Most manga in English is distributed by giant publishers such as VIZ Media and Kodansha. But a handful of smaller presses have also carved out a place for themselves in the industry. They have more in common with tiny boutique publishers like PEOW than the manga giants, or even established names like Fantagraphics.

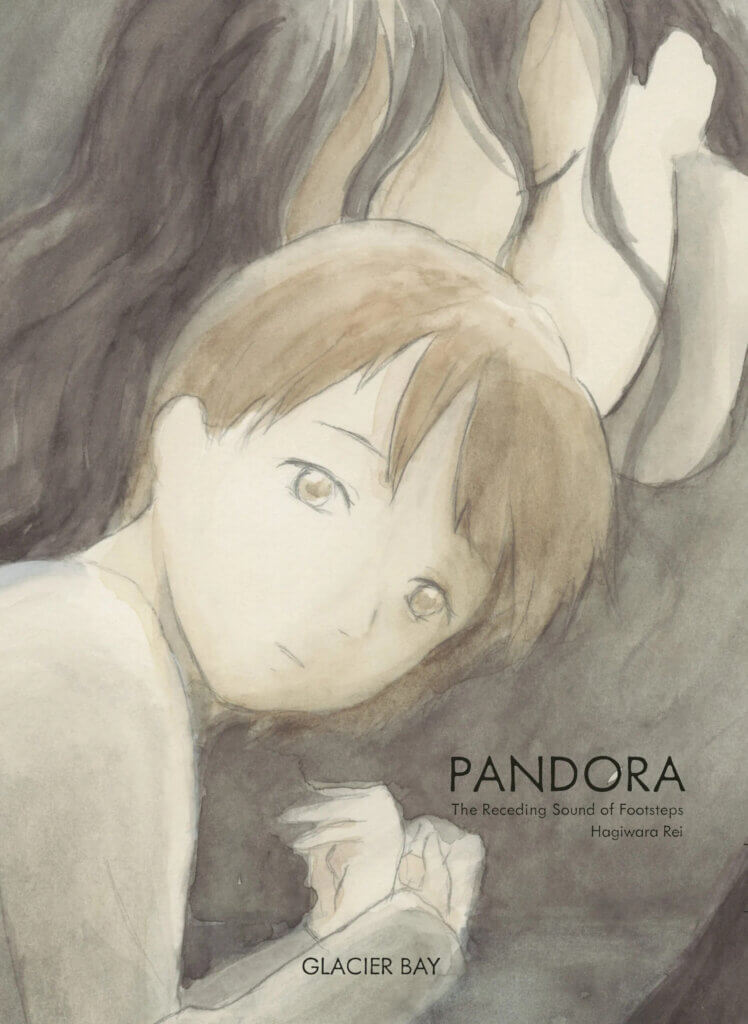

Glacier Bay has made a name for itself among these small publishers. Partly because they publish comics like Imai Arata’s F, an unusual and obscure book even in Japan. But also because their titles, such as their anthology series Glaeolia, have won awards and press attention. Just this year, Kusahara Umi’s Mothers was nominated in the very first American Manga Awards. Its critical success abroad won the author a publication deal in Japan.

Yatta-Tachi was fortunate to have the opportunity to interview Emuh Ruh, who runs the company with the help of part-time staff. They provided us with characteristically thoughtful and detailed responses to existential questions, such as: how do you run a publishing company with so few people? How are these books designed and printed, either in print or digitally? And why did it take so long for a beloved manga artist like Natsujikei Miyazaki to be published in English?

Making Manga

ADAM WESCOTT: How did Glacier Bay Books first get started? Did you have previous publishing experience?

EMUH RUH: Glacier Bay Books started very quietly late 2019, when we published the Sleepy Child comic by Shinnosuke Saika as a small booklet in November. Then in 2020 we had our first major release publishing Glaeolia (volume 1). I didn’t have any previous professional publishing experience up to that point. Although, I started to work with zhuchka and Tim Sun for production on Glaeolia 1 in 2020 and they both already had some experience working with smaller manga publishers. We’ve (I’ve) put in a lot of work and learnt a lot in the intervening years, and it’s fair to say we’ve leveled up our technical skills and capacity from 2019 to now.

WESCOTT: How do the independent artists published by Glacier Bay Books differ from those artists typically published by popular manga magazines in Japan, like Shonen Jump or Weekly Young Magazine? Is there ever any crossover?

