Unparalleled by most of her peers in Japan, Liz & the Blue Bird director Naoko Yamada once again proves that she’s willing to go to lengths not many others in the industry are. Liz & the Blue Bird, a spin-off movie from the Hibike! Euphonium series, is right to not adopt the franchised name, because its approach to story is far different from the rest of the series and may catch viewers off guard.

Set not too long after the second season of the TV anime, the film follows Mizore and Nozomi in a bumbling relationship; the aftermath from the events of the second season. Their friendship is back in explicit status, but with it lingers a sense of ambivalence. Once again, with the awkwardness of both sides, their silence leads to another rift that threatens the status quo.

On the surface level, the story doesn’t sound too appealing; it arrives with the assumption that there won’t be enough new content for the narrative to explore. Story-wise, this generally becomes the case. We fall back into the same domestic territory for the two main protagonists, and the film doesn’t pay much attention to the rest of the cast (all of whom the audience is more familiar with). Kumiko Oumae, the protagonist for the rest of the franchise, isn’t around to help the two out again; in fact, she only gets a bare number of appearances and two spoken lines (both of which are background dialogue).

But from the very first scene, there’s confidence in Yamada’s direction. Extending a personalized style she consummated with Koe no Katachi (2016), she challenges herself to see how far her newfound style can go. She immediately traps the film on Mizore and Nozomi, deliberately neglecting many of the prior main characters and placing them on the sidelines. Their actions have little to no effect on the story Yamada wants the audience to focus on. In a way, she forcibly stuffs the viewer with just footage of Mizore and/or Nozomi. Even when the story feels like it should take a break from the two, it intentionally refuses to give the audience that luxury.

A Rare Risky Project for Anime

Adding to this sense of suffocation, Yamada decides to keep almost the entire film set inside the school building. The characters talk about going to a night festival and the beach, but the most we get from these events are pictures being shown between classmates afterwards. With each scene being stuck inside the school, the characters are constantly seen in classrooms and hallways that have large windows looking out towards the sky. The frames of the windows begin to give the illusion of prison bars or, more thematically, a cage.

Intercut within the film is a fairytale story also titled “Liz and the Blue Bird.” This is where the film has some trouble. While it thematically works as an enhanced analogy to Mizore and Nozomi’s relationship, it ultimately feels like nothing more than a narrative element to make sure the audience understands what is happening in the film. To elaborate, there’s an enormous cathartic musical performance between Mizore and Nozomi – delivered with Yamada’s signature camera move to avoid showing her character’s faces – where the two finally hash out their feelings with their music. It’s a strikingly heavy scene, felt by the shivering breath of Nozomi as she plays the flute and the sense of sacrifice being played through Mizore’s oboe.

However, the powerful moment between the two protagonists isn’t really matched by their fairytale counterparts. The fairytale side story ends in a similar way, with Liz and the Blue Bird coming to the same understanding. But in delivery, there’s much lacking to mirror the emotions from the performance Mizore and Nozomi shared. There’s almost a cinematic feeling of disinterest towards the fairytale side story as the film treads on. This isn’t a detriment to the film, but what might come across that way is the expectation that the film will play out in a similar manner as the previous Euphonium works.

An Homage to Arthouse

Liz & the Blue Bird isn’t a typical sequel film to a TV anime; in general, it’s more of an experimental film. Yamada shines in her willingness to take the risk and direct a film for the Euphonium franchise in the manner of an arthouse film. The feeling of imprisonment she creates is anything but comfortable and may even leave a sour taste for those not experienced with watching arthouse, but her desire to test her own abilities outweighs the possible outcome of being misunderstood. Throughout the film, she pays little homages to Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) by Belgian filmmaker Chantel Akerman.

Akerman’s film follows three days in the life of a widowed single mother who finds herself stuck in her apartment all day performing mundane chores, including waiting several minutes for water to boil. In many ways, the three hour long film is a tortuous watch, which makes the final twist in it all the more impactful (it’s become a landmark film among the arthouse circle). While the ultimate theme of Akerman’s voyeuristic film doesn’t transfer to Yamada’s, there is certainly one note taken from Jeanne Dielman: the sense of being caged in the same space for the entire duration of the film.

Even if not many anime watchers have seen or heard about this film, Yamada takes explicit inspiration from it and designs her own film to imprison its audience (all to enhance the empathy between the audience and Mizore & Nozomi). The primary use of indoor settings begins to drown the audience in the sense of claustrophobia a bird might feel when inside a cage; there’s only four scenes where we see characters outdoors, all of which heighten the suffocation felt throughout the rest of the film. However, this isn’t to say that the background art lacks variety. As the film is set throughout the school, there are numerous backgrounds with stellar color designs and density.

