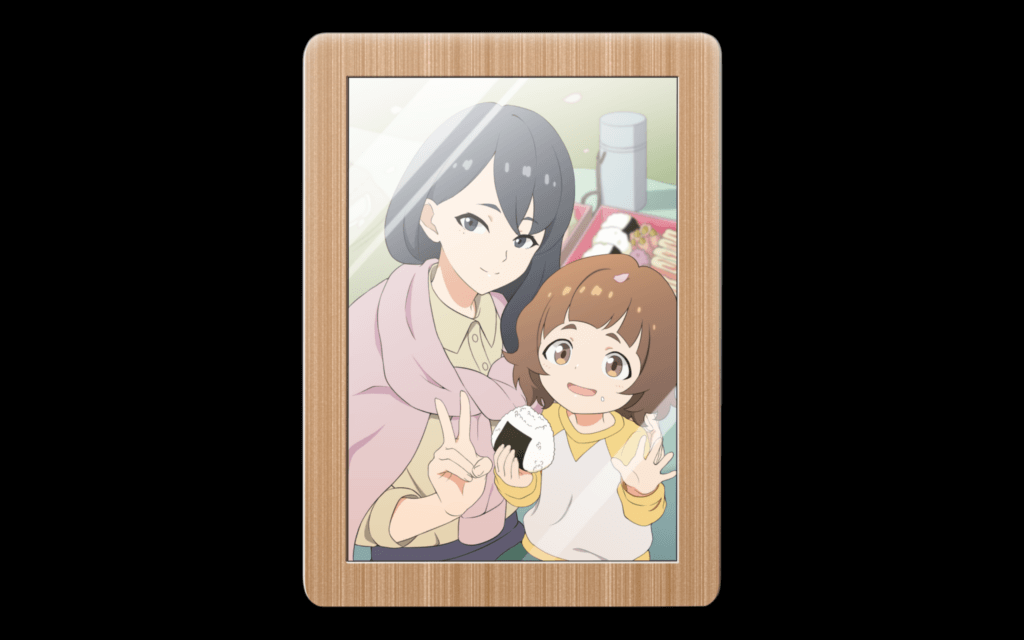

Yoko died not long after she gave birth to Misuzu; Tsumugi will not be born for decades. Yet here they all are, alive and sixteen years old, crossing worlds as heralds of the Seedsow. Behind walks their guide, Hiruko, who has lived among the gods for his whole life.

Hiruko claims that he is Misuzu’s younger brother who was never born. Should they convince the gods to play their roles, he says, his own long-held wish will be granted. But there are no such rewards for Misuzu, Yoko or Tsumugi. All they have to gain is time spent together in pursuit of their task. A time that is their one and only miracle.

The same age and time

Just as other isekai stories present fantasies of becoming the strongest, being adored or taking revenge, Seedsow Lullaby presents meeting your mother or granddaughter as a wonder in itself. Yoko died when Misuzu was a child and before Tsumugi was even born. Misuzu only ever knew her mother through hospital visits. Tsumugi loves Misuzu but only as her mother. Now all three have the opportunity to meet at the same age and the same time.

Yoko can spend time with her daughter and argue with her granddaughter. Misuzu has the chance to learn who her mother was unburdened by illness. Not just that; since Misuzu’s father has worked abroad for much of her life, her time with Yoko is the first in years that she has received undivided attention from a parent. Meanwhile, lonely Hiruko relishes the company of humans as opposed to ever-changing gods. The four of them form close bonds despite the decades between them.

Seedsow ritual

That’s not to say that everything goes smoothly. Yoko was born many years earlier and is much more old-fashioned in her values than Tsumugi. Misuzu is stuck mediating for the two of them. Then there is the ritual of Seedsow itself. These three girls must kill and cook animals for supper, escape ferocious creatures and even climb mountains so that the gods may die. Tasks that would be a challenge for anybody, much less sixteen-year-olds.

As time passes and True Winter approaches, Seedsow Lullaby asks whether the notion of family can hurt others as much as it provides comfort. Yoko struggled against sickness to be healthy for her parents and then for her child. Tsumugi was scarred as a kid by the trauma of her father’s abusive family abducting her from school. Misuzu longs to be embraced by Yoko, and yet is terrified by how Tsumugi compels her to sacrifice herself for somebody she hasn’t even given birth to yet.