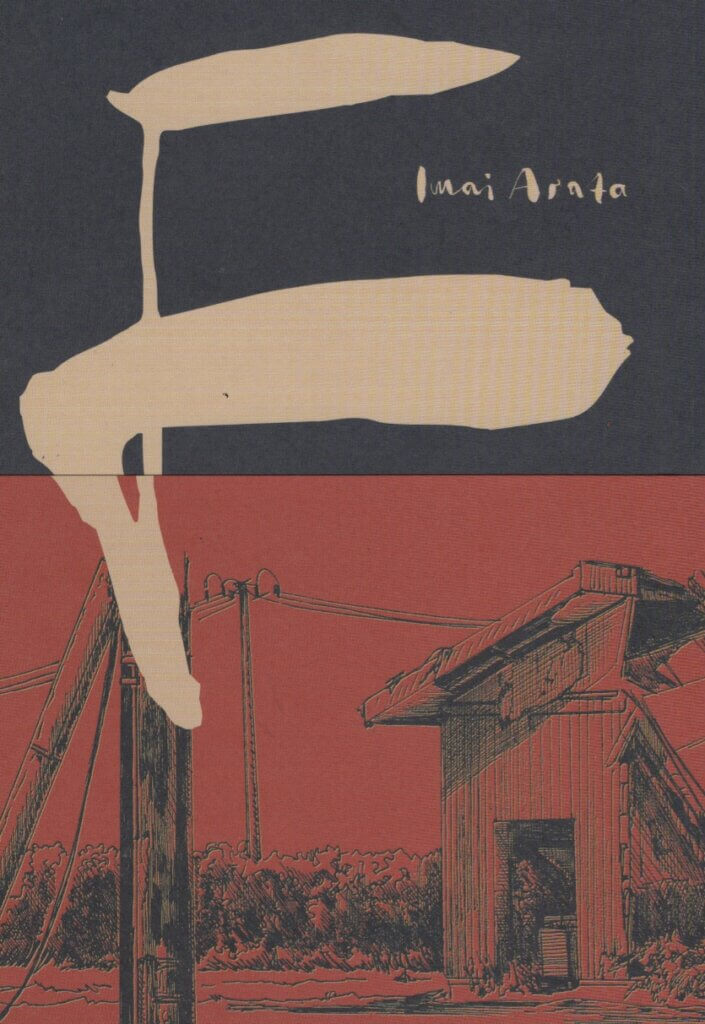

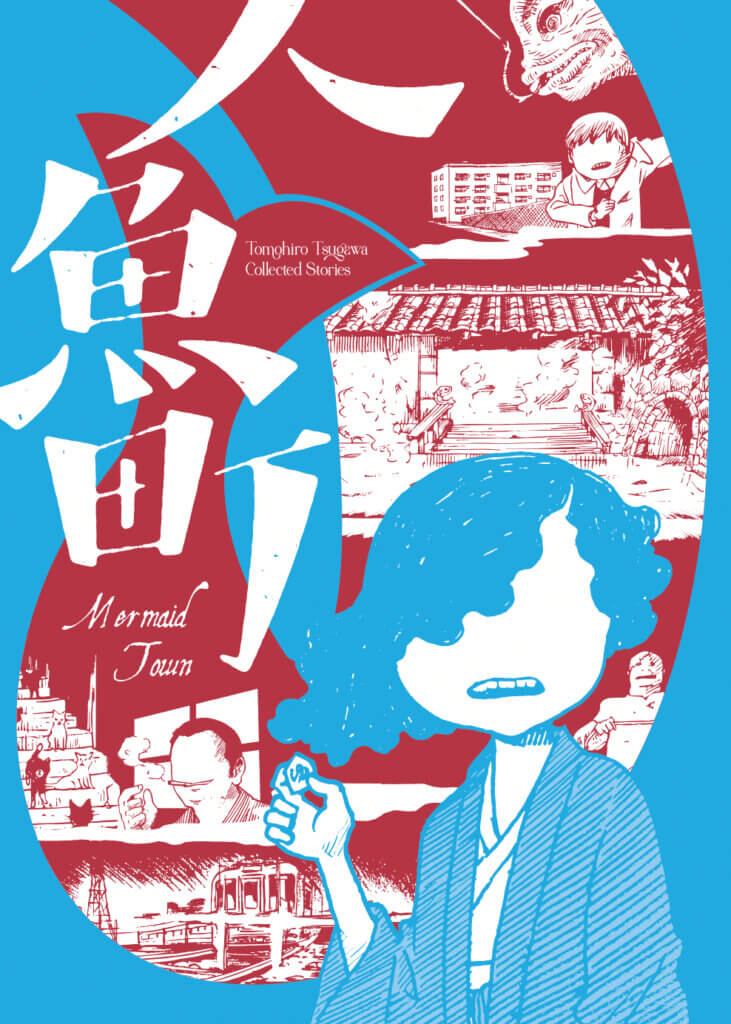

RUH: A lot of the artists we publish are creating manga, but not necessarily in a professional capacity. They may have other careers as artists, or even entirely unrelated work, which they do as their day job. Or they may have hybrid careers, or work professionally, but also self publish on the side. For example, Mitsuhashi Kotaro (The Karman Line author) works as a professional book designer now. MISSISSIPPI is an artist who is active as an illustrator. He’s done book cover illustration, fine art, self-published art books and zines, and published illustrated children’s books with some small Japanese publishers. In addition to this, he continues to put out small zines serializing new stories. Imai Arata has a professional career unrelated to his comics work, and creates art pieces including comics on the side, self-publishing them.