A Teenage Story with Mature Flare

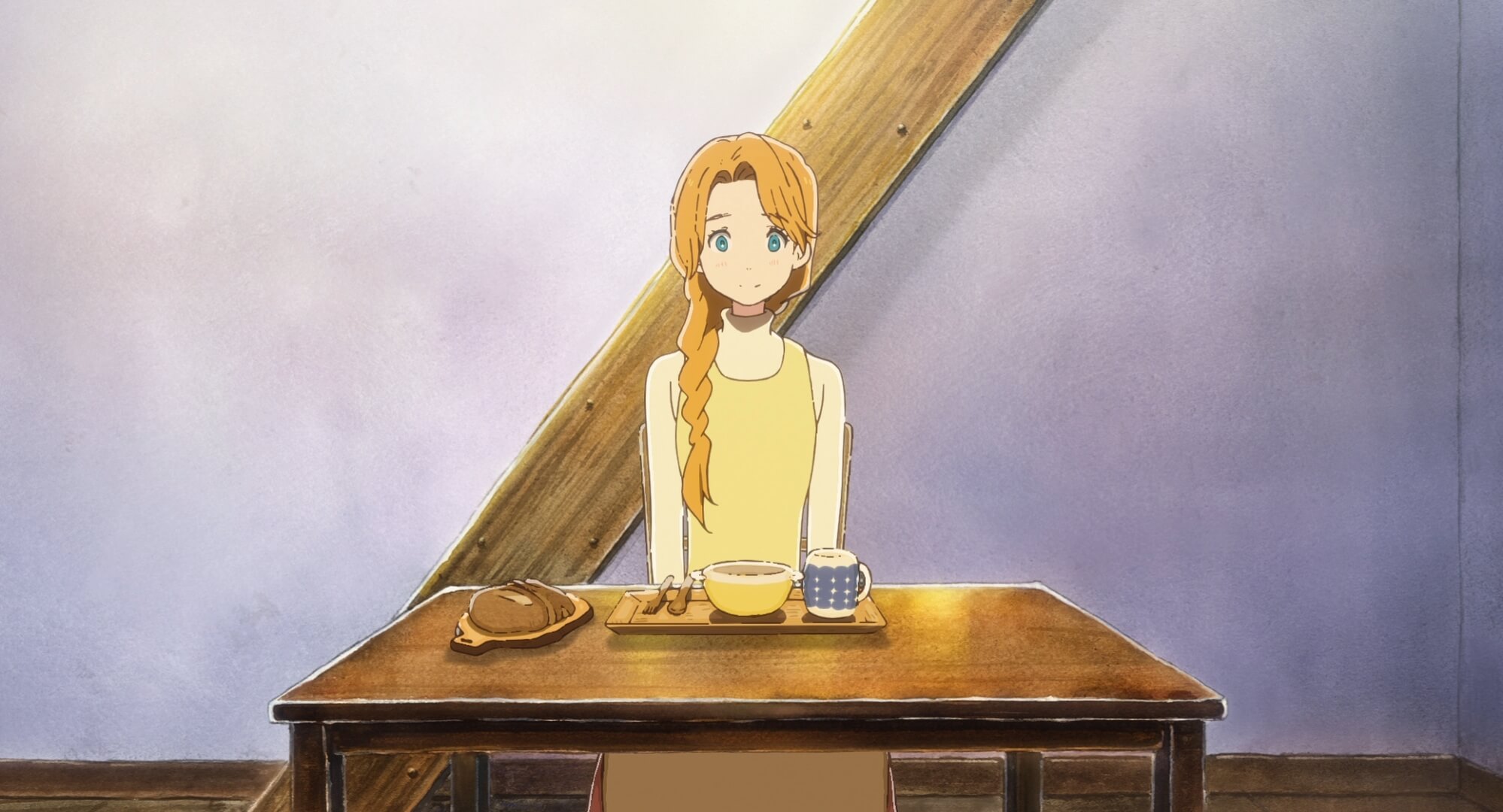

The animation is precise, as expected from Kyoto Animation’s team, with gestures and kinetic characteristics that individualize the two protagonists. Using a visual style that’s very different from the rest of the franchise, the film gets to breathe a unique air, favoring a minimalist quality that draws influence from films such as Ernest & Celestine (2012) and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013). Albeit, with the new minimalistic look, there’s still a weight of realism to the set pieces and character animation.

As for the music, Yamada reunites with composer Kensuke Ushio to develop a score even more experimental than Koe no Katachi’s. Some of the musical personality has returned, with its fragmented piano pieces, but with new pizzazz. The opening five minute track includes all the diegetic sounds from the entire scene that coincides with it. But as the score continues, it hits a territory neither Ushio nor Yamada have explored yet, emphasizing a deafening ambient echo that begins to sit underneath most of the following tracks. As a result, the music becomes haunting and mirrors the film’s visual approach of locking the protagonists in a cage.

Beyond the story, there are many “new elements” that the film offers to the Euphonium universe. Primarily, the highlight of the film leads back to the mature choices – and the effects of those risky decisions – brought from Yamada’s ever growing confident direction. It’s comforting and refreshing to see a mainstream caliber film like Liz & the Blue Bird take the gamble it did. After all, risks don’t always play out for the best, but usually the result from taking a chance ends up being much more powerful than three-quarters of everything else coming out for anime today.

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page