The violence of a child

Families are systems of ritualized violence. Not just the violence of a mother or father hurting their child. But (as Misuzu reflects) the violence of a child inflicting themselves on their parent. At that moment, the parent is overwritten; they transform from an independent human being into something else without their say. Then again, a child doesn’t have a say in being born, either. Each wounds the other simply by fulfilling their role in this cycle.

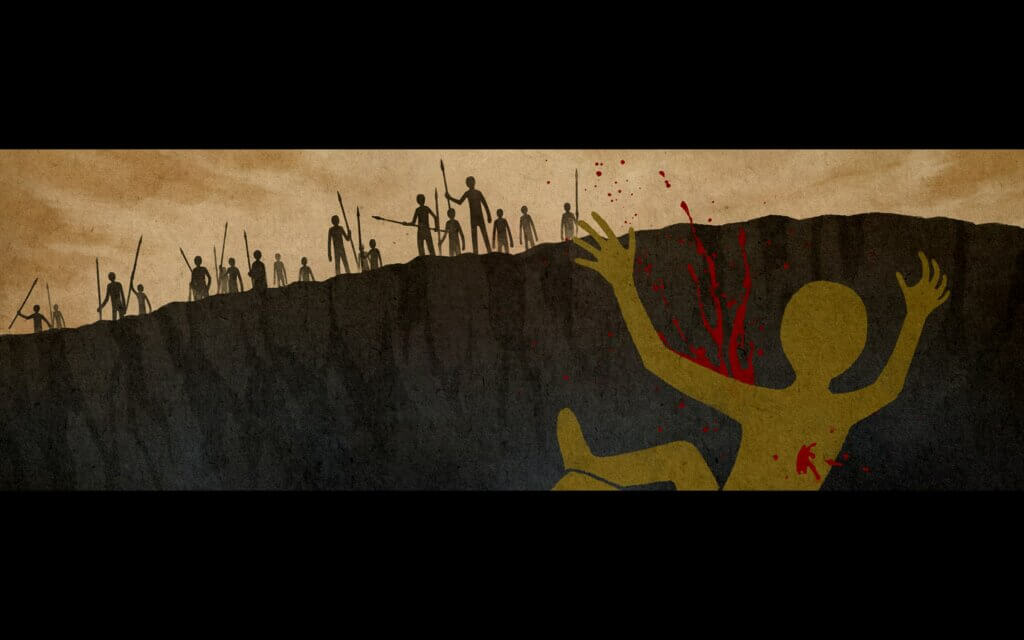

The world of the Seedsow reflects this as well. Its gods must die so that their lands will be reborn after True Winter. Should they forsake their task, their children are condemned to suffering and death for generations. Each land has its season: Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter. They each respond to the end that is True Winter in their own way.