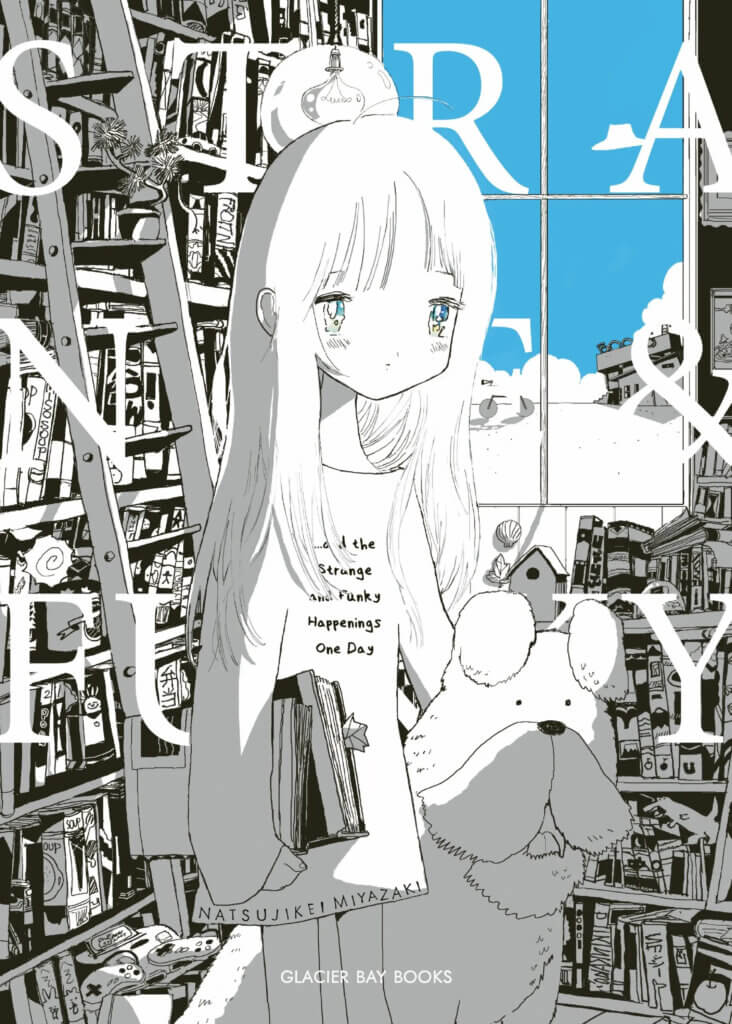

On the other end of the spectrum, we are publishing a collection of sci-fi minicomics from Natsujikei Miyazaki, a professional manga artist whose work is published through major Japanese publishers such as Kodansha and Hayakawa. And then, Sayaka Mogi has had a serialization with Kodansha and put out various series so they are also working as a professional comic artist with Japanese publishers in addition to putting out their own self-published works.

Getting back to the original question, among the artists we work with there is a little crossover, but for most they are independent, and create less commercial works. Even if someone we work with is published in Japan, it’s rarely through a popular shonen manga magazine but maybe in some alternative magazine or another avenue that’s open to less mainstream work. For instance, Mothers by Kusahara Umi was published by us (nom. for ‘Best New Manga’ for the 2024 American Manga Awards!) and then was picked up by Michikusa Comics (TWO VIRGINS publishing house), a small publisher in Japan.

Strange and Funky Happenings

WESCOTT: One of Glacier Bay Books’ upcoming titles I’m most excited for is …And the Strange and Funky Happenings One Day, a collection of stories by Natsujikei Miyazaki. When did you first discover this author, and how did publishing their work via Glacier Bay Books come about?

