Historically, rock music has been considered an American and British phenomenon, but Japan has had a rock scene for nearly as long as rock has existed. In the 1960’s, the burgeoning Japanese psychedelic rock scene, and a scene known as “Group Sounds,” which fused Japanese popular music with Western rock music and often had English lyrics, were proof of British and American rock’s influence on Japanese music. So, unsurprisingly, when a new crop of Brits and New Yorkers reacted to the big-budget excesses of the 70’s with the abrasive, stripped down sounds and DIY ethos of punk, Japan took notice. But Japan is its own country with its own culture, and politics, and so its punk scene is very much its own thing.

“Its punk scene” is a bit of an oversimplification though. Most countries’ musical landscapes are actually made up of regional sub-scenes, often with surprisingly unique sounds and styles, even between geographically close areas. In the beginning, Japan’s two largest punk scenes were centered around Tokyo and Osaka. The Tokyo scene was the more “normal” one, broadly speaking, with its musical output more closely related to Western punk. The Osaka scene was the “weird” one, and gave birth to noise rock.

The Tokyo Scene

The Tokyo punk scene kicked off in the late 70’s with bands like Friction, who were directly from Tokyo and aped American bands like the New York Dolls and Ramones, and The Stalin, who were from Fukushima but were well known for performances in Tokyo involving gross stunts like vomiting and indecent exposure.

Tokyo punks got their first taste of the widespread notoriety and acclaim that Western bands like The Sex Pistols had achieved with the release of Burst City, a 1982 post-apocalyptic action movie directed by Sogo Ishii.

It starred members of The Stalin as well as The Rockers and The Roosters (two other punk bands), heavily featured their music and performances, and helped cement the early Japanese punk aesthetic in the minds of the public.

Punk rock in Tokyo continued to grow in popularity with the arrival of The Blue Hearts in 1985. Their sound was a touch more melodic and their antics were a bit less confrontational and scatological than earlier bands. As a result, they became increasingly popular, with their final album Pan selling millions of copies.

But even as The Blue Hearts made punk more accessible, there was a darker, more aggressive scene brewing in Tokyo’s underbelly. As early as 1979, the band SS was playing an ultra-fast, stripped down version of punk rock that came to be called hardcore. Some music historians argue that SS actually created the hardcore sub-genre and the bands from California and D.C., who are usually credited with its creation, simply popularized the term. But perhaps the most important Japanese hardcore band was GISM. In addition to pioneering crossover thrash, a sub-genre that injected elements of heavy metal into hardcore punk, their music managed to make its way overseas, where it proved influential to both the metal and punk scenes in America.

The Osaka Scene

As forward thinking as the Tokyo hardcore scene could be, it had nothing on the Osaka scene. Osakan punks borrowed from industrial music, avant-garde, and performance art to create something that could hardly be called music. Here in America, they called it Japanoise. Notable acts include Hijokaidan, a group of guitarists and a vocalist all freely improvising at insane volumes and committing lewd acts, and Merzbow, who helped develop the harsh noise genre, essentially just droning electronic sounds completely devoid of rhythm and melody. Against all odds Merzbow has attained international recognition and continues to work with many artists across the globe.

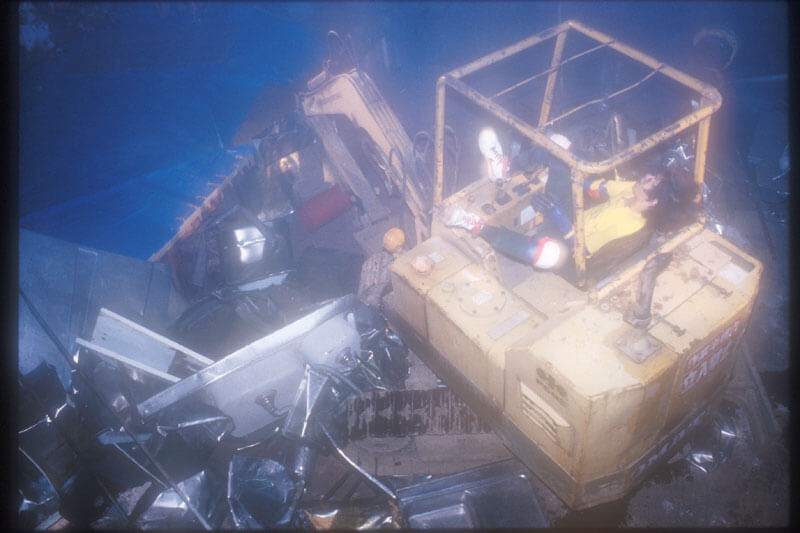

The most recognizable figure in the Osaka scene, however, was Yamantaka Eye. His first band Hanatarash was less a musical act and more a performance art project that made heavy use of sound. Hanatarash’s brand of industrial noise music used actual power tools and heavy machinery in place of instruments. Their live shows were famously dangerous, and attendees would sometimes be made to sign waivers on entry. Eye would do things like strap running circular saws to himself or throw lit Molotov cocktails. He even once drove a bulldozer through the wall of a venue.