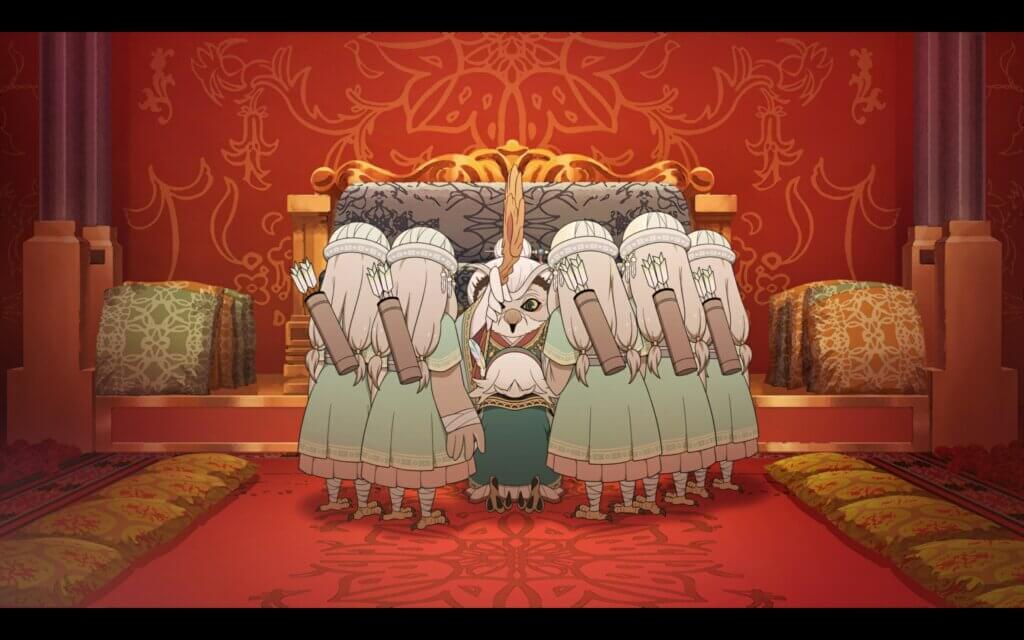

The god of Fall accepts his death with grace, as his predecessors resisted the Seedsow and paid for it. He hopes that his body will grant the children of his children a happier life than his. The god of Spring finds every means to postpone his death. Who will care for his two daughters if not him? But he sacrifices himself in the end so that they might one day have a future.

There is no Seedsow ceremony in Winter, for it is too cold for the gods. The land is haunted by the hungry and the forgotten.

Narcissistic parents

Summer is worse. Generations of prosperity have ensured the happiness of its people. Yet all are convinced that they have grown beyond the need for Seedsow. They tie their gods up with rope like chickens and lock them deep underground where nobody can find them. Lost in the heat of Summer, they no longer recognize that True Winter’s cold will knock down their towers and obliterate the achievements of their ancestors.

The people of Summer are led by a Matriarch. They insist that the Matriarch knows best, and that even if she doesn’t, it’s better to believe that she does in a world where faith determines power. In reality, though, the Matriarch is a narcissistic parent, no different from Tsumugi’s abusive grandmother. She considers her people not as individuals but as objects that she owns. Their success or failure reflects on her and so do their thoughts. Those who stand up to her, who assert their own personhood, are smothered.

Even when separated from the Matriarch, the children of Summer do not improve. They turn their knives on their neighbors and each other. They succumb to cults. Because their mother did not love them, they (with a few exceptions) never learned how to love others. The product of a family cycle that inverted itself to produce monsters.

Fathers and daughters

There’s a danger in that line of thinking, that family creates destiny. There are many people in the world after all who chose to reject blood ties for their own, chosen family. Yet I think that Seedsow Lullaby is right to point out that family is a powerful and even frightening thing. Too much love, a lack of love, the wrong kind of love, can change somebody’s life. Even if they reject it, define themselves against it, that love will live in their blind spot until they die.

There are also, of course, different kinds of parents just as there are different kinds of children. Misuzu’s father works abroad and can only speak to her remotely. Tsumugi’s father carries the weight of his cruel grandmother. The suffering that they experience cannot help but bleed into the lives of their kids. But it does not destroy them; the fathers and their daughters do what they can.

What you bring back with you

Misuzu herself is particularly interesting in that we see her at every step along the road from mother to child. Sometimes she runs to find Yoko and hold her tight. At other times, when she needs to, she hardens herself for the sake of her daughter Tsumugi. It doesn’t matter whether she is a child, a teenager, or an adult. As Seedsow Lullaby puts it, being a mother or a daughter is a state of mind. A role that you step into when someone needs you, or you need someone.

Learning these truths is part of the journey. That’s what sets Seedsow Lullaby aside from its isekai relatives. It’s not just concerned with the fantasy of traveling to another world, but with what the characters take back with them to their own. Memories of their mothers and grandmothers; what you lose or gain as you become a child or a parent; whether family is fated, arbitrary or somewhere in between. Misuzu, Yoko, and Tsumugi hold these lessons in their hearts even as the memories of their adventures fade.

Wish fulfillment

That’s what made older “portal fantasies,” like Fuyumi Ono’s Twelve Kingdoms novels, so memorable for me. Ono was uninterested in merely satisfying the reader’s hunger for wish-fulfillment. Her otherworld was a crucible to reforge her heroine from a lost soul into somebody able to stand on her own two feet. Seedsow Lullaby is just as invested in the self-actualization of its three mothers and daughters. The Seedsow ritual, and its cycle of children devouring the bodies of their parents (and, sometimes, parents smashing their children on the rocks for their own benefit) is a large-scale model of their own messy feelings.

But that, in itself, is wish fulfillment too. The game is just as much about the joy of traveling with people who matter to you as it is about learning. In no world would Yoko, Misuzu, and Tsumugi’s teenage selves ever actually meet each other. That’s the fantasy–not the chance to become the strongest, but instead an opportunity to spend time with loved ones before they disappear forever.

Seedsow Lullaby is available to purchase on Steam!

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page