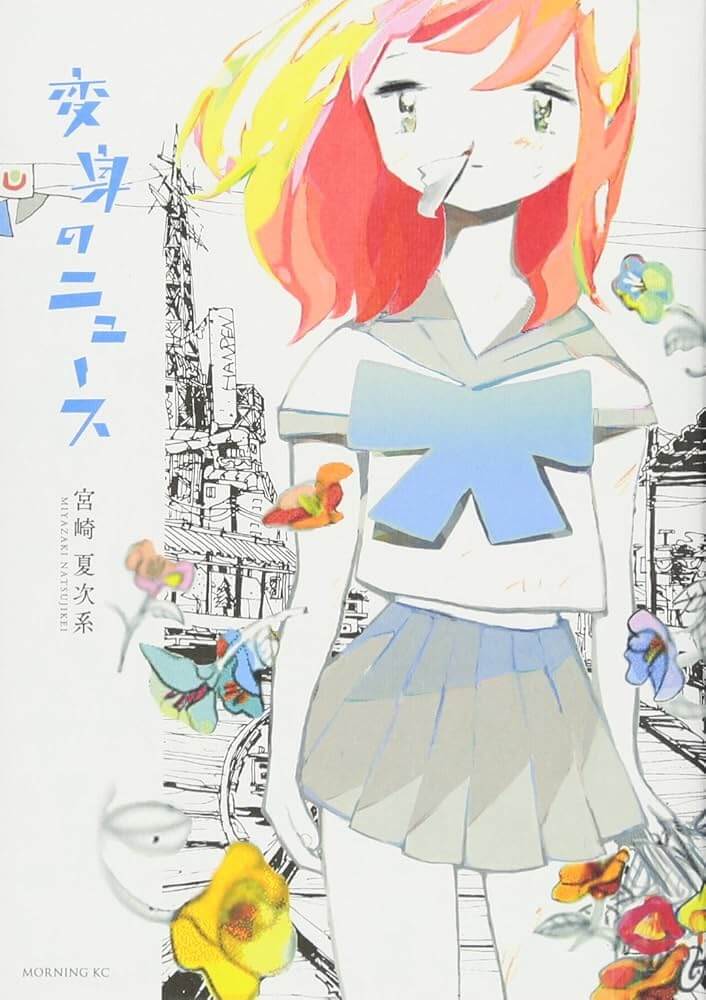

RUH: They’ve been creating comics for a while now. Natsujikei Miyazaki debuted in 2010, through Kodansha I believe. I first became aware of their work a couple of years later after some of their tankobon short story compilations had been released, such as Henshin no News (変身のニュース). After we started working on the concept for Glaeolia, I thought they would be perfect for it, and, as my Glaeolia co editor zhuchka is also a huge fan of Natsujikei’s work, they agreed 100%. This was several years ago now, so apologies if some of the details are a little fuzzy. At this point in time, the only Natsujikei Miyazaki piece released in English was a translation of a short story in the USCA English compilation.

I tried to get in contact with the author for quite a while with no luck. Eventually I was able to get in touch with their editor at Kodansha to request if they would be interested in contributing an existing story to Glaeolia. The editor said that they were too busy [then], but maybe in the future. What you have to realize is that the entire process to get to the point of rejection took many months on and off of navigation and negotiation, and at that point the book was moving far along. So, we shelved it until later. When Glaeolia 2 rolled around, I contacted them again about the possibility, and was summarily rejected. It was the same story for Glaeolia 3. So I’d pretty much given up on being able to do anything with their work through that avenue.

In the meantime I was trying to reach out through other channels such as a doujin magazine they had participated in (already shuttered, and the editor no longer replied to emails), or the editor for a series at a different magazine (I got in touch, however it turned out the editor was only working with the publisher in a freelance capacity and wasn’t able to assist). So in the end it seemed like there was no hope to be had…

Taking a chance

RUH: Months later, I was suddenly able to get in contact with an individual at Hayakawa Shobo who then connected me to Natsujikei’s Hayakawa editor and their licensing division. Hayakawa is a huge Japanese publisher specializing in general literature and sci-fi, big enough that they run their own internal licensing department. They were more receptive to discussions around licensing Natsujikei’s work, and the conversation shifted from including a story in Glaeolia (which was stalled in between issues) to putting out the English edition of their Hayakawa SF short story collection (…And the Strange and Funky Happenings One Day).

I don’t know that I can go into too much detail regarding the actual licensing negotiations. But I can say that it was very interesting insofar as they are a large publisher with certain expectations about the commercial realizations for their publications. Their Natsujikei book in Japan has gone through five printings and they view it as a successful title, so perhaps they are “taking a chance” with us. We are a much smaller publisher, and come from a perspective of working on more non-commercially oriented titles which are lucky to get reprinted or even sell out their initial run.

In my opinion, it highlights the disconnect between the comics markets in the United States and Japan. A work like Natsujikei’s is successful there and recognized as a masterpiece. But, to my knowledge it hasn’t even been considered for publication in the English markets by major publishers.

