If you are at all familiar with Japanese popular culture, you will probably have encountered the term “boys’ love”, or one of its many sister phrases, such as “801”, “shonen-ai”, or perhaps the most commonly used in the west, “yaoi.” The genre stretches beyond just manga, as it also includes media such as anime, live-action movies, CD dramas, games, light novels and doujinshi, all centered around the romantic and sexual relationships of boys who love boys. As a genre, BL is adored by hordes of fans, criticized by others and often parodied in more mainstream media.

For the past few decades, it has however, become a force to be reckoned with. In this article, we will put on our historical goggles, and have a look at where it all started, and maybe a glimpse at where boys’ love (or BL) might be going from here.

Terminology and Origins of Boys’ Love

Before delving into the development of the BL genre, an explanation of the aforementioned terms might be necessary. Generally, the use of these terms today tends to be seen as interchangeable, much due to the overlapping nature and origins. In the west, the term “yaoi” tends to be used by fans as a way of identifying any media or publication with male homosexual content.

Meanwhile, the current use of the term in Japan seems to separate doujinshi from original content and to classify publications that generally focus more on sex than on plot. Incidentally, one of the early circles publishing BL manga coined the term with the humorous meaning of “no climax, no plot, no meaning” (山場なし、落ちなし、意味なし; yamanashi ochinashi, iminashi), in reference to the lack of plot, although any avid reader will know that in most of these stories, there is no lack of a different kind of climaxes.

Another popular joke among fans is that yaoi is really an abbreviation of yatte onegai iikoto, which literally translates to something like “Please do something good to me”, or the more dubious yamete, oshiri ga itai – “Stop it, my ass hurts!”.

In comparison, many, especially in the west, associate the term “shonen ai” with more innocent content, featuring a larger focus on the emotional aspects and the daily lives and struggles of the characters, and less, if at all, on the sexual.

“Boys love” as an expression first came into existence in the 90s, and was used to describe commercial manga and light novels with a focus on male relationships, but gradually also incorporated non-commercial works, such as fanzines and doujinshi. If you go to a reasonably sized bookstore in Japan, especially in districts such as Otome Road, or Nakano Broadway, publications of this kind will likely be grouped in one section, marked with “BL.”

Regardless of which term you prefer in referring to the phenomena of BL, and whether you prefer manga, novels or games, one thing is clear; fan culture is essential to BL, and most of it is run by women.

Girls’ Manga Revolution of the 1970s

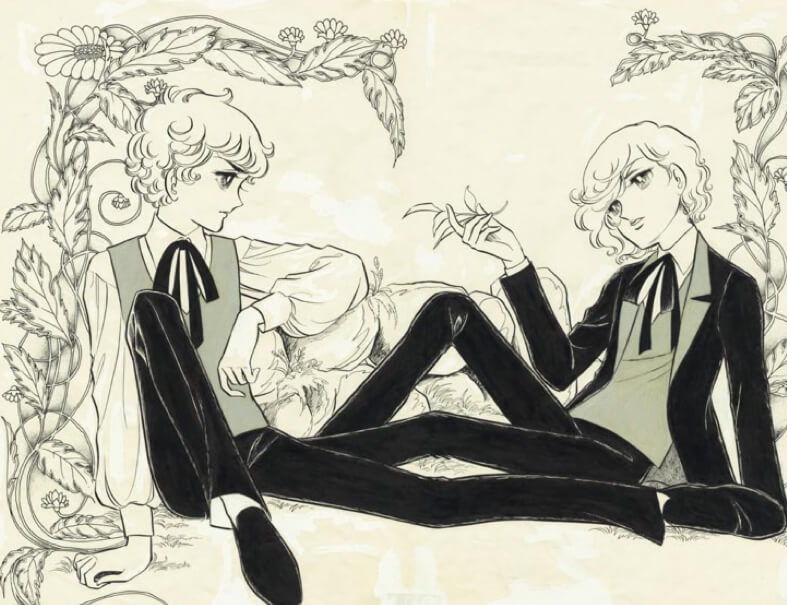

Boys’ love has a history of almost 50 years of development, from its first buds in the 1970s, to today’s international communities and blossoming fandoms. To begin with, it was the so-called “Year 24 Group” (24年組; 24 nen-gumi) that pioneered the genre. This group consisted of several female mangaka who were all born around the 24th year of Showa, or, 1949, who revolutionized the manga business with their stories for young women.

One of the most prominent writers of the era was the now legendary Takemiya Keiko, who challenged both gender norms and sexual boundaries in her works. Notably, her 17-volume series Kaze to ki no uta is considered to be the first BL manga. Due to its explicit content, featuring rape, drug abuse, homosexuality, and homophobia, to mention a few, her publishers originally refused to print the work. Takemiya stood her ground, refusing to censure or change her work. As a result, it took a long nine years from the original conception before Kaze to ki no Uta was finally published in Shoujo Comic magazine in 1976, where it ran to its completion in 1984.

Simultaneously as Takemiya’s love story between Gilbert and Serge unfolded, the magazine JUNE, founded in Japan the late 70s, and its subsequent sister-magazines, had found their foothold in the Japanese market. JUNE is an important stepping stone in BL history, as it combined the tradition of tanbi (耽美), or aesthetic literature, with the shonen-ai of the 70s. Additionally, the magazine often featured more explicit content and was known for its focus on tragic plots and endings. The magazine was so influential, that the word “June“ itself would go on to be associated with, and representative of, BL culture.