After Hanatarash was banned from just about every venue in Japan, Eye founded Boredoms. Boredoms was a pioneering noise rock band that found international success thanks to a friendship with New York noise band Sonic Youth, and to Eye’s work with saxophonist John Zorn’s experimental jazz group Naked City. Boredoms used traditional rock instrumentation with extremely repetitive song structures and droning feedback to craft their uniquely Japanese brand of noise rock, and continue to perform today.

Beyond the Music

Punk rock isn’t just about the music though. It’s a whole subculture, with its own politics, attitudes, and ethos. Punk rock in the West is often staunchly DIY, and it’s no different in Japan. In the early days of the genre, few record labels were willing to take a chance on music that seemed so purposefully obnoxious. This meant bands were forced to finance, record, distribute, and tour all by themselves.

The extreme left-wing views of many punks didn’t make it any easier. Disaffected Japanese youths, particularly LGBTQ people, the poor, and foreign nationals were drawn to the liberal politics and anti-capitalist & anti-government lyrics of punk. In America, record labels were happy to court controversy with these same themes. Rebellion sells in the West, and labels were happy to take advantage. As long as the lyrics didn’t violate FCC obscenity regulations, the punk bands would have no problem getting airplay on MTV and radio.

But in Japan, with its considerably more conservative public, you wouldn’t have a chance in hell. The record industry in Japan heavily self-censors, and will rarely record and never broadcast music that’s critical of the government. And so Japanese punks are all but forced into DIY recording and promotion.

Unsurprisingly, some venues don’t take all that kindly to punk bands either. While there are plenty of live houses, as they’re known in Japan, that do cater to extreme music, the DIY ethos extends to concert locations as well. In the early days of punk, if bands couldn’t find a bar or club that would let them play, they would just play in abandoned buildings, like warehouses or factories. While in America and Europe this led to a vibrant culture of house shows in the suburbs and shows at squats in big cities, Japanese police are far less forgiving of DIY venues. Squats and basement venues are quickly sniffed out and snuffed out.

Yet despite the cop crackdowns and industry resistance, punk rock continued to thrive. The Blue Hearts basically became a national treasure and remain popular to this day. Other bands like Maximum the Hormone, with their blend of J-pop, hardcore punk, and nu-metal, and skate punk band Stance Punks, saw unexpected fame by having their music used in anime. Heavier offshoots of hardcore punk, like beatdown and grind, have enjoyed a surge of visibility and prevalence, if not exactly popularity. Meanwhile, smaller indie labels have cropped up that cater to punks of all stripes and sub-genres.

If you’re interested in learning more about punk rock in Japan, or punk in general, the best way to do that is to immerse yourself. Check out all the bands I’ve mentioned and try to find related artists you like. Find out where your local scene’s bands play and start going to shows. You may be surprised who comes through on tour. I never would have expected a noisegrind band from Tokyo to play a dive bar around the corner from my little apartment in New Hampshire, but they did, and I’d never have known if I hadn’t gotten involved in local music. And if you’re ever in Japan, try getting it straight from the source.

I don’t live in Japan and I won’t pretend to be intimately familiar with the scenes there, but I do have at least a few resources and recommendations for where to start:

- Kaala.jp is an English-language site run mostly by American and Scandinavian ex-pats with a database of extreme bands in Japan and the venues that host them. If you’re ever in Japan and looking for a show, this site could be helpful.

- PIZZA OF DEATH Records is a small label that puts out a lot of pop punk and some heavier stuff like beatdown and metalcore.

- CAFFEINE BOMB Records is another label that focuses mainly on pop punk.

- Photos of Hanatarash’s infamous venue-demolishing performance. Taken by Japanese Punk chronicler Gin Satoh.

- An interview with Gin Satoh.

- More info about the genesis of Japanoise.

- An interview with Nori, a Chinese-Korean punk living in Japan. He discusses the discrimination he’s faced, how he got into punk, and what life as a leftist activist in Japan is like.

- More info about self-censorship (and government censorship) in the Japanese recording industry.

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page