Flash Point

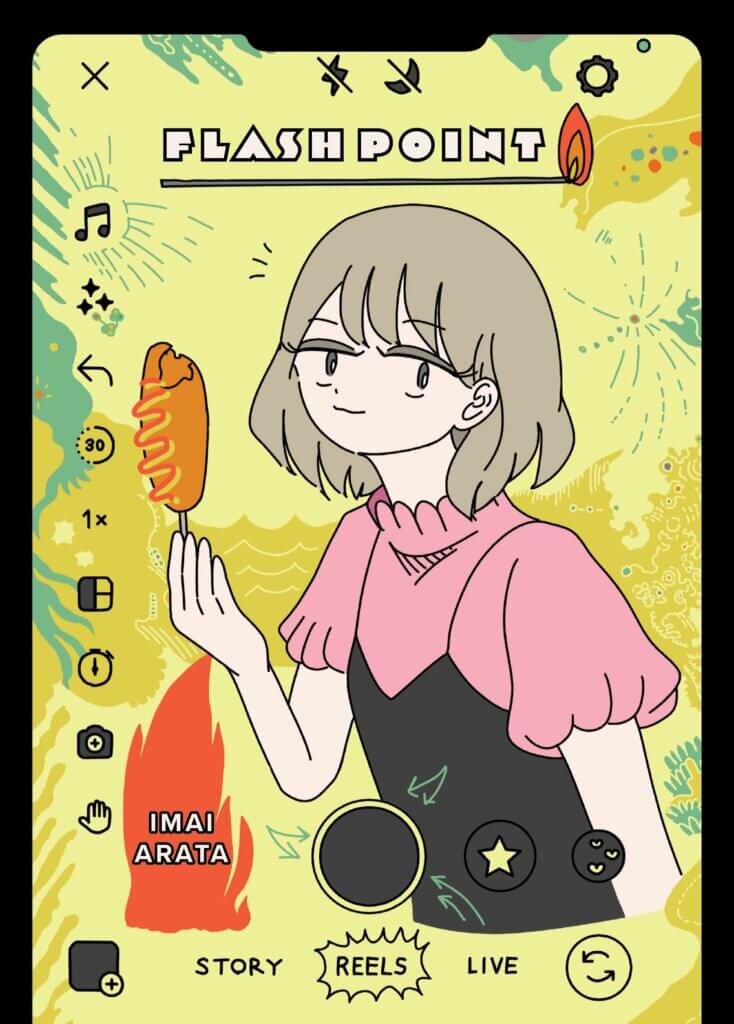

WESCOTT: Another exciting upcoming title is Flash Point, a new work by F‘s Imai Arata. How did the production of this work differ from F, which was originally (according to its explanatory notes) distributed via an art installation? What should readers expect?

RUH: Well, like you said, Imai originally produced F (I am John Cantlie) as part of an outsider art installation with the Chaos*Lounge group. Imai also self published Flash Point, but it was a much more recent release. The production is quite different for Flash Point as he used more digital techniques. So the files were easier to work with in that sense.

For this book, the translator Ryan Holmberg prepared and sent over his translation script. Then we made a rough draft of the lettered English version based on that. There were a couple of rounds of back and forth with Ryan and I checking the current draft and making modifications as needed. When we thought it was polished we sent the final version to Imai for approval. Imai also did an interview with Zach Godin and Ryan, and Ryan translated Imai’s responses and transcribed it to text for the book. I received the text file and prepared the layout for the book, and we checked the text and adjusted it during the editing process.

Like with F, I prepared an original cover design for the English edition. Unlike with F though, this cover design is heavily based on the self-published JP version (which was designed by Imai’s wife). I adapted the front cover for the most part following the original design style of the JP version, but created a new design for the spine, back cover, and french flaps.

I am John Cantlie

RUH: The most enjoyable part was probably creating the design for the back cover. I made a quick mockup that closely followed the JP version to start with, then discussed the target concept for the final design with Ryan. He suggested moving certain rough draft text around, condensing some redundant components, and the general idea for what elements would work for the back cover. From there the final design came together very quickly, and quite nicely in my opinion.

With F, there was a bit more back and forth. I recall that Ryan had one idea for how the cover might look, but I had another. In the end he was pleased enough with the design I proposed that we iterated on that and presented it as the final version to Imai. Also with F, the lettering was not quite as complicated because some of the SFX he used was not quite as laborious to recreate for the English version. But because of how the original was produced, and the files being scans of those penciled hard copies, we had to meticulously remove all of the JP text and do other cleaning and processing to create quality versions for printing.

Flash Point received the 2024 Torch Manga Award’s Enomoto Shunji award; awarded by, and in recognition of, the highly acclaimed mangaka Enomoto Shunji, whose work I do not believe has been published yet in English. Those who enjoyed the gritty political thriller aspects of F will find welcome fare in Flash Point, which foregrounds commentary on fickle viral social media mob violence and conspiracy theories centered around the shocking assassination of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo. It’s got some surprising twists, and a lot of wacky moments and casual daily life humor that I think will resonate with people. There’s a couple underlying plots revolving around the two main characters and the situations that propelled them into the central predicament that are quiet and even sweet at times, and provide some tonal balance to the work overall.