By the 1990s, there were four different magazines published under the JUNE name. However, the world of BL had expanded, and what many of us today consider the “classic era of yaoi” was already well on its way. The decade saw the birth of such influential and fabled series as Ai no Kusabi, Gravitation, and Fake, which all eventually saw anime releases. The influential Kaze to ki no uta had been adapted into an OVA as early as 1987, but these new releases and expressions of the genre were far more explicit and distinct in their visuals than the soft, shoujo-esque styles of the Year 24 Group. Additionally, this meant that BL (or shonen-ai) became recognized as a genre of its own, rather than an extension of the shoujo-genre.

International Fame and Internet Culture

Towards the late 90s and early 2000s, the BL phenomena had not only made a name for itself in Japan; it was also catching the interest of audiences abroad.

In its early days during the 70s, BL developed from a form of subculture consisting of parodic or fan-made publications, often seen as the predecessors of today’s doujinshi. These publications featured, much like the doujin of today, couplings of male characters from established series and literature. While this originally was seen as parodies of established works, the circles publishing them often went on to create their own original content under the June movement. I’m drawing attention to this, because it is precisely the culture of doujinshi and fan works that has been instrumental to the explosion of interest in western countries, just as it was important to the development of the genre in itself.

With the increased availability of English translated manga and anime and the accessibility offered by the internet, western audiences were soon exposed to message boards and websites speculating and fantasizing about pairings and character relations. Many had their first meeting with BL through reading doujinshi of popular series such as Inu Yasha or Naruto on the internet, or reading fan fiction. Of course, fan fiction and the concept known as slash was nothing new in western fandoms at this time. For many, however, the introduction to fan-created comics and stories revolving around their favorite characters in romantic and sexual fashion, in turn, led to the discovery of, and interest in, original content BL manga and anime.

With BL now being a force to reckon with, in both western and Japanese culture, it is interesting to see which direction it will head in next. Similar to how the Japanese fan culture helped shape the genre, it now not only shapes new fans, but also new creators. Many published mangaka of the present had their beginnings in small circles creating and publishing doujinshi, for instance. In the West, there has also been an influx of works such as Tea House or Starfighter, by western creators who themselves have been inspired or influenced by BL, despite not necessarily labeling their own works as such. An increase in the interest for male/male content has also lead to some fans starting up their own conventions and creating a market for commercial actors to do the same.

‘By women, for women’?

Traditionally, BL has been presented as being “by women, for women”, but this is also something which has changed in recent times. While the predecessors of today’s BL were generally women, writing for a female audience, this is no longer an uncontested rule.

An associate professor at Oita University, Kazumi Nagaike is one of the critics of the idea that only women read BL. She suggests that the growth in male audiences reading BL has to do with how manga traditionally aimed at a feminine audience presents emotions and feelings in male characters. These portrayals are often hard to come by in more conventional reading material. Some men interviewed in an article for News 24 in 2013 also claimed that it was the homosocial bond between male characters, not the sex, that drew them in. In relation to this, we can look at the way same-sex relationships have become more common in mainstream Japanese media over the last few years.

Additionally, the modern world of BL has acquired its share of male mangaka as well. Although far outnumbered by female creators, male writers, such as Kujou Aoi or Sakura Haiji, are on the rise. Of course, mangaka are an elusive breed, and many choose not to disclose their gender or use pseudonyms so that it is difficult to know just how many male writers of BL are out there. However, 2013 saw the publication of an anthology titled DANSH! by digital bookstore Book Walker. The anthology featured stories of “pure male love”, written by eight male mangaka, including Maekawa Kazuo, who is known for the Ace Attorney series. The aim of the anthology was to portray a different kind of male sensitivity, by authors who normally wrote in other genres, from a male perspective.

New Frontiers

As we can see, BL, while still mostly defined by the roots it developed from, is also taking on new and exciting forms of expression, stepping gradually out of the box. Some of the most popular series of the day, such as Takarai Rihito’s Ten Count, or Nakamura Asumiko’s Doukyuusei series, are challenging the traditional plots (or lack thereof), focusing on slowly building the trust between characters as they overcome the obstacles of their lives, such as mysophobia or uncertainty about growing up and the future. While these are not new themes in BL, it is the way the plot unfolds, with the love and desire developing more naturally alongside the storyline that is intriguing for these modern series.

Lately, there has also been a development in mainstream manga and anime as well, where same-sex couples are becoming more visible. Series such as No.6, Shinsekai Yori and more recently Yuri on Ice have introduced homosexual themes between male characters in a subtle and natural way, not making it the main focus of the plot or character development. Related to this is the 2015 installment to the Gundam series; Mobile Suit Gundam Iron-Blooded Orphans, which featured the series’ first confirmed gay character; Yamagi Gilmerton, a progressive addition to an iconic franchise.

While fandom will often grasp at anything with male/male content to claim it as BL, the lines are gradually getting more blurred in terms of what we can term mainstream and BL. The genre itself, of course, continues to exist within its own framework. It will be interesting to see where it grows from here, and which stories and sub-genres we might be seeing in the future.

Sources: Otakumode, Japancrush, Bookwalker, McLelland et al: Boys Love Manga and beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan (book)

NEW RESOURCE: We are now putting out a monthly list of BL / Yaoi Manga, Manhwa, Manhua, Danmei, & Light Novel Releases in Print!

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page