A full time job

WESCOTT: Glacier Bay Books is a very small publishing house even compared to presses like Seven Seas. How do you manage printing and distribution with a limited staff? What challenges do you face? Do you have any advantages compared to a larger publishing house like Seven Seas?

RUH: As far as I know, we are by far the tiniest publisher putting out books at our scale. We are a “1 person” publisher. So safe to say, even smaller than an outfit like Seven Seas. I partner with translators and letterers to create the English translation, but I handle the file prep, layout, design, prepress and print-related work myself. I also do the distribution for the most part, although I do coordinate with other partners to offload some of the work where possible.

Everyone involved in the production team invariably is wearing multiple hats, and in most cases the publishing activity is a side-gig to their day to day work. Even for me running things, it’s been a fluctuation between part time and full time work. Dealing with all of the printing stuff can be a full time job itself, and also takes a lot of time communicating back and forth with printers. But we don’t sell enough for it to be economical to bring on more staff or pay someone else to do that work.

Due to our limited scale, it’s a challenge to put out a quality release for a title period. At this point it’s become almost impossible to get our books into bookstores. There is so much new work coming out and margins are so tight that you just end up getting lost in the noise. In one sense, this is awesome, because everywhere I turn there is cool new work being created. I’m excited for this and look forward to seeing where it goes. But the looming economic downturn and contraction that we’ve been going through, as well as what seems to be a generally contracting “post-pandemic” audience of readers, makes it increasingly difficult to keep making books. I think most small publishers would, at least to some extent, echo this sentiment.

Serious concerns for the future

RUH: It doesn’t help that social media has become worse than ever as a vehicle of communication with readers, an issue from which there’s unfortunately no clear path forward. Even shops that ordered from us regularly back in 2021 and 2022 I don’t hear much from anymore; some of them may even have gone out of business, sadly. Selling books this year on Kickstarter was crucial, as those sales had vanished entirely from our other channels. Without actually checking the figures, I’m confident in saying that we sold more books in one month on Kickstarter this year than in the entirety of 2023. I have tried to open more distribution avenues, including talking to some larger distributors. But those attempts have gone nowhere and it doesn’t seem likely to change anytime soon.

Speaking quite candidly, I have serious concerns for the future. The only option to keep publishing work alive is for new titles going forward to replicate, and hopefully grow, the crowdfunding sales we saw on our recent releases. Personally, I’d rather just sell books through our website and direct to retailers. But at some level you have to go where the audience is. So just to be clear, our disadvantages are constrained revenues, higher operating costs (due in part to a myriad of idiosyncratic issues including the current economic situation), a lack of broader distribution and an overwhelmed retail market limiting our reach.

The power of flexibility

RUH: As for advantages compared to larger publishing houses… we are more “flexible”, in a sense, and it is easier for us to make “arbitrary” publishing decisions. Middle and larger publishers with established distribution channels have to put books on their schedule several months, even years in advance. For Glacier Bay, we are able to just choose to release a book in a month or two and then – presuming we have the capacity to do so – do it. We aren’t beholden to as many moving parts and systems. This freedom is admittedly nice, even if it comes about due to some severe limitations.

After the last Kickstarter was successful I was able to resume previously stalled discussions about publishing some new books. This kind of very quick and responsive flexibility, for better or for worse, is something larger organizations aren’t capable of. Another thing is that we are not trying to be a commercial publisher putting out mass market works with broad appeal. In recognizing the scope and audience for what we want to publish, it frees us to go after more artistic and “niche” works, allowing us to work directly with artists and not be beholden to restrictive sales mandates.

The English market doesn’t buy digital books

WESCOTT: Some of Glacier Bay Books’s titles are distributed digitally via the app Azuki. How did that partnership come about? What do you think about the difference between print and digital comics, or the process of publishing something meant for one medium in another? (I suppose this would include distributing sample comics pages meant for print via social media as well.)

RUH: Back when Azuki was brand new they were reaching out about forming partnerships. I knew one of the people involved with starting it, and was glad a new and seemingly reliable independent company was trying to do something different in the manga space. Because of this, I was already receptive toward them. So I OK’d to add some of our titles which they had requested for their catalog. By that point I already had had some experience with offering both print and digital comics.

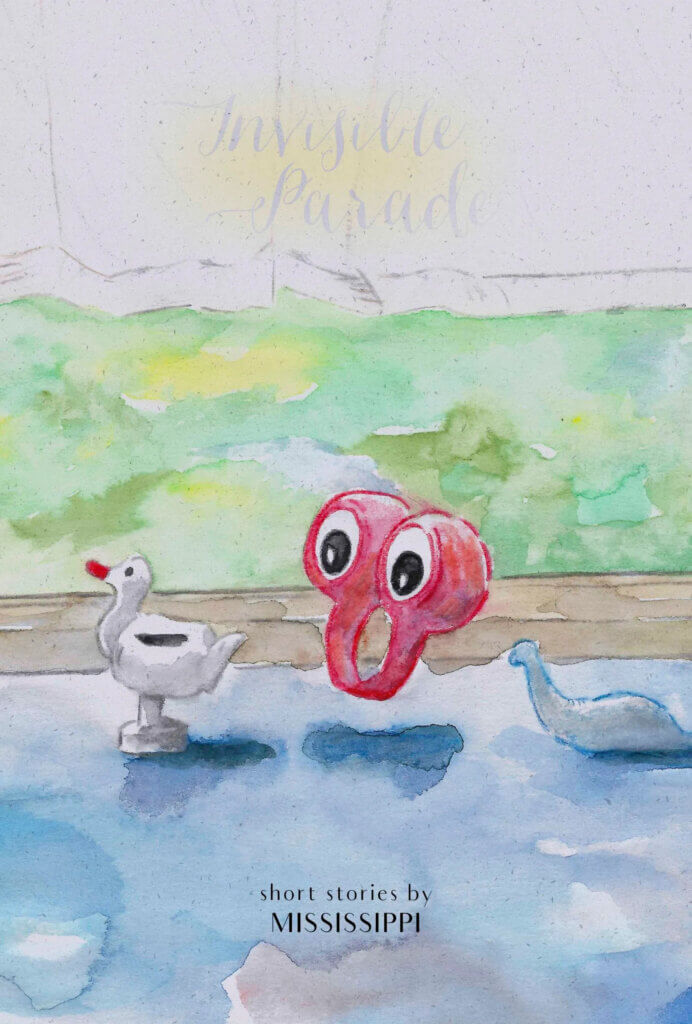

I was originally more optimistic about doing digital, or digital first, comics. We put out Invisible Parade as a digital book first, in the form of the ebook Tsukiko and the Satellite and Other Stories. Anyone who has tried this before will already know where I’m going with this – it doesn’t matter how low you price them, the English comics market doesn’t buy digital books. Maybe you can get a flash in the pan if you’re lucky, and perhaps if you put them out in a larger marketplace, or make them part of a time limited release it might draw some extra eyes, but that’s about it. If you look at the model for Shortbox Comics Fair you can see how this plays out: they concentrate (1) new works through (2) an established venue, and make it (3) a time-limited event. It works out great, but part of that is in eliminating the (small) long tail of a release and trying to concentrate all sales during a limited time release with high exposure.

A fun opportunity

RUH: The Azuki partnership was a fun opportunity. Our indie titles gave them variety early on in differentiating them from the other manga streaming library services that were cropping up at the time, often with larger monied JP publishers behind them. Their platform gave our titles some exposure to a wider audience. But focusing on publishing digital titles is not something I’m in any particular rush to do. The sad truth is that If I published my books digitally and not in print, It’s doubtful in my mind whether any of them would have done more than break even, if that. It’s much cheaper if you don’t have to print the books, but even so you still have to pay people for the work on the books: translation, lettering, layout, design, file work etc. Not to mention paying the authors! So, my opinion about the divide is fundamentally a pragmatic one.

Practically speaking, I work with digital files, I read plenty of comics digitally and purchase digital comics and don’t really see them as lesser things in spite of loving a well-produced print book as a physical object. Reading books digitally can be very convenient, after all. That said, outside of the ability to engineer a set of not-so-easily broadly reproduced special circumstances that drive interest in a digital comic, it’s not really possible to prioritize digital releases. The number of people who purchased and read the last digital-exclusive title I put out can be counted on one hand. So, even though it’s “cheaper” to make, it’s just not a very viable way to publish comics in my perspective.

Publishing media “across” mediums

RUH: Doing digital and print in tandem together works better. But there are restrictions. For instance, I don’t think people understand this, but when licensing a work you have separate licenses for the digital and print releases. Because digital sales are so low (at least for us), it doesn’t make sense to license digital releases for most professionally published titles. If I’m working directly with the artist I usually discuss with them about whether or not we’ll put out a digital edition. There are various concerns involved, and so typically my approach is determining what the author is happy with, and doing that. I do understand that a digital edition is more convenient for readers, so all things being equal I try to also provide a digital release for the handful of people that want it.

As for the process of publishing media “across” mediums, it’s a little more complicated than the layperson may realize. When you think of the digital file for a comics page, there are pixels which light up different values on your screen to show the color (or black and white) regions of the art. But when you look at the file itself, it’s not just telling you which values of RGB color to light up on the screen, it’s also encoding information which tells your computer “how” those values should be displayed (among other things), and adjusts display intent to replicate the same effect on different monitors. And when you convert to and from print you also have to compensate for the qualities of the paper (uncoated / coated, dot gain), as well as splitting up the colors into actual printing ink color channels, and different digital color models. There are even more factors, such as how the art is laid out on the physical page, the bleed and margins to the page edge.

Adapting to print

RUH: So when a file is converted between being made for print or digital release, there are a lot of things happening behind the scenes to adapt between these mediums. This can be a factor if you see art that looks “washed out” online: the artist may have created the art, converted it to a CMYK color profile for printing, and then posted this version (which of course online platforms may treat with their own optimization). The original color information may have been lost or not properly embedded so that it is not rendered correctly on the monitor. Even black and white art can have this issue, since the black ink color channel for printing does not use the full spectrum of digital color information, which makes it appear a little “flat” or desaturated on monitors. I see these kinds of issues a lot with artists who may be less experienced with printing, where they don’t create proper bleed (extra art around the edges to avoid art loss during printing), put text on the margins of the page, use colors that are outside the conventional printing color gamut, and so on.

None of these will necessarily create problems for publishing the works digitally. But the problems adapting to print quickly become apparent. Vice versa, if you have a print adapted or formatted piece like I mentioned, you have to take care that the print specific color policy is adapted to a digital one so that the file is properly represented on people’s monitors. You also have to discard bleed artwork from the final piece, which often includes less polished marks not meant to be seen. I even occasionally encounter these issues with people doing technical file work and have to fix it. (I do some prepress consulting work, so I could be talking about anyone here. Of course I will not mention any names.)

A singular artistic vision

WESCOTT: Glacier Bay Books is just one of many small manga publishers operating right now, a field that includes the likes of Star Fruit Books and Smudge (via Living the Line.) Where do you see Glacier Bay Books fitting in this larger ecosystem? Do you see a commonality with small presses outside manga, like PEOW or Paradise Systems?

RUH: I think the inclusion of Glacier Bay in this field is apt. While there are some commonalities between all of these presses, each brings its own voice. Not to be overly reductive, but you could say that Star Fruit leans into older mainstream manga and indie horror, while Smudge is the Ryan Holmberg-curated horror-gekiga genre imprint. Looking at their recent releases, both seem a little more informed by older commercial publishing practices. PEOW2 with their art-first focus and highly-designed (and diverse in content) books also has a bit of a genre feel with things like their recent EX Mag series, while Paradise Systems still has that handmade feeling due to putting out a smaller number of books at a time, and working directly with individual artists and risograph printing. Each publisher has its own identity to the point that I feel the same “project” from each publisher would come out as a distinguishable release.

Beyond that, even though there are works / artists that many of the publishers in this list would be interested in working on, we all have our own vision for what we want to publish as a whole, what we want to put out into the world. Like how Bulgilhan Press, another great small press publisher, describes their releases as works that fulfill the author’s self-indulgent impulse, are the most “them” book they could create. I often use the phrase “works embodying a ‘singular artistic vision'”, which has its own flavor. But I don’t think it’s that different of an idea.

![The cover of Give Her Back to Me, a book from Glacier Bay Books. Two girls stand together before a simple wood-frame mirror. Behind are sunflowers. The cover is otherwise formatted as if it was a traditional shoujo manga tankobon. [e.g., Hana to Yume https://www.hanayume.com/50th/]](https://yattatachi.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/give-her-back-to-me-738x1024.jpg)

Living in both worlds

RUH: As for where Glacier Bay fits in… I think of us as doing more out there and artistic stuff, from comics artists working in a wide array of styles and practices. But we’re definitely something of a bridge in scope between Para-Sys (smaller print runs) and the Smudge / PEOW level (larger print runs and more established distribution). Another fantastic publisher that I think we are analogous to would be Breakdown Press. I have a ton of love for their books, and respect for what they’ve been able to accomplish. Like Glacier Bay, there’s no one-size fits all approach from them.

Beyond that, a lot of the small press people know each other on a personal level. I’ve been friends with Matt from Star Fruit since before its inception, and talk about publishing stuff regularly with him as well as with folks from the other publishers mentioned. Even though we’re all working on our own stuff and at our own pace, doing as much as can be done, small press publishing isn’t exactly something that’s siloed off. We’re all struggling with many of the same issues, so it’s nice to reach out and consult because usually someone else has been dealing with the same thing. Even as a “manga publisher”, I’m very aware of what’s going on in the broader indie comics scene. I see Glacier Bay’s publishing activity as something living in “both worlds” of manga and indie comics.

Featured Sponsor - JAST

The sweetest romance and the darkest corruption, the biggest titles and the indie darlings; for visual novels and eroge, there's nowhere better.

Big thank you to our supporters

From their continous support, we are able to pay our team for their time and hard work on the site.

We have a Thank-You page dedicated to those who help us continue the work that we’ve been doing.

See our